The Project Gutenberg EBook of Touring in 1600, by Ernest Stuart Bates

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Touring in 1600

A Study in the Development of Travel as a Means of Education

Author: Ernest Stuart Bates

Release Date: March 27, 2015 [EBook #48594]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TOURING IN 1600 ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, MWS and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

TOURING

IN 1600

A Study in the Development of Travel as a Means of Education

By E. S. Bates

With Illustrations from Contemporary Sources

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

1911

COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY E. S. BATES

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published September 1911

TO

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Some of the Tourists | 3 |

| II. | Guide-Books and Guides | 35 |

| III. | On the Water | 60 |

| IV. | Christian Europe | |

| PART I. EUROPEAN EUROPE | 95 | |

| PART II. THE UNVISITED NORTH | 154 | |

| PART III. THE MISUNDERSTOOD WEST | 162 | |

| V. | Mohammedan Europe | |

| PART I. THE GRAND SIGNOR | 182 | |

| PART II. JERUSALEM AND THE WAY THITHER | 205 | |

| VI. | Inns | 240 |

| VII. | On the Road | 284 |

| VIII. | The Purse | 313 |

| Special References | 381 | |

| Bibliography | 389 | |

| Index | 407 | |

| Departure of a Tourist | Frontispiece | |

| (British Museum MS. Egerton 1222, fol. 44.) | ||

| A Pilgrimage Scene | 18 | |

| From a woodcut by Michael Ostendorfer (1519-1559) or perhaps by his master, Albrecht Altdorfer. Both lived at Regensburg, where the scene of this picture is laid, this shrine of Our Lady of Regensburg being a regular pilgrimage centre (British Museum). | ||

| The Cheapest Way | 22 | |

| "Les Bohémiens" (no. 1) by Jacques Callot (1594-1635). The artist ran away from home to Italy when a youngster and fell in with company of this kind on the road. The second state (1633; British Museum) has been reproduced in preference to the first as being in no way inferior and having the advantage of the verses appended to them by another traveller of the time, the Abbé de Marolles. | ||

| A Typical Town-Plan | 52 | |

| Map of Venice, illustrating especially the disregard of scale. From H. de Beauveau's "Relation journalière," 1615. | ||

| A Typical Map | 54 | |

| Part of Flanders, from Matthew Quadt's "Geographisch Handtbuch," 1600. Illustrates the approximateness of detail and the absence of roads, especially as contrasted with the indications of waterways. But it must be noted that cartography made as great advances during the period here dealt with as surgery during the nineteenth century. | ||

| A Channel Passage-Boat | 64[x] | |

| From Münster's "Cosmographie," 1575 (ii. 865—part of the map of Germany). | ||

| Ship for a Long-Distance Voyage | 72 | |

| Dutch vessel, showing the open cabins at the stern in which Moryson preferred to sleep. From J. Fürtenbach's "Architectura Navalis," 1629. | ||

| Lock between Bologna and Ferrara | 82 | |

| From J. Fürtenbach's "Newes Itinerarium Italiæ," 1627. There were nine of these in thirty-five miles. Fürtenbach's sketch shows an oval basin as seen from above, with lock-gates at the down-stream end only. He gives its measurements as large enough for three vessels, with walls twenty ells high. | ||

| Gate of St. George, Antwerp | 122 | |

| The gate as it appeared about the middle of the sixteenth century (Peter Bruegel the elder: Bibl. Royale de Belgique), showing also the long covered waggon which was practically the only land conveyance in use, apart from litters. | ||

| Venetian Mountebanks | 134 | |

| Painted between 1573 and 1579; from a Stammbuch (British Museum MS. Egerton 1191). Concerning these mountebanks the French traveller Villamont writes in 1588, 'And if it happens that they [i.e. the 'sights' of Venice] bore you, go and look at the 'charlatans' in St. Mark's Place, mounted on platforms, enlarging on the virtues of their wares, with musicians by their side.' | ||

| Public Executions | 136 | |

| [xi]The "Supplicium Sceleri Froenum" of Jacques Callot (1592-1635). The first state of the etching seems to be unobtainable for reproduction, this being from a photograph (the only one hitherto reproduced?) of one of the better copies of the second state, almost equally rare in a good condition (Dresden Museum). | ||

| Dangers of the Northern Seas | 156 | |

| According to Münster's "Cosmographie" 1575 (ii. 1724). | ||

| At Montserrat | 164 | |

| Montserrat and its hermitages, with the Madonna and Child in the foreground and two pilgrims. From British Museum Harleian MS. 3822, folio 596. The two pilgrims are obviously the writer of the manuscript, Diego Cuelbis, of Leipzig, and his companion, Joel Koris. They visited Montserrat in 1599. | ||

| An Irish Dinner | 178 | |

| Referring more particularly to the MacSweynes, "whose usages," says the author, John Derricke, in his "Image of Irelande," 1581, "I beheld after the fashion there set down." From the copy (the only complete one known) in the Drummond Collection in the Library of the University of Edinburgh. The cut also illustrates the contrasts in Irish life as seen by the foreigner, referred to in the chapter on Ireland. | ||

