Project Gutenberg's Once Upon a Time in Delaware, by Katherine Pyle This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Once Upon a Time in Delaware Author: Katherine Pyle Editor: Emily P. Bissell Illustrator: Ethel Pennewill Brown Release Date: May 16, 2015 [EBook #48976] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ONCE UPON A TIME IN DELAWARE *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Emmy and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

To be Copyrighted

by the Delaware Society of the

Colonial Dames of America

1911

Dear Girls and Boys:

These true stories are written just for you. They tell how once upon a time brave men and women came across the ocean and landed here in the wilderness, among the Indian tribes; how they made farms and towns and cities and formed a state; and how they fought for the freedom and the peace that Delaware now enjoys. Only thirteen out of the forty-eight states of our Union are original colonies, and Delaware is one of these famous thirteen. You are the young citizens, therefore, of an historic state. To you it will fall, some day, to uphold the honor of Delaware. May you be as patriotic and as brave as the Delaware settlers who conquered the wilderness and the Delaware soldiers who laid down their lives for liberty and right.

The Delaware Society of the

Colonial Dames of America.

This book is published by the Delaware Society of the Colonial Dames of America for the use, primarily, of the children of Delaware, in school and out. Its style and matter are therefor chosen to suit young readers.

Many historical points in these stories are more or less disputed. The original sources do not always agree. In preparing these stories of Delaware for children’s reading, it has been thought best to use anecdotes and interesting traditions whenever they could be found. The result is a substantially true set of stories, which do not however, undertake to settle the facts in any disputed case, but are designed to leave in a child’s mind the broad outlines of Delaware history.

The stories have all been read and revised by the Hon. Alexander B. Cooper of New Castle, to whom the thanks of the Colonial Dames are here expressed for his wise and constant help. The Rev. Joseph B. Turner, of Dover, has also kindly read over several of the stories.

| 1— | How Once Upon A Time The Dutch Came To Zwannendael | 2 |

| 2— | How Once Upon A Time The Swedes Built A Fort | 18 |

| 3— | How Once Upon A Time Governor Stuyvesant Had His Way | 32 |

| 4— | How Once Upon A Time William Penn Landed At New Castle | 48 |

| 5— | How Once upon A Time Caesar Rodney Rode For Freedom | 60 |

| 6— | How Once Upon A Time The Row-Galleys Fought The Roebuck | 75 |

| 7— | How Once Upon A Time The Blue Hen’s Chickens Went To War | 84 |

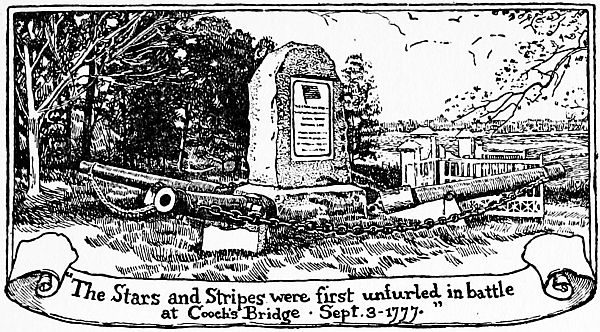

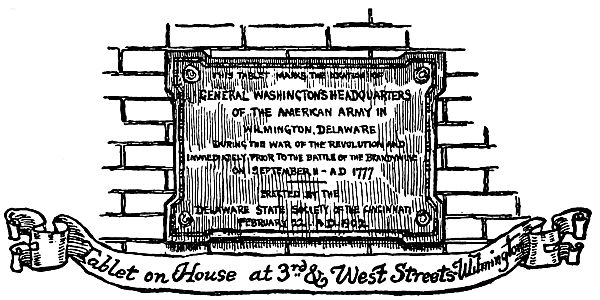

| 8— | How Once Upon A Time Washington Came To Delaware | 100 |

| 9— | How Once Upon A Time Mary Vining Ruled All Hearts | 112 |

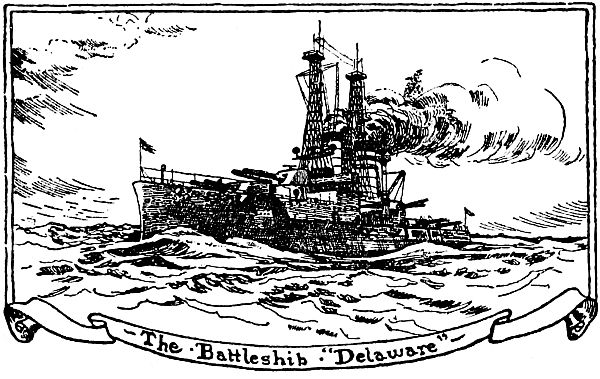

| 10— | How Once Upon A Time McDonough Sailed The Sea | 124 |

| 11— | How Once Upon A Time Delaware Welcomed Lafayette | 138 |

| 12— | How Once Upon A Time Mason and Dixon Ran A Boundary | 152 |

IT was a clear warm day in May in the year 1631, and the sunlight shone pleasantly on a little Indian village of the Leni Lenapes on the banks of the broad Delaware river.

From the openings in the tops of the wigwams—openings that answered in place of chimneys—the smoke of the fires rose toward the cloudless May sky. Kettles were suspended over these fires, and from their contents came a savory smell of cooking—of game, of fish, or of a sort of hasty pudding that the squaws make of corn, which they have ground to meal between stones.

A number of the young men had gone off to the forest in search of game, or had paddled away in their canoes to distant fishing grounds, but some of them were still left in the village. Now and then a brave stalked with grave dignity among the wigwams; and the three chiefs, Quescacous, Entquet, and Siconesius sat a[6] little withdrawn, and in the shadow of some trees, smoking together.

An Indian youth who was setting a trap down by the river paused, when he had finished his task, to look up and down the stream for returning canoes. There was none in sight, but what he did see caught his attention and brought a startled look of wonder to his face. He bent forward in eager attention and gave vent to a low guttural exclamation. Down toward the bay two objects such as he had never seen before moved slowly over the surface of the water. They moved like great birds with wide spread wings; but they were no birds, as the Indian knew well. Whatever they were, they were the work of human hands, and they were coming toward the village.

Once satisfied of this, the Indian turned and sped back to the wigwams to carry the news.

What he had to tell was enough to arouse not only the interest of the younger Indians, but of the braves and the chiefs as well. Soon a group of natives had gathered on the shore, all gazing down toward the bay.

And a marvellous sight it must have been to those Indians that May morning when the two ships of the first colonists who ever settled in Delaware came sailing up the river toward them. In the lead came a vessel of eighteen guns, her sails spread wide to the light breeze, the flag of Holland floating from her masthead. Following her was a smaller yacht named the Walrus. Over the sides of these vessels leaned the sailors[7] and the colonists, blue eyed and fair haired, dressed in cloth suits and glittering buttons.

These immigrants gazed with wonder at the strange natives gathered on the shore—at their painted faces and feathers; and they saw with joy the beauty of this new land. For five months these ships had sailed the trackless ocean, now beaten by storms, now driven on by favoring winds; and now at last, under their leader, DeVries, they had reached their haven.

They were not the first white men who had sailed these waters. Long, long before, Hudson had come this way on his search for a north-east passage to China. In 1612 Hendrickson had ventured up the river in his little ship Restless, but neither of these had set foot on the land, unless it was to seek a spring for water to drink. These men under DeVries in 1631 were the first who ever made an attempt to settle.

Very joyously these first colonists landed in Delaware. Flags were flying and music playing. The cannon of the ship boomed out a salute across the water. It reverberated solemnly over the wild and lonely country where such a sound had never been heard before. The colonists were so delighted with the peace and the beauty of the land that they named the point where the boat first touched, Paradise Point. It is the little projection of land at the mouth of what is now known as Lewes Creek.

The three chiefs, gorgeous in paint and feathers, came down to meet the strangers and conducted them up the shore to the village. Here[8] they motioned to them to seat themselves around the fire and smoke the pipe of peace.

The various small tribes of Indians in Delaware all belonged to the one great tribe of the Leni Lenapes.

DeVries, on his side, was very anxious to establish friendly relations with them. He believed that if the natives were treated fairly and kindly there would be no trouble with them.

We do not know how the bargain was made between the Indians and the white men, whether by signs or whether through an interpreter sent down from the New Netherlands (New York) which had been settled some time before. But we are told in the old documents that this first tract of land, thirty-two miles along the bay and river from Cape Henlopen, was sold by the Indians for “certain parcels of cargoes,” probably kettles, cloth, beads and ornaments.

After the bargain was made, DeVries again took ship; and the three chiefs sailed with him up to New Netherlands, where a solemn deed was made before the three chiefs and signed and sealed by the Dutch Governor and the Directors, Council and Sheriff of the New Netherlands.[1]

Down in the newly purchased land the colonists immediately set about building shelters for themselves. Their possessions had been landed with them—their chests of clothing, their farming tools, and the seeds they had brought from home. They must begin to prepare fields, too; for it was time the seeds were planted.

The spot they selected was near the mouth of the creek, where there was a spring of delicious[9] cool water; and, because of the wild swans that were sometimes seen there, they named their little settlement Zwannendael. The river they called Hoornekill in honor of DeVries, whose native place was Hoorne in Holland.

The natives watched with wonder the strange work of these colonists, and the square houses with doors and windows which they made, and which were so different from the round wigwams woven of boughs and barks.