| An Example of Turkish Fine Art | 190 | |

| Miniature illustrating some of the characteristics of Turkish art which Della Valle and other contemporary travellers prized so highly. The brilliant colouring of the original throws into relief much detail in the flowers which is necessarily lost in reproduction. (From Brit. Mus. Add. MS. 15,153; a copy of the Turkish translation of the Fables of Bidpai, dated 1589.) | ||

| Pilgrims leaving Jaffa for Jerusalem, 1581 | 210 | |

| From the MS. of Sébastien Werro, curé of Fribourg (Bibl. de la Société Economique de Fribourg). Showing also the fort at Jaffa, the caves in which pilgrims had to lodge until permission was given to depart, and the peremptory methods of the Turks when a pilgrim got out of the line of march.[xii] | ||

| At Mount Sinai | 222 | |

| From Christopher Fürer's "Itinerarium" (1566). | ||

| Arms of a Jerusalem Pilgrim | 238 | |

| Arms of Sébastien Werro, curé of Fribourg, Switzerland, surmounted by the arms of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, showing that he received that knighthood on the occasion of his pilgrimage thither, 1581. The title-page of the account of his journey written by himself (Bibl. de la Société Economique de Fribourg). | ||

| Two German Kitchens | 254 | |

| The 'fat' and the 'lean.' Plates 58 and 63 of J. T. de Bry's "Proscenium Vitæ Humanæ" ("Emblemata Sæcularia"). From the copy of the first edition (1596) in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. | ||

| German Bathing-Places | 268 | |

| From Münster's Cosmography; two of the woodcuts are from the French edition of 1575 (ii. 1020-21), the other from the Latin edition of 1550. Visitors to Berlin will find the subject more artistically illustrated by the "Jugendbrunnen" of Lucas Cranach the younger, too large for reproduction here to do it justice. | ||

| The Red Gate, Antwerp | 272 | |

| As it was about the middle of the sixteenth century (plate I of Peter Breugel the elder's "Prædiorum Villarum ... Icones"; Bibl. Royale de Belgique), showing also the inn which, according to the custom so convenient to late arrivals, was usually to be found outside the gate of a town. | ||

| A Main Road in Alsace | 284 | |

| Showing ruts and loose stones. From Münster's "Cosmographia" (1550; p. 455). | ||

| A Sign-Post[xiii] | 294 | |

| From the 1570 edition of Barclay's translation of Brandt's "Ship of Fools." | ||

| "The hande whiche men unto a crosse do nayle Shewyth the way ofte to a man wandrynge Which by the same his right way can nat fayle." |

||

| Benighted 'Sight'-seers | 312 | |

| From Josse de Damhouder's "Praxis Rerum Criminalium," 1554. | ||

| A Passenger-Boat from Padua | 328 | |

| From the "Stammbuch" (1578-83) of Gregory Amman in the Landesbibliothek, Cassel. | ||

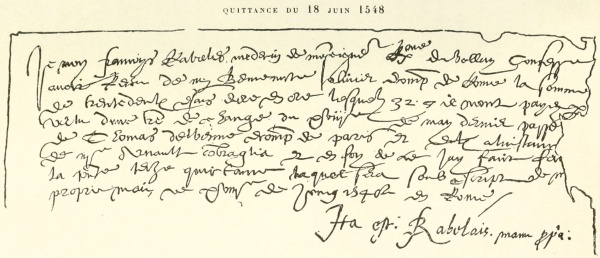

| Rabelais receives some Money | 342 | |

| Rabelais' receipt for money received by him against a bill of exchange such as travellers used. Photographed (with M. Heulhard's transcription) from the latter's "Rabelais, ses Voyages, et son Exil." | ||

| Lithgow in Trouble | 348 | |

| From the 1632 edition of his "Rare Adventures." | ||

| Travellers attacked by Robbers | 354 | |

| No. 7 of Jacques Callot's "Misères de la Guerre"; a photograph of the British Museum copy of the second impression (1633). The second state has been chosen in preference to the first, as including the verses of the Abbé de Marolles, himself a traveller; the clearness of the etching not having suffered in the second impression. | ||

| "Wolves" | 356 | |

| Another wood-cut from Derricke's "Image of Irelande," or rather, part of one, the size of the original. It represents Derricke's best wishes for Rory Oge, the 'rebel,' but is none the less applicable generally. | ||

| A Souvenir | 360[xiv] | |

| A letter which was on the way between Venice and London in October, 1606, when the bearer was attacked by robbers in Lorraine, showing the tears and damp-stains it received in consequence. The letter is from Sir Henry Wotton, then ambassador in Venice; it was picked up and forwarded to Henry IV of France, who sent it on to London. It is now in the Public Records Office, No. 74 in Bundle 3 of the State Papers, Foreign (Venetian). The bearer, Rowland Woodward, was paid £60 on Feb. 2, 1608, as compensation and for doctor's expenses, but had not fully recovered from his injuries by 1625. (Cf. L. P. Smith's "Life and Letters of Sir Henry Wotton," i, 325-8, 365 note, and ii. 481.) | ||