Beside separate cabins the settlers built themselves a general house to serve as defense in time of need. They called it Fort Uplandt; but DeVries placed such extraordinary confidence in the Indians that the so-called fort was only a house, larger and stronger than the cabins, and surrounded by a high fence.

So diligently did the settlers go about their work that by the middle of the summer they were quite well established.

DeVries was anxious to go back to Holland and bring out more settlers, so he appointed Giles Hosset[2] Director of the colony and then made his preparations to sail.

It was with heavy hearts that the little band of colonists saw the ship that had brought them from home spread its wings and sail away.

They watched it until it was only a speck in the distance, until even the speck had disappeared. Then they turned again to their work with a new feeling of loneliness. They were so few in that great land of savages.

They had provisions enough, brought from home to last them a year and there was some[10] comfort in the fact that the yacht Walrus was left behind. She was anchored just off shore in the river, and from there she could keep guard over the little colony like a mother bird guarding her nest. If danger arose, the settlers could retreat to her. But what danger was there to fear when the Indians seemed so peaceable and friendly?

For some months after DeVries left them, all went well; and then trouble arose. The trouble was over a very little thing, no more nor less than a little square of tin.

One of the first things the colonists had done after settling their farms, was to erect a pillar, and place on it a piece of tin carved with the arms of the United Provinces, as Holland was called. Those arms, set high above the village, were to them a constant reminder of their old home across the sea; and often, as they went to and fro about their work, their homesick eyes would turn to it for comfort.

But one morning when the colonists arose to go to their daily toil, the piece of tin was missing. Evidently, someone had wrenched it from its place in the night.

Angry and excited, the colonists began to make inquiries. For a time they learned nothing of how or why it had been taken, but at length they found it had been stolen by an old chief to make tobacco pipes. Then the colonists were more angry than ever. It seemed an insult to their country that her arms should have been put to such a base use.

The natives were much alarmed when they found how angry the settlers were. They did not understand why they set such value upon the arms. Was the piece of tin something sacred—something that the pale faces worshiped? Out in the river lay the Walrus, seeming to threaten them with its presence; and soon the great sachem DeVries would return, unless they could make their peace with the pale faces.

A few days later some of the natives came to the settlement, bringing a gift to the white men—a gift that they hoped might soothe the anger of the settlers. It was the bloody scalp of the old chief. They had killed him and brought this as a peace offering.

The settlers, with Giles Hosset at their head, were overcome with horror.

“What have you done!” Hosset cried, “Why did you not bring him to the fort? We could have reproved him, and told him that if he did such a thing again he would be punished. But you yourselves should be punished for this. It is a bloody and barbarous act!”

The Indians heard him with sullen look. They in their turn were enraged. They had thought to please the white men by killing the white men’s enemy, and now the white men were more angry than ever. The natives dissembled, however; they went away with calm looks, but black rage was in their hearts.

Giles Hosset was deeply troubled.

“Evil will surely come of this,” he said. “Innocent blood has been shed, and something tells me that more will follow.”

However, the next few days passed peacefully. Giles Hosset’s fears began to die away. The Indians were apparently as friendly as ever, and the whole tragic event seemed to have been forgotten. But it was not. There were friends of the chief who remembered and blamed the pale faces for his death, and whose hearts were full of hatred and revenge.

One morning the little ship Walrus drew up its anchor and sailed down the bay and out into the ocean to look for whales. There were said to be a great many along the coast, and an Indian had brought them news of one that had been spouting outside at dawn.

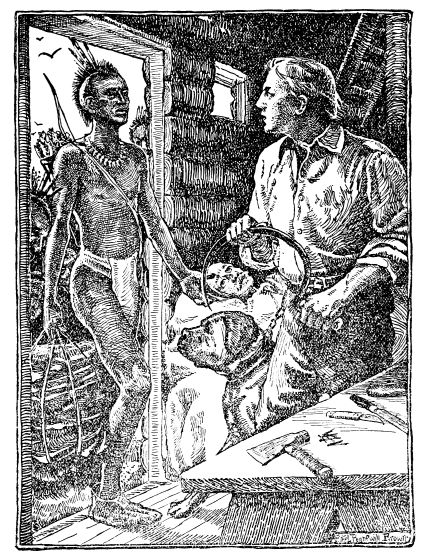

The colonists were gathering in their crops, and the little cluster of cabins lay peaceful and deserted in the golden autumn sunlight. Two people only were left in the strong house. One was a man who was sick and so unable to work; the other was a stout, strong fellow who stayed there on guard. A great brindled mastiff was chained to the wall by a strong staple. He lay asleep, sometimes rousing himself to snap lazily at the flies. The guard was sharpening some farm implements; the man on the bed lay watching him, and now and then they chatted idly.

Suddenly the great mastiff lifted its head and listened. Then it sprang to its feet, struggling against the chain and growling ominously.

“What is it?” asked the sick man.

The guard went to the door and looked out.

“Indians,” he answered.

“Indians?” repeated the sick man, “I like not that they should come here when all the others are away and out of call.”

However, it seemed that these Indians had come on a matter of barter. They had with them a stack of beaver skins, which they wished to exchange for cloth or provisions. They spread them out on the floor, and the white men grew quite interested in examining them.

Presently they made their bargain, and the guard said he would go up to the loft and get certain of the stores that were kept there.

One of the Indians followed him up and stood around as he selected the things he was to exchange for the skins. Then, as the guard started down the ladder, swift as lightning the Indian struck him with an axe he had picked up, and crushed in his head. The man had not even time to cry out.

Immediately, and as though this sound had been the signal, the natives fell upon the sick man and killed him. Others rushed upon the dog, but there they met with such a fierce defense that they fell back. The brave beast pulled and struggled against the chain, and a moment later he fell pierced by a shower of arrows.

When nothing was left alive in the strong house, the Indians went out to where the colonists were quietly at work in the fields, guessing nothing of the tragedy that had just been enacted at the strong house.

The Indians approached them tranquilly, their weapons carefully concealed. So friendly[14] were their looks that the white men felt no fear; but only Giles Hosset, remembering the death of the chief, watched them with some uneasiness. But even he had no faintest suspicion of the bloody work so soon to begin.

When the Indians were quite close to the settlers, their friendly look suddenly turned to one of ferocity and hate. Weapons were flourished, they burst into their terrible war cry and fell upon the defenseless colonists. So thorough was their work that, when it was ended, not one white man was left alive to tell the tale of the terrible massacre of Zwannendael.

Meanwhile, out in the ocean, the Walrus had cruised about all day; but the sailors had seen no signs of the whales the Indians had told of and at evening they came sailing home.

What was their surprise, as they approached the settlement, to see no signs of life. They could not understand it. Only when they reached the strong house and saw the bodies of the men and the dog, did they begin to guess at the terrible tragedy of that day.

They hastened to the field where they had left their friends cheerfully at work that morning. Not one was left alive.

Filled with despair, the survivors hurried back to their ship. The native village too, was empty, the Indians had disappeared; but the white men were afraid to stay on the shore. They spent the night on the Walrus, and the next day set sail for Holland to carry the sad news to DeVries.

We are told that DeVries had almost finished his preparations and was expecting soon to return to Zwannendael, but that when he heard the tidings he was overcome.

The return voyage was given up, for the new colonists were afraid to risk the fate of the others. And so, in the massacre of Zwannendael, ended the first settlement ever made on Delaware soil.

Yet still the land had been possessed by the Dutch. It was not, any more, unclaimed land that belonged to any man that came along. When the King of England gave away all the land along that part of the coast to Lord Baltimore, only three years later, he could not give this land of Delaware, because it had already been settled by DeVries for Holland. Our state began when the Dutch colonists first stepped ashore on Paradise Point.

[1] Bancroft says, “The voyage of DeVries was the cradling of a state, and that Delaware exists as a separate commonwealth is due to the colony he brought and planted on her shore. Though the colony was swept out of existence soon after, this charter, three years before the Maryland patent was granted Lord Baltimore, preserved Delaware.”

[2] Giles Hosset in this position as Director of the Colony may well be called the first Governor of Delaware.

SPRING had come again. The sun shone as bright and clear as when, seven years before, DeVries and his Dutch settlers had sailed up the Delaware and landed on its shores.

That was in 1631. Now it was the year 1638, and two other vessels[1] were sailing up the broad river. But these ships were not Dutch; they carried the colors of Sweden, and the men who crowded to the sides of the vessels to gaze at the unknown shores were Swedes.

Six months before, these men, fifty in all, had started out from Gottenburg to journey across the sea to this new land. For six months they had been tossed and beaten by many storms upon the ocean, but now at last they had reached the promised land.

Slowly they sailed up the river and past the mouth of the Hoornekill.[2] The colonists stared in silence at the spot where the little settlement of Zwannendael had once stood. Nothing marked the place now but a few blackened ruins; and these, wind and storm were slowly eating away.

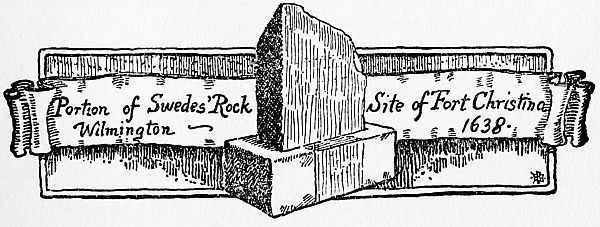

The Swedes did not stop there, but sailed on up the river. Their commander, Peter Minuit, had once been with the West India Company at New Netherlands, and knew something of the country and had a clear idea of where he wished to start his colony. Some miles above the Hoornekill, Minquas Creek (now our Christiana) emptied into the Delaware. Two and a half miles from its mouth, a point of rocks[3] jutted out into the stream and made a sort of natural wharf. It was upon this point that the Swedes made their landing.

Stores and implements were carried to the shore, and soon the silence of the new land was broken by the sound of the ax and the voices of the settlers talking and calling to one another.

Lonely and deserted as the country had seemed to the new settlers, their coming was quickly known to both the Indians and the Dutch.

The first to visit them was an Indian Chief named Mattahoon. He and some of his braves stalked in among the colonists one day, with silent Indian tread, and stood looking about them with curious, glittering black eyes. Minuit gave them some presents, and they seemed much pleased. Then Mattahoon told Minuit[23] that the land belonged to him and his braves.

Minuit wished to buy it from him, and the Sachem agreed to sell it for a copper kettle and some other small articles. These were given to him, and he and his braves went away, well content with their bargain.

The next visitor to come to them was a messenger from New Amsterdam. He told them that Director General Kieft, the Dutch Governor, had sent him to ask why they had settled on land that belonged to the Dutch. The Dutch had bought it from the Indians long ago, at the time DeVries had settled on the river.

Minuit answered the messenger very civilly. He gave the Dutchman to understand that he and his Swedes were on their way to the West Indies, and had only landed on this shore for rest and refreshment.

The messenger believed what Minuit said, and was quite satisfied, and the next day he returned to New Amsterdam and told Kieft there was nothing to fear from these strangers; they were only passers-by and had no wish to settle upon the river.

However, not long after this, a Dutch ship sailing up the river saw that the strangers were still there. Moreover, they were building houses and something that looked like a fort, and gardens were laid out.

Kieft, the Dutch Governor was very angry when he heard this. Again he sent a messenger in haste, to ask why the Swedes were building, and to demand that they should re-enter their ships and sail away.

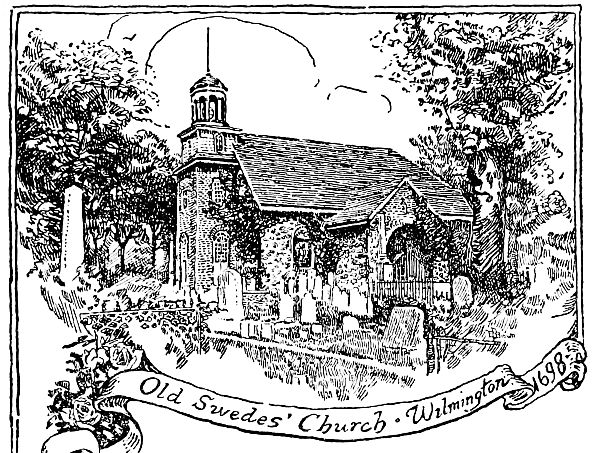

Minuit paid but little attention to this second messenger. He was very busy. The fort was almost finished. Reorus Torkillus, a clergyman who had come from Sweden with him, had already held services in it, and had prayed for the welfare of their little settlement of Christinaham, for that was what they had named it. The fort itself was called Fort Christina, in honor of the Swedish Queen, and the name of the creek was changed from Minquas to Christina.

It was of no use for the Dutch to send messengers now. The Swedes were well established. Moreover, they had made friends with the Indians. Minuit had given them a number of presents—kettles, cloth, trinkets, and even fire-arms and ammunition.[4]

With these presents the savages were delighted; and they signed a paper with their marks, giving to the Swedes all the land from Cape Henlopen to Santican, or what is now called the Falls of Trenton. When the Dutch heard this, they were indignant for they claimed that all that land had already been sold to them.

Reorus Torkillus, the Swedish minister for the little settlement, did what he could to keep peace with both the Dutch and the Indians. He was an earnest, pious man, and his great hope was that he might convert the savages to Christianity. He regularly held Divine service in the fort. He also had a plot of ground fenced off to serve as a burying ground when such might be needed.[5]

The Indians understood but little of the teachings of Torkillus; but there was one thing that[25] they did understand, and that was that the Swedes gave them many presents and paid them better for their furs and skins than the Dutch did. Minuit, indeed, was always careful to find out what the Dutch were paying them and then to offer a little more. In this way he secured all the best and choicest of the furs—a cause of fresh anger to the Dutch.

But with all this friendly feeling between the Swedes and the Indians, the settlers were obliged to be on their watch with the savages. The Leni Lenapes, to which the Delaware tribes belonged, were for the most part a peaceful people; but there often appeared among them Indians from another tribe, probably Iroquois, whom the settlers called “Flatheads.”[6] These strange Indians were both cruel and treacherous, and they made it dangerous for a settler to venture out of sight or hearing of the settlement. Often they would hide in the woods and fall upon some lonely wanderer, and kill or stun and then scalp him.

The scalping itself was not always fatal. There is a story of a drunken soldier who fell asleep across his gun. When he awoke, he had a strange feeling in his head. At first he thought it was the effect of what he had drunk, but presently, to his terror, he found he had been scalped. And there is a story too, of a woman who had gone into the forest to gather fire-wood. She was struck down, stunned, and scalped by a Flathead, but she lived many years afterward. Her hair, however, never grew out again, except as a fine down.

There was another thing about the Indians that, as time went on, made the settlers more and more anxious. In order to keep them in good temper, it was necessary to continue to give them presents. At first it was easy for the colonists to do this, for they had brought with them from Sweden a large store of things for that very purpose. But as time went on, their stores dwindled away. They had expected ships from home to bring them a fresh supply, but no ships came.

Week after week and month after month passed by; the home land seemed to have forgotten them. Their cloth was all gone, their clothes were threadbare, and many of their cattle had died. The Indians came to Christinaham, expecting presents, and went away with angry looks and empty hands.

In the year 1640 the Chief Mattahoon called together a great meeting of the sachems and warriors of Delaware. The meeting was held deep in the wood where no white man could come. All the chiefs and braves were gathered there, old and young. They ate and drank. Then Mattahoon spoke to them. He asked them whether it would not be better to kill all the Swedes. He said:

“The Swedes live here upon our land, they have many forts and houses, but they have no goods to sell us. We find nothing in their stores that we want. They have no cloth, red, blue, or brown. They have no kettles, no brass, no lead, no guns, no powder. But the English and[27] the Dutch have many things. Shall we kill all the Swedes or suffer them to remain?”[7]

An Indian warrior answered:

“Why should we kill all the Swedes? They are in friendship with us. We have no complaint to make of them. Presently they will bring here a large ship full of all sorts of good things.”

With this speech all the others agreed. Then Mattahoon said:

“Then we native Indians will love the Swedes, and the Swedes shall be our good friends. We and the Swedes and Dutch shall always trade with each other.”

Soon after this the meeting was dissolved, and all the Indians returned to their own villages.

The Swedish settlers knew nothing of this meeting, but they had felt that they were in danger. It was in March of that year, 1640, that they decided, with sad hearts, to give up their little settlement and remove to New Amsterdam. Preparations were made for abandoning Christinaham. Tools and provisions were packed, and the boats made ready.

The Dutch heard with joy that the little settlement was to be given up. At last they would be rid of their troublesome neighbors.

However, the very day before the Swedes were to leave, a vessel arrived from Sweden, bringing them cattle, seeds, cloths and all the things of which they were so in need. The ship also brought a letter from the wise Swedish Councillor Oxenstiern and his brother. In this letter, the colonists were encouraged in their undertaking[28] and told to keep brave hearts. They were also promised that two more vessels should be sent out to them in the spring.

When the colonists heard this news, they shouted for joy. The household goods which they had packed with such heavy hearts were now unpacked, the houses were opened, and the work of the village was taken up again.

The Indians were greatly pleased. Now they saw how wise they had been to have patience and wait, instead of killing all the Swedes as they had been tempted to do. The Swedes were again their best friends, and the givers of many gifts.

The Dutch were obliged to swallow their disappointment as best they could, for now the Swedes were more firmly settled than ever. Fields were tilled, and orchards planted. Later on they built forts at the mouths of various Creeks, so as to prevent the Dutch from trading with the Indians.

When, in 1643, Lieutenant Printz came out from Sweden to take the position of Governor; he built a handsome house on Tinnicum Island, just above Chester, and also a fort and a church.[8] The principal Swedes built their houses around this fort, and the village that arose back of it was called “Printzdorf.” Thus the capital of New Sweden was removed from Christinaham to Tinnicum Island.

The Governor held absolute power over the little colony, and all matters were decided by him according to his own will.

There were, at this time, two kinds of people upon the Delaware; the freemen, who owned[29] their own land and farmed and traded, and prisoners, who had been sent over from Sweden on the earliest vessels, and who were employed in digging ditches and hewing and building, and were treated as slaves. In fact, there was no lack of laborers in the colony.

Rich cargoes of furs and tobacco were now sent back to Sweden. The Dutch were in despair. They saw all the Indian trade being taken out of their hands; but Sweden was too powerful both at home and abroad for them to dare to interfere with her, and from this time until Stuyvesant came out to be Governor of the New Netherlands the Swedes ruled supreme along the Delaware.

The spot where the Swedes first landed is still preserved, and is marked by a portion of the original rock, placed close to the landing-place on the bank of the Christiana. This rock bears an inscription, and is enclosed by a low iron railing. It may be called the Plymouth Rock of Delaware, for it is taken from the natural wharf of rocks on which the Swedes first stepped, and marks the first permanent settlement made in Delaware.

[1] The ships were the Key of Kalmar and the Bird Grip or Griffin.

[2] A landing was made a few miles above the Hoornekill at a point between the Murderkill and Mispillion Creeks, in Kent County, but the Swedes only stopped there for a short time for rest and refreshment. The place was so beautiful that they named it Paradise Point.

[3] This point of rocks marked the foot of what is now Sixth Street, in Wilmington.

[4] Giving or trading fire-arms or ammunition to the Indians was afterward forbidden on pain of death. The arming of the Indians was considered too dangerous.

[5] Upon the site of this burying ground the Old Swedes Church now stands; and somewhere beneath it lie the bones of Reorus Torkillus.

[6] So called from a curious flattening of the crown of the head.

[7] This account is given by Campanius.

[8] The present church of Old Swedes at Wilmington, was not built until 1698, so this church on Tinnicum Island was the first one built by the Swedes. In Minuit’s time, Torkillus had held Divine service in the fort.

PETER STUYVESANT was a tall, red-faced Dutchman who came out to the New Netherlands in 1647, to take the place of Kieft as Governor of that Province.

Governor Stuyvesant had fought in many battles, and in one of them had lost a leg. When he came out to New Netherlands he had a wooden leg; and as it was fastened together by rings of silver, it was often called “the Governor’s silver leg.” Stuyvesant had also a very violent temper; and, when he was angry, he stamped about with this leg as though it were a club and he were beating the floor with it.

At this time, in 1647, the Swedes claimed all of Delaware as theirs, and called it New Sweden. They had driven many of the Dutch away, had torn down their buildings, and had kept them from trading with the Indians. Every little while news of fresh wrongs to the Dutch was brought from Delaware to Governor Stuyvesant; and every time a letter or messenger arrived, the Governor had a fresh fit of rage. He believed that the Dutch were the real owners of the river; and, if he could, he would have gathered his soldiers together and sailed down to New[36] Sweden, and have done his best to drive every Swede out of the country.

This he could not do, however; for the Directors of the West India Company, who had given him his position as Governor, had told him to keep peace not only with the Indians, but with the Swedes as well.

This was a hard thing for a hot-tempered man like Stuyvesant to do. Now the story would be that the Swedes had destroyed more of the Dutch buildings along the Delaware; again, that the Swedes had incited the Indians to try to surprise and massacre the Dutch; and Hudde, the Dutch commissioner in New Sweden, wrote that a Swedish lieutenant and twenty-four soldiers had come to his house one day and cut down all his trees, even the fruit trees.

Stuyvesant stamped about louder than ever when he heard this. The insult to the Dutch commissioner seemed the worst thing that had yet happened; and he made up his mind to sail down to New Sweden and remonstrate with the Swedish Governor Printz himself.

Governor Printz lived in a very handsome house called Printz Hall, on Tinnicum Island. All about it were fine gardens and an orchard. There was also a pleasure house, and indeed everything that could help to make it comfortable and convenient. Governor Printz received Governor Stuyvesant very politely in the great hall of the house, and presently the two governors sat down and began to talk. Stuyvesant complained bitterly of the treatment the Dutch had received in Delaware. He repeated that by[37] rights the Dutch really owned the land; they had bought it years before from the Indians, and their right to it had been sealed by the blood they had shed upon its soil.

Printz himself was a very violent man, and often gross and abusive; but this time he kept his temper and answered the Dutch Governor civilly. Stuyvesant, though, gained nothing by his visit, and all his talk and reasoning. Printz was determined to keep all the land along the Delaware, and to govern it as he pleased. As to cutting down Hudde’s trees, he said he had had nothing to do with that matter, and was sorry it had happened.

So Stuyvesant went back to his own fine house at New Amsterdam, and the Dutch in New Sweden were no better off.

However, he was not one to let the matter rest at that. He kept it in his mind, and at last, as the result of his thinking, he sent messengers to all the Indian sachems along the Delaware, inviting them to come to a great meeting at the governor’s house in New Amsterdam.

The meeting was set for early in July; and, on the day appointed, the Indians came. They were grave and fierce looking, in spite of their gay paint and feathers. Stuyvesant received them in the hall of his house; and after they had all arrived, they sat down there in council.

The first thing Stuyvesant wished to learn from them was exactly how much land they had sold to the Swedes.

The Indians told him they had not sold any land to the Swedes, except that upon which[38] Fort Christina stood, and ground enough around it for a garden to plant tobacco in.

“Then will you sell the land to us?” asked Stuyvesant.

The Indians were quite willing to do this. They were always willing to sell anything, even if they had already sold it; but what they wished to know was what the Dutch would give. The price finally agreed upon was, if they had only known it, an absurd price indeed; but the Indians were quite content with it. It was;—12 coats of duffels (a kind of cloth), 12 kettles, 12 axes, 12 adzes, 24 knives, 12 bars of lead and 4 guns with some powder; besides this, the Dutch to repair the gun of the Chief Penomennetta when it was out of order, and to give the Indians a few handfuls of maize when they needed it. This was the price for which the Indians sold to the Dutch all the land along the Delaware River, from Fort Christiana to Bombay Hook.

The Indians then went away, very much pleased. Governor Stuyvesant, too, was in high good humor. Now he would show Printz who was the real owner of the land.

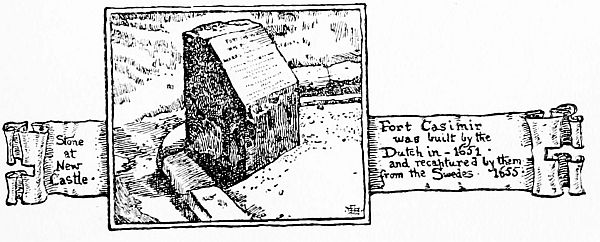

In the year 1651, Stuyvesant set about having a fort built at New Amstel, (now New Castle) about five miles south of Fort Christina. The name of it was to be Fort Casimir.[1] This fort was of great value to the Dutch, and Stuyvesant felt that he had taken the first step toward recovering Dutch possession of the Delaware.

Printz, as soon as he knew what Stuyvesant was about, protested against the building of the[39] fort; but he was not strong enough to prevent it. He had grown very unpopular, because of his violent and coarse temper. He was hated not only by the Dutch and the English, but by his own people as well. Things began to grow more and more unpleasant for him, so that at last he begged to be allowed to go back to Sweden; and in 1653 he left the shores of New Sweden and his house on Tinnicum Island, and sailed away not to return.

But Stuyvesant was well pleased. He felt that it was he, with his building of Fort Casimir, who had driven the Swede away. He smiled comfortably to himself as he sat smoking his pipe, and made fresh plans.

But in June, 1654, news came to Governor Stuyvesant that made him leap from his chair and clench his hands and stamp up and down as though he would break his wooden-silver leg to pieces. The Swedes had taken Fort Casimir! And they had taken it without a single blow having been struck by the Dutch. The taking of the fort was in this way:—

Rysing, the new Swedish governor, had arrived at Godwin Bay early in May. He came sailing up the South River in the good ship Aren, and with him came a number of new settlers, bold and resolute men, about two or three hundred in all.

As they came near Fort Casimir they fired a royal salute, dropped their sails, and anchored. This was May 31, 1654. Gerritt Bikker, the commander of the fort, immediately sent to ask[40] their business in these waters. Bikker was a very weak and timid man.

The messengers soon returned, bringing word that it was a Swedish ship with the new Governor, and that he demanded to have Fort Casimir handed over to him, as it was on Swedish land.

Bikker was amazed at this message, and was about to write out an answer when he was told that a boat from the Swedish vessel was coming toward the Fort, with about twenty men.

Bikker thought that they were bringing some further message, and politely went down to the beach to meet them. The gate of the fort was left open.

The Swedes landed; but, instead of stopping on the beach, they marched straight to the open gate and into the fort. Then, drawing their swords, they demanded the surrender of the fort. At the same time two shots were fired from the Swedish vessel, and the Swedes in the fort wrenched the muskets from the hands of the Dutch soldiers. The whole thing was so sudden that the Dutch were unable to make any resistance, and in a moment they had been chased from the fort, and the Swedes had taken possession of everything.

All this happened on Trinity Sunday, so the Swedes now changed the name of the fort from Fort Casimir, to Fort Trinity.

The Dutch living near the fort, took the oath of allegiance to the Swedish crown, and it seemed that Stuyvesant was to lose everything he had just gained in Delaware.

It was felt to be very important at this time to gain the friendship of the Indians, so, very soon after the capture of Fort Casimir, Governor Rysing asked the Delaware sachems to come to a meeting at Printz Hall.

The Indians came to Tinnicum Island in answer to his message as, a short time before, they had gone to New Amsterdam when Stuyvesant sent for them. They were seated in the great hall of the house and waited gravely to hear “a talk made to them.”

Rysing began by telling the Indians how much the Swedes respected them. He reminded them of the gifts they had received from the Swedes—many more than the Dutch had ever given them.

The Indians replied that the Swedes had brought much evil upon them; that many of them had died since the Swedes had come into the country.

Rysing then gave them some presents, and after that the Indians arose and went out.

Presently they returned; and the principal sachem, a chief called Naaman, “made a talk.” He began by saying that the Indians had done wrong in speaking evil of the Swedes; “for the Swedes,” said he, “are a good people; see the presents they have brought us; for these they ask our friendship.” He then stroked his arm three times from the shoulder down, which among the Indians, is a sign of friendship. He promised that the friendship between the Indians and the Swedes should be as close as it had been in Governor Printz’s time.

“The Swedes and the Indians then,” he said, “were as one body and one heart” (and he stroked his breast as he spoke), “and now they shall be as one head,” and he seized his head with both hands and then made a motion as though he were tying a strong knot.

Rysing answered that this should indeed be a strong and lasting friendship, and then the great guns of the fort were fired.

The Indians were delighted at the noise and cried, “Hoo, hoo, hoo; mockirick pickon!” which means, “Hear and believe! The great guns have spoken.”

After more talk great kettles were brought into the hall filled with sappawn, a kind of hasty pudding made of Indian corn, and all sat down and fed heartily, and then the Indians departed to their villages.

Rysing had thought that as soon as Stuyvesant heard that the Swedes had taken Fort Casimir, he would try to recapture it; but day after day and week after week passed peacefully by. Rysing began to believe that Stuyvesant meant to let the matter rest.

But the hot-tempered Dutchman had far other ideas than that. He still remembered that he had been told to keep peace with his neighbors, but he wrote an account of the whole matter to the West India Company at home. Then he had to gather together all his patience and wait, for an answer from across the ocean. What he most feared was that he would be told still to keep the peace.

But when Stuyvesant’s letter telling how the Swedes had taken Fort Casimir reached Holland, the people were aroused at last. The roll of drums sounded in the streets of old Amsterdam. Volunteers were called for. A ship, The Balance, was fitted out with men, arms, ammunition and provisions, and set sail as quickly as possible for New Netherlands.

Great was the joy of Stuyvesant to receive such an answer as this. He too had called for volunteers, and he had gathered together all the vessels he could; he had even hired a French frigate, L’Esperance, which happened to be lying in the harbor of New Amsterdam at that time.

About the middle of August, 1655, the little Dutch fleet sailed out from the harbor of New Amsterdam-seven vessels in all and carrying almost seven hundred men. Stuyvesant himself was in command.

They sailed down to the Delaware Bay, in between the capes, and up the river to a short distance above the fort. Quietly as Styuvesant had moved, the Indians had learned his plans some time before, and had carried the news of them to Rysing.

Rysing had immediately sent what men and ammunition he could spare to Fort Trinity, and had told Captain Sven Schute, its commander, to fire on the Dutch if they attempted to sail past the fort. This, Sven Schute did not do. He allowed the Dutch to pass by without firing a single shot, and so all communication with Fort Christina was cut off.

Stuyvesant landed the Dutch soldiers on Sunday, September 5, 1655, and sent Captain Smith with a drummer to the fort to demand that Captain Schute should surrender it, as it was Dutch property.

Schute, however, asked time to consider, and also to be allowed to write to Rysing.

This was refused; and Schute was again called upon to surrender, and so spare the shedding of innocent blood.

A second time he refused, and a third time he was asked to surrender; and the third time he agreed and opened his gates to the Dutch. So it was that within a short time after leaving New Amsterdam, the Dutch marched to the fort with music playing and banners flying; and so, a second time, Fort Casimir (then Fort Trinity) was captured without a blow having been struck or a drop of blood shed.

After capturing Fort Casimir, Stuyvesant sailed up the river to Fort Christina and surrounded it. Rysing had only thirty men, and around him camped almost seven hundred Dutchmen.

Stuyvesant sent him a message by an Indian, bidding him surrender the fort.

Rysing, by the same Indian, returned a letter begging Stuyvesant to meet him and talk the matter over.

This Stuyvesant agreed to; but he treated Rysing in such an insolent way that it made matters harder than ever for the Swedish governor to bear. Rysing laid before him all the Swedish claims to the river, and begged him to[45] withdraw his soldiers. This, Stuyvesant refused to do, and again demanded the surrender of the fort.

Rysing would not agree to this and so returned.

On the twenty-fourth of September all the Dutch guns were turned upon Fort Christina, and Rysing was again called upon to surrender.

This time, seeing how useless it was to try to defend the fort with his small force, he agreed. Such terms as he could, he made with the Dutch.

He and his troops were allowed to march out with drums beating, fifes playing, and colors flying, and they were also allowed to keep their guns and ammunition and all effects belonging to the Swedish Crown. It was agreed that no Swedes were to be kept there against their will; but any were to be allowed to stay one year if they wished, in order to arrange their affairs. Rysing and his Swedes were also to have a ship to take them back to Gottenburg in Sweden.

Thus, on September 25, 1655, our state became the property of the Dutch, and Swedish power ended forever on the banks of the Delaware.

[1] The spot where Fort Casimir (or Trinity) once stood, is now covered with water, the Delaware flowing over it. It was a little north of where the town of New Castle now stands. A boulder with an inscription has been placed near the shore, on the road, by the Colonial Dames, to mark the vicinity of the old fort.

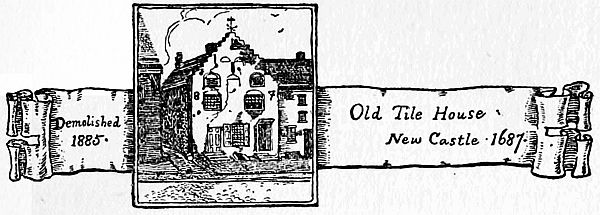

IT WAS in the year 1682, and Delaware had seen many changes since Peter Minuit and his little band of Swedes had landed on her wild shores. During those years the Swedes had been driven out by the Dutch, and the Dutch had afterward surrendered to the English; then the Dutch, growing stronger, had driven out the English; but again the English had taken possession and now owned all of what had once been New Netherlands and New Sweden. New Netherlands was now called New York, and it was the English Directors, (living in the town of New York, formerly New Amsterdam), who made the laws for Delaware.

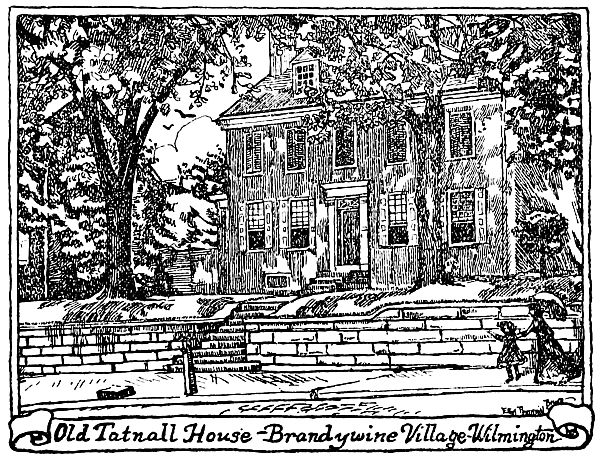

Only a few English, however, had come to Delaware to live. The people of Wilmington (once Christinaham, or Christina Harbor) and of New Castle, were principally Dutch and Swedes. They were simple farmer people, raising crops and cattle and chickens, and they were very willing to keep the laws that the English at New York made for them. The Indians were still[52] troublesome at times, but the settlers had their block-houses or forts to retreat to and were generally able to protect themselves.

But now it had come to their ears that a new governor was coming out from England to rule over them, and they wondered anxiously what sort of man he would prove to be. Governor Printz had been coarse and violent; Governor Stuyvesant, hot-tempered, ambitious, and overbearing; and terrible tales had been told of the cruelty of Governor Kieft. There had been a long line of governors since Minuit’s time, both in Delaware and in New York; and few of them had seemed to care for the good of the poorer people. And now this new man was coming and, for all they knew, might be the worst of all.

The name of the new Governor was William Penn. The Duke of York had given Delaware to him, and King Charles the Second, had given him a great tract of land farther to the North, which he called Pennsylvania. More than this, the people did not know; but they often talked about the new governor and wondered what he would be like, and when he would come, as they sat around their fires in the early fall evenings.

Then they began to learn more about him; for his cousin, Captain William Markham, came out to America to act as Governor till Penn could come himself. They learned that Penn belonged to the Quakers—a strange, new religious sect; and that it was the rule that Quakers must dress very plainly and say “thee” and “thou” to people instead of “you” and take off their hats to nobody, not even the King himself. That[53] seemed a strange thing indeed to the settlers, and they wondered how the King liked it.

Penn had bought the land from King Charles, and his brother the Duke for an absurd price—a price so small that the poorest farmer among them all might have bought it if he had had the chance.

For all of Pennsylvania, with its wooded hills and fertile valleys and well-stocked streams, he had paid only twelve shillings[1] and, at Michaelmas, was to pay the King five shillings more.

For Delaware, he had paid ten shillings to the Duke of York; and every Michaelmas he was to pay to the Duke, a rose. He was also to pay over one half of the profits he drew from the southern part of Delaware. Yes, any of the honest farmers might have bought the land at that price, but then, the great people most probably would not have sold it at all to anyone but their friend, William Penn.

Captain Markham was buying for Penn, from the Indians such rights as they had in the land, and was paying them well—better than they had ever been paid before—so perhaps the new governor was a generous, fair minded man after all.

So, in talk and wonderings, the days slipped by. September had passed, and October was almost gone, before the governor’s English ship, the Welcome, was sighted coming up the river from the bay. The news of its coming spread from house to house, and from farm to farm, and even back into the country to the villages of the Indians.

All work was laid aside, and the people of New Castle and the country round about gathered down at the shore to watch the approach of the vessel. Captain Markham himself was there, gorgeous in his English uniform, having come down to New Castle to meet his cousin.

Nearer and nearer came the ship, looming up bigger and bigger, stately and slow, its sails spread wide, and the English colors fluttering at its masthead. Then it came about, and the great anchor dropped into the water with a splash. Boats were lowered, and the people of the vessel clambered down into them and were rowed toward the shore. In the very first boat came William Penn himself.

He was a tall, noble looking man, with large, dark, kindly eyes, and hair that fell in loose locks to his shoulders. He was very simply dressed, as were all the men with him. The only way in which his dress differed from theirs was that he wore a light blue silken sash around his waist. He was worn and thin, and some of his companions looked even ill.

This was not to be wondered at, for he told his cousin that soon after they had set sail from England, smallpox had broken out on board the Welcome. Of the one hundred men who had started with him, almost one-third had died on the voyage. The colonists heard afterward of the goodness of William Penn to the sick. He himself had never had smallpox, but everyday during the voyage he went down to the bedsides of the sufferers. He gave them medicines,[55] talked with them and cheered them, and ministered to the dying.

It had indeed been a terrible voyage. Fortunately, the ship had been well stocked with provisions of every kind, and many luxuries.[2] Still, these could ease but little the sufferings of the sick, shut up for two months in that rolling, tossing vessel. A blessed sight the shores and wooded hills of Delaware must have been to those sick and weary voyagers.

As Penn landed, Captain Markham came forward eagerly to greet him. It was a strange and varied crowd that had gathered there to meet their governor—Swedes, Dutch, Germans and Welsh, many of them dressed in their national costumes, and back of them the tall, red skinned Indian, Sachem Taminent, with his party of Leni Lenapes in their paint and feathers.

Penn was escorted by his cousin and the principal men of the village, to the house that had been made ready for him, there to eat and rest after his long journey.

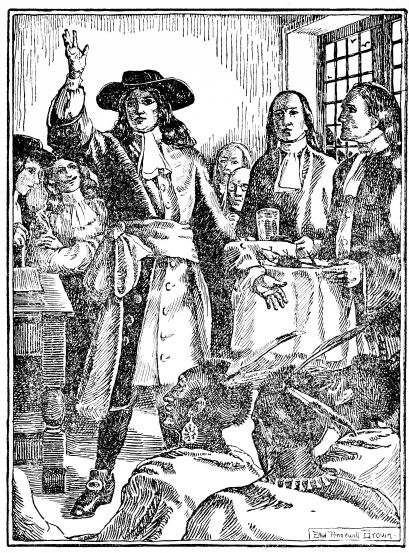

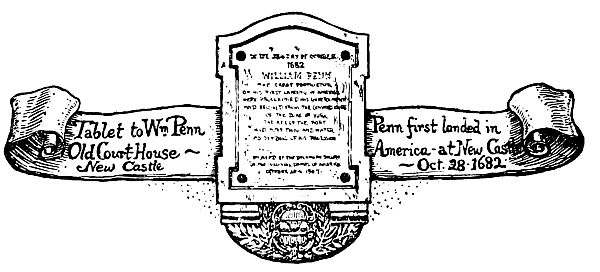

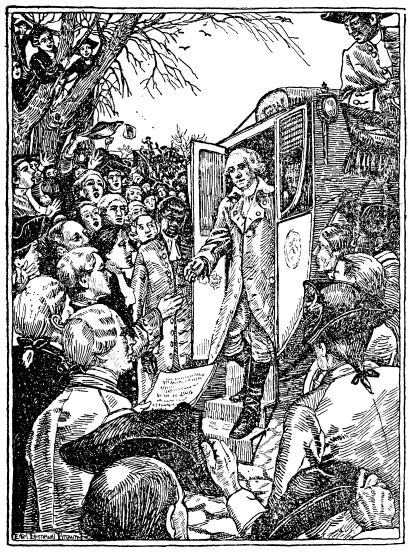

The next day, October 28, 1682, the new governor went to the Courthouse to speak to the people. The room was thronged with those who crowded in to hear him. Before he began, however, two gentlemen, John Moll and Ephraim Herman, performed what is called “livery of seisin;” that is, they gave to Penn earth, water, a piece of turf, and a twig, in token that he was ruler there of land and water and of the fruits of tree and field.

After that, Penn spoke to the people with such kindness, that their simple hearts were[56] filled with joy. He bade them remember that they were “but as little children in the wilderness,” and under the care of one Father. He told them that he wished to found a free and virtuous state in which the people should learn to rule themselves. He promised that every man in his provinces should “enjoy liberty of conscience,” and have a voice in the ruling of the colony.

The people listened to him in deep silence; and when he ended his speech, they had but one thing to beg of him, and that was that he would stay among them at New Castle and rule over them. This he told them he could not do; and then they begged him to join their territory to Pennsylvania, that the white settlers might have one country and one ruler. He promised to consider this, and then he bade them good-bye and returned to the ship.

The sails of the vessel were spread wide like great wings of peace, the wind filled them, and slowly the ship began to move. The colonists upon the shore still lingered there, gazing after her, and straining their eyes to see, as long as they could, the tall man that stood there in the stem with a light blue sash around his waist At last they could see him no longer, and then they turned and went back to their daily toil.

Penn did not forget them or his promise to them. At the first General Assembly held at Chester, it was declared that the two provinces were united, and that the laws that governed one should be for the other too.

In 1701, Penn visited New Castle again and was received with joy by its people.

A few years later he made the town a gift of one thousand acres of land lying to the north of it, to be used as a public commons by its people and to belong to them.

This tract of land still belongs to the town of New Castle, but since 1792 it has been rented out in farms, and is no longer a public commons.

William Penn did much to bring the Indians into truer friendship with the settlers. He treated them justly. He trusted them and went among them unarmed and unprotected. He walked with them, attended their meetings and ate of their hominy and roasted acorns. One time it happened the Indians were showing him how they could hop and jump, and after sitting watching them for a time, the Governor rose up and out-jumped them all.

Penn’s word was trusted by Indians and settlers alike, and they knew their interests were as safe in his hands as in their own.[3]

New Castle has just cause for pride in the fact that William Penn’s first landing in America was made upon her shore.

[1] About two dollars and a half.

[2] In a list of creature comforts put on board a vessel leaving the Delaware, on behalf of a Quaker preacher, are enumerated:—32 fowls, 7 turkeys and 11 ducks, 2 hams, a barrel of China, oranges, a large keg of sweetmeats, ditto of rum, a pot of Tamarinds, a box of spices, ditto of dried herbs, 18 cocoanuts, a box of eggs, 6 balls of chocolate, 6 dried codfish, 5 shaddock, 6 bottles citron water, 4 bottles of Madeira, 5 dozen of good ale, 1 large keg of wine and 9 pints of brandy, as well as flour, sheep, and hogs.—Dixon’s “William Penn.”

[3] Among the articles used in trading with the natives was rum. The colonists at that time did not seem to see how dangerous it was to let them have it. Several years later, however, the Friends (Quakers) had a meeting with the natives, in order to put a stop to the sale of rum, brandy, and other liquors. There were eight Sachems present, and one of them made this speech.

“The strong liquor was first sold us by the Dutch, and they are blind, they had no eyes, they did not see it was for our hurt. The next people that came among us were the Swedes, and they too sold strong liquors to us; they were also blind, they had no eyes, they did not see it was hurtful to us to drink it, although we knew it was hurtful to us; but if people will sell it to us we are so in love with it that we cannot forbear. When we drink it, it makes us mad; we do not know what we do; we then abuse one another, we throw each other into the fire; seven score of our people have been killed by reason of drinking it. But now there is a people come to live among us that have eyes, they see it be for our hurt, and are willing to deny themselves the profit of it for our good. Now the cask must be sealed up, it must not leak by day or night, in light or in the dark, and we give you these four belts of wampum to be witnesses of this agreement.” One bargain made with the Indians, included the gift of one hundred jew’s-harps.

YEARS passed, and the Counties on the Delaware,[1] under the wise laws of William Penn,[2] grew and prospered. Dover was laid out and settled; New Castle flourished; Lewes became a town. Instead of the rough buildings of the early settlers, handsome country houses and comfortable farms were to be seen.

The manners and customs of the people were still very plain and simple. Very few foreign articles were used in this part of the country. Clothes were woven, cut and sewed at home. Beef, pork, poultry, milk, butter, cheese, wheat and Indian corn were raised on the farms; the fruit trees yielded freely, and there was a great[64] deal of wild game; the people lived not only comfortably but luxuriously.[3]

The Counties on the Delaware were very fertile, and very little labor was needed to make the land yield all that was required. The people had a great deal of leisure time for visiting and pleasure. They were always gathering together at one house or another, the younger people to dance or frolic, and the older men to amuse themselves with wrestling, running races, jumping, throwing the disc and other rustic and manly exercises.

On Christmas Eve there was a universal firing of guns, and all through the holidays the people traveled from house to house, feasting and eating Twelfth cake, and playing games.[4]

So for years, life slipped pleasantly by in these southern Counties, and then suddenly there came a change. There began to be talk of war with England. News was eagerly watched for. There was no mail at that time. Letters were carried by stage-coach, or by messengers riding on horseback from town to town. In the old days, the people had been content to send their servants for letters. Now, when a messenger, hot and dusty, came galloping into the town, a crowd would be waiting, and would gather round him.

And it was thrilling news that the dusty messengers carried in those days, the days of 1775. England was determined to tax her colonies, and the colonies were rising in rebellion. Boston had thrown whole cargoes of tea into her harbor rather than pay the tax on it.

Then the first shots of the Revolution were fired at Concord and Lexington. At the sound of those shots the Counties on Delaware awoke. Drums were beat, muskets were cleaned, ladies sewed flags for the troops to carry; men enlisted, and the militia drilled. But still it was hoped by many that things would settle back peaceably.

But worse and worse news came from the north. Boston harbor had been shut up by the English. The people were starving. War ships from England had brought over more troops (many of them hired Germans), and had quartered them on the town. All the country was hot with anger over these things. Food and clothing were sent to Boston. General Washington raised troops of a thousand men, at his own expense, and marched north to her relief.

General Caesar Rodney was one of the important men of Dover at that time. He was a tall, pale, strange looking man, with flashing eyes, and a face, as we are told, “no larger than a good sized apple.” He was a general in the militia, and was heart and soul for independence. He rode about the country, calling meetings, speaking to the people, and urging them to enlist, and urging them, too, to raise money to give to the government. He was at this time suffering from a painful disease, but he spared neither strength nor comfort in the cause of freedom.

Mr. George Read of New Castle, was a very important man in the colonies, too. He was a patriot, and belonged to the militia, but he was very anxious not to begin a war. He argued that England had spent a great deal of money on[66] her American colonies, and that she had a right to try to get some of it back by taxing them. He agreed that the time might come when the colonies would have to be free, but he thought that time had not yet come. He hoped that when it did, the colonies might win their freedom peaceably, and not by battle and bloodshed. He was a calm, quiet, learned man, rather slow of speech, and different in many ways from his quick and fiery friend, Rodney.

A third man who was important in Colonial times was Mr. Thomas McKean. He was a lawyer in New Castle, and was a friend of both these men. Like Rodney, he was for freedom at any cost.

In 1776, when the Colonial Congress was called to meet in Philadelphia, these three men, Rodney, Read and McKean, were sent to it as delegates by the Counties on the Delaware.[5]

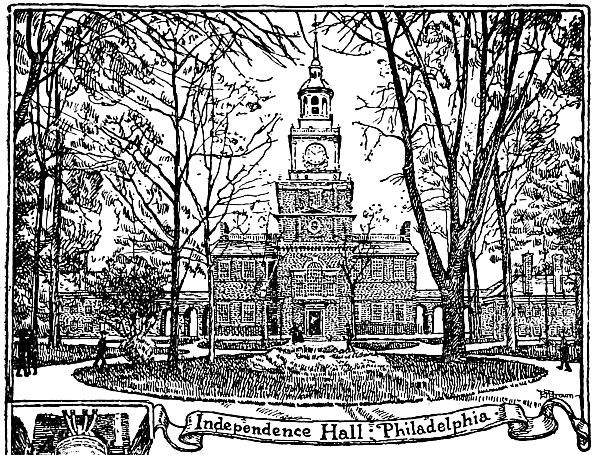

This meeting of Congress in the summer of 1776 was the most important meeting that had ever been held. From north and south the delegates came riding to it, from all the thirteen colonies; and they met in the Committee Room of the State House in Philadelphia.

Many serious questions were to be decided by these delegates this year. But the most serious of all the questions was whether the Colonies should declare themselves free and independent states. If they did this, it would mean war with England.

While the question was still being argued about in the committee room, Caesar Rodney was sent for to come back to the Counties on the[67] Delaware. Riots and quarrels and disturbances had broken out there, and no one could quiet them as well as Caesar Rodney. He was very glad to go, for it seemed as though it might be a long time before the delegates would decide on anything, and he hoped to be able to raise some money for the government.

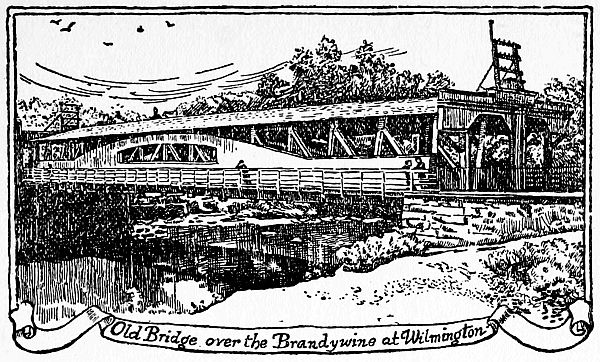

He started out early one morning on horseback, cantering easily along through the cool of the day. It was eighty miles from Philadelphia to Dover, and he broke it by stopping over night at New Castle, which was rather more than half way home. The road he took was the old King’s Highroad, which ran on down through the Counties on Delaware, through Wilmington and New Castle and Dover, as far as Lewes.

General Rodney found a great deal to do down in the Counties. The Whigs and Tories had come to blows. One Tory gentleman only just escaped being tarred and feathered, and carried on a rail. Caesar Rodney was the one who had to quiet all the troubles. Beside this he made speeches, raised moneys and helped get together fresh troops of militia.

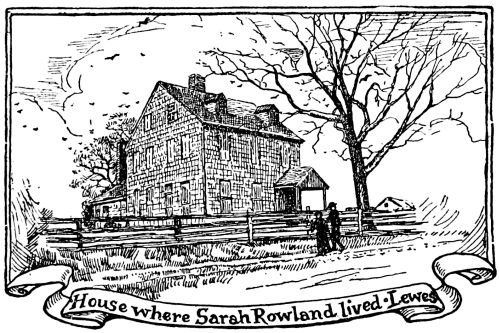

But busy though he was, he managed to find some time for visiting about among his friends. Especially he found time to visit at the house of a young Quaker widow named Sarah Rowland. Mistress Rowland lived in Lewes. She was a Tory, but she was very beautiful and witty, and Caesar Rodney was said to be in love with her. He might often have been seen, between his busy times, cantering along the road that led to Lewes and to her house. Mistress Rowland, as a[68] Quaker, believed all fighting to be wrong, but she was always friendly with the General. Perhaps she hoped in some way to be able to help the Tories by things the General told her, or by having him at her house. At any rate she always made him welcome.

Now, while General Rodney was still busy down in the Counties on the Delaware, with his work and pleasure, great things were happening in Philadelphia. The Declaration of Independence was finally drawn up and written out.

It was laid on the table before the Colonial Congress, and the delegates were given five days to make up their minds to agree, whether they would sign it or not. They considered and discussed it in secret behind closed doors.

One after another, the delegates from various colonies agreed to sign. At last, only the Counties on the Delaware were needed to carry the agreement. They could not sign the Declaration, for they had now only two delegates present at Congress. Of these, one (McKean) was for it, and one (Mr. Read) was against it, so it was a tie between them, and Rodney, whose vote could have decided the matter, was down in the Counties on Delaware, eighty miles away.

McKean was in despair. He sent message after message, down to Delaware, begging the General to return to Philadelphia and give his deciding vote, but no answer came. The fact was that General Rodney did not receive any of these messages McKean sent. He was visiting Mistress Rowland in Lewes at the time, and she managed to keep the letters back from him.[69] She hoped that he might know nothing about the Declaration until it had been voted on and the whole matter decided. Even if all the other Colonies decided to sign, it would weaken the union very much if the Colonies on the Delaware did not sign.

On the third of July, McKean sent a last message down to Rodney, passionately begging him to come to Philadelphia. The vote of the delegates was to be taken July the fourth, and if the General was not there the vote of the Counties on Delaware could not be cast for the Declaration of Independence, and it might be lost.

On this same day, July the third, 1776, Caesar Rodney was chatting with Mistress Rowland in the parlor of her house at Lewes. It had seemed strange to him that he had not heard from McKean lately, but he felt sure that if anything important was happening at Philadelphia he would receive word at once. So he put his anxieties aside and laughed and talked with the widow.

Suddenly, the parlor door was thrown open and a maid-servant came into the room. She crossed over to where General Rodney was sitting. “There!” she cried. “I’m an honest girl and I won’t keep those back any longer!” and she threw a packet of letters into the General’s lap.

Rodney picked them up and looked at them. They were in Mr. McKean’s hand-writing. Hastily he ran through them. They were the letters Sarah Rowland had been keeping back,—the[70] letters begging and imploring him to hasten north to Philadelphia.

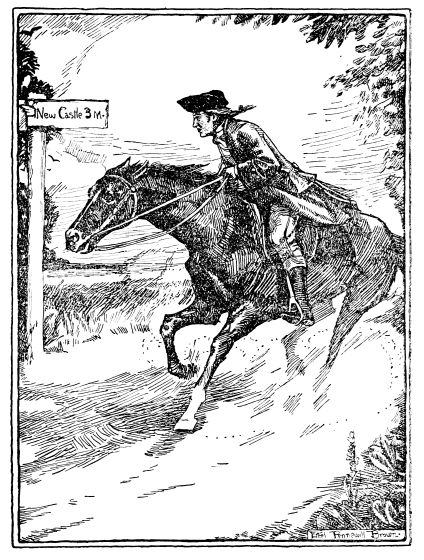

Without a word, General Rodney started to his feet, and ran out to where his horse was standing before the house.[6] Sarah Rowland called to him, but he did not heed her. He sprang to the saddle and gathered up the reins, and a moment later he was galloping madly north toward Dover. It was a long ride, but a longer still was before him. The heat was stifling, and the dust rose in clouds as he thundered along the King’s Highroad.

At Dover, he stopped to change his horse, and here he was met by McKean’s last messenger, with a letter, urging him to haste, haste. Indeed, there was not an hour to waste. Philadelphia was eighty miles away, and the vote was to be taken the next morning.

On went Rodney on his fresh horse. Daylight was gone. The moon sailed slowly up the sky, and the trees were clumps of blackness on either hand as he rode.

At Chester, he again changed horses, but he did not stop for either rest or food. Soon, he was riding on again.

It was in the morning of July fourth, that the rider, exhausted and white with dust, drew rein before the State House door in Philadelphia. McKean was there watching for him.

“Am I in time?” called Rodney as he swung himself from his horse.

“In time, but no more,” answered McKean.

Side by side he and Rodney entered Independence Hall. There sat the delegates in a semi-circle.[71] Rodney and McKean took their places. The Declaration of Independence lay on the table before them. It was being voted on. One after the other the colonies were called on and one after another they gave their votes for it. The Counties on Delaware were called on. Mr. McKean rose and voted for it. Mr. Read was, as usual against it.

Then Caesar Rodney rose in his place. His face looked white and worn under its dust, but he spoke in a clear, firm voice. “I vote for Independence.”

And so the day was won. From the belfry of Independence Hall, the bells pealed out over the Quaker City. Bonfires blazed out, people shouted for joy, and the thirteen American Colonies, strong in union, stood pledged together for liberty.

[1] It was not until after the Declaration of Independence that these “Counties upon the Delaware” received the name of Delaware State, and not until 1792 that it was called the “State of Delaware.”

[2] Edmund Burke spoke of Penn’s Charter to his colonies of Pennsylvania and Delaware as “a noble charter of privileges, by which he made the people more free than any people on earth, and which by securing both civil and religious liberty caused the eyes of the oppressed from all parts of the world to look to his counties for relief.”

[3] This account of the life in Delaware before the Revolutionary War is taken from a letter from Thomas Rodney, a younger brother of Caesar Rodney.

[4] The land upon which Dover stands was bought from the Indians in 1697, for two match coats, twelve bottles of drink and four handfuls of powder.

[5] Rodney, Read and McKean were appointed Delegates in March, 1775.

[6] While Caesar Rodney’s famous ride is a story of which Delaware is proud, the exact time when he started, and the place he started from have been much disputed. One tradition says that he left Sarah Rowland’s house at Lewes, and another tradition insists that he started from his own house near Dover. As for the hours of starting and arrival, the archives show how different the versions are. After much thought and trouble, the Colonial Dames have decided to choose the most detailed tradition as being possibly also the most accurate. They do not claim to decide the matter, which will always, probably, remain unsolved.

The following was the Congress express rider’s time from Lewes to Philadelphia: Leave Lewes at noon, reach Wilmington next day at 4 o’clock, A. M. Or leave Lewes at 7 o’clock, P. M., Cedar Creek, 10:30; Dover, 4:15; Cantwell’s Bridge, 9:05; Wilmington, 12:55; Chester, 2:37; arrive Philadelphia 4 o’clock P. M., or 21 hours. (See American Archives.)

THE little town of Lewes is on Delaware Bay, with rolling dunes of sand between it and the ocean. The winds that blow over it have the smell and taste of salt in them, and in the sky overhead, the grey seagulls soar and hover.

There was a time, long ago, when pirates sailed the Delaware waters. Sometimes they landed there, and drank and plundered and put the people in fear of their lives. There is a story that Captain Kidd buried much treasure somewhere among these dunes.

But that was long before the American colonies went to war with England, and in Revolutionary times it was not pirates that Lewes was afraid of, but English warships.

From Delaware Bay the Delaware River lies, wide and open, all the way to Philadelphia. An enemy’s ship that entered the bay could easily sail on up the bay and river, past New Castle, Wilmington and Chester,—and might bombard Philadelphia from the water-front. This was[78] what the Committee of Safety feared the British would do when the Revolutionary War began, so a guard was set at Henlopen light house.

It was in the last week of March of the year 1776, that the first British war vessel entered Delaware Bay. This vessel was a frigate called “Roebuck.” She came sailing slowly in, the black mouths of her guns threatening the town, and anchored in the bay. Her tender followed her, and she too was armed with guns.

Then all Lewes was in a stir. Messengers were sent riding in hot haste to Philadelphia, and all along the way they spread the news that the British ships had arrived. Colonel John Haslet came marching down to Lewes at the head of the Delaware militia, so as to be ready to protect the town against the English, in case they tried to land.

This, however, the British did not try to do. They cruised up and down in the “Roebuck,” or lay at anchor in the bay.

They managed to capture a pilot boat named the “Alarm,” near Lewes, and they fitted her out as a second tender. A little later they made a prize of an American sloop called the “Plymouth.” All the men from the tender were put on board this new prize except a lieutenant and three soldiers who were still left on the “Alarm,” to take care of her. But that night the helmsman on the “Alarm” fell asleep; the boat drifted on shore, and the lieutenant and his men were taken prisoner by the Americans.

There had as yet been no shots exchanged between the Americans and the English. But one bright, clear Sunday morning in April, word was brought to Colonel Haslet that an American[79] schooner had anchored just off the shore below Cape Henlopen. The captain wished him to send men to help unload her. She carried supplies for the Americans.

Unluckily, news of the schooner reached the British, too, and at the same time that Haslet’s men started by land to help the captain unload, the British tender started by sea.

The Americans made all the haste they could, but they were obliged to cross a creek before they could reach the place where the schooner lay. The country people brought boats and ferried them over, but the soldiers soon saw that the tender was out-racing them.

The captain of the schooner saw this, too, and rather than have his cargo fall into the hands of the British, he set his sails, and ran ashore.

As soon as the American soldiers arrived they began to fire at the tender, but she kept too far away for their bullets to reach her. Seeing this, they laid aside their muskets and set to work to help the sailors unload the schooner.

The tender kept firing at them all the while they were unloading, but her shots fell harmlessly in the sand. Several of the soldiers picked up the balls as they fell, and carried them home to show to their families.

The tender now sent a barge back to summon the “Roebuck,” and presently, the frigate came sailing around the Cape at full speed to help the tender. She swept down toward the schooner like a great bird, but presently she found she was running into shoal water. She was obliged to come to anchor just off the Hen-and-Chicken shoals, but from there she began to fire at the soldiers and the schooner.

The Americans now turned the schooner’s guns on the frigate and tender. They saw a gunner on the frigate throw up his arms and fall. A number of the English were wounded, but not a single American was hurt. Presently, the frigate, finding it a losing game, sailed back around the Cape and out of reach.

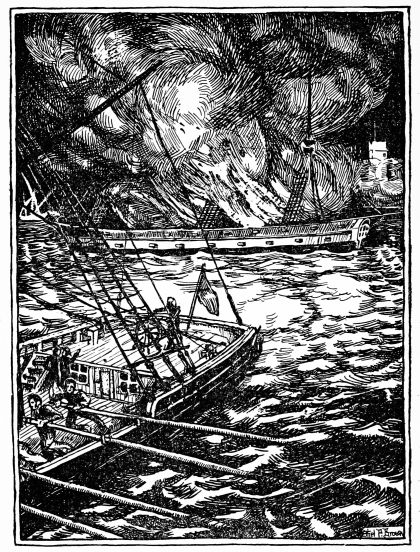

No more shots were exchanged between the English and American vessels until May. Early in that month the “Roebuck” was joined by the sloop “Liverpool,” and the two with their tenders sailed straight up the bay and river toward Wilmington. Then they moved to and fro, between Chester and New Castle.

News of their coming went before them. At New Castle, houses were closed, and the people loaded their goods in wagons and carriages and fled back into the country.

At Wilmington, a number of row-galleys (some thirteen in number) were gathered and furnished with guns and ammunition, and were made ready in every way to give battle to the enemy. The galleys were under the command of Captain Houston, of Philadelphia.

It was on the morning of the eighth of May, that the British sails were seen coming up the river. Great crowds of people had gathered on the banks to watch the battle.

It was not until the British vessels were almost opposite Christiana creek that the firing began. The dull boom of the guns echoed and re-echoed from the wooded hills of the Brandywine. Great puffs of grey smoke drifted across the water. Sometimes the vessels were almost hidden.

In the midst of the battle, four Wilmington boys started out from the shore, armed with[81] some old muskets that they had somehow got hold of. They boldly rowed out through the smoke until they were directly under the stern of the “Liverpool,” and then they began to fire at her. Presently, an officer on the sloop saw them.

“Captain,” he called to his commanding officer, “do you see those young rebels? Shall I fire on them?”

The brave old Captain Bellew shook his head. “No, no,” he cried; “don’t hurt the boys. Let them break the cabin windows if they want to.”

That indeed, was about all the damage the young patriots were able to do. When they had used up their ammunition, they rowed back to the shore again unhurt.

While the firing was still at the hottest, a major of artillery came riding at full speed. He threw himself from his horse, and begged a couple of boatmen who were standing with the crowd, to row him out to the galleys; he wished to have a chance to fire a shot at the enemy.