| A Scholar Traveller | 390 | |

| François de Maulde (1556-97); portrait by J. Sadeler

(Bibl. Royale de Belgique). He was only about thirty

when this portrait was done, but his sufferings as a traveller

(see Bibliography) would alone account for his weary

look. The inscription belonging to it runs:— "Tristia sive secunda fluant, in utrumque parato Dulce mihi in libris vivere, dulce mori est." |

||

TOURING IN 1600

"Che Dio voglia che V. S. abbia pazienza di leggerla tutta."

Pietro della Valle, "Il Pellegrino."

But thus you see we maintain a trade, not for gold, silver, nor jewels; nor for silks; nor for spices; nor any other commodity of matter; but only for God's first creature, which was Light; to have Light (I say), of the growth of all parts of the world ... we have twelve that sail into foreign countries, ... who bring us the books, and abstracts and patterns of experiments of all other parts. These we call Merchants of Light.

F. Bacon (1561-1626), New Atlantis.

First, M. de Montaigne.—When Montaigne found himself feeling old and ill, in 1580, he made up his mind to try the baths of Germany and Italy. So he set out; and returned in 1581. And sometimes the baths did him good and sometimes they made no difference; but the journeying never failed to do what the baths were meant for. He always, he says, found forgetfulness of his age and infirmities in travelling. However restless at night, he was alert in the morning, if the morning meant starting for somewhere fresh. Compared with Montaigne at home, Montaigne abroad never got tired or fretful; always in good spirits, always interested in everything, [4]and ready for a talk with the first man he met. And when his companions suggested that they would like to get to the journey's end, and that the longest way round, which he preferred, had its disadvantages, especially when it was a bye-road leading back to the place they started from, he would say, that he never set out for anywhere particular; that he had not gone out of the way, because his way lay through unfamiliar places, and the only place he wished to avoid was where he had been before or where he had to stop. And that he felt as one who was reading some delightful tale and dreaded to come upon the last page.

So, no doubt, felt Fynes Moryson, for much of his life he spent either in travelling or in writing the record of it. Starting in 1591, when he was twenty-five, he passed through Germany, the Low Countries, Denmark, Poland, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, spending his winters at Leipzig, Leyden, Padua, and Venice, learning the languages so thoroughly as to be able to disguise his nationality at will. Returning through France, he was robbed, and consequently reached home so disreputable-looking that the servant took him for a burglar. He found his brother planning a journey to Jerusalem. On the 29th of November, 1595, they set out, and on July 10, 1597, he was back in London, in appearance again so strange that the Dogberry of Aldersgate Street wrote him down for a Jesuit. But he returned alone: his brother[5] Henry, twenty-six years old and not strong, fell ill at Aleppo, how ill no one knew till too late, and near Iskenderún he died in his brother's arms, while the Turks stood round, jeering and thieving. Fynes buried him there with stones above him to keep off the jackals, and an epitaph which a later traveller by chance has preserved.[1]

Fynes himself hurried home and never crossed the Channel again. But he extended his knowledge of Great Britain by a visit to Scotland, and by accompanying Sir Charles Blount during the latter's conquest of Ireland. Then he settled down to write all he knew and could get to know about the countries he had seen, and wrote at such length that no one till quite recently has had the courage to reprint his account, although what he printed was by no means all that he wrote. For this reason his work has remained practically unused, even by writers whom it specially concerns. It must form the basis of any description of the countries he saw, at any rate, as seen by a foreigner, going, as he does, more into detail than any one else, and being a thoroughly fair-minded, level-headed, and well-educated man, whose knowledge was the result of experience. His day was not the day of the 'Grand Tourist,' whose habit [6]it was to disguise single facts as general statements, and others' general statements as his own experiences.

Yet however irreplaceable may be Montaigne's subjectivity and Moryson's objectivity, it is desirable to find some one who combines both. Such a one is Pietro della Valle, of Naples and Rome. He is the impersonation of contemporary Italy at its best; of, to use his own phrase, "quella civiltà di vivere e quello splendore all' italiana," and to read his letters is to realise, as in no other way can be so readily realised, the reason why Italy held the position she did in the ideas of sixteenth-century people. If you separate the various characteristics that account for much of the attractiveness of his writings; the interest in things small and great, without triviality or ponderousness; the ability to write, combined with entire freedom from affectation; the lovableness of his Italian and a charm of phrase apart from his Italian, which might even, perhaps, survive translation; learning without arrogance and hand in hand with observation; and refinement and virility living in him as a single quality—if you isolate these, there still remains something to distinguish him from contemporary travellers, the product of gifts and character, it is true, but only of gifts and character as moulded by contact from birth with the best of a splendid civilisation, of which all the gentlemen of Europe[7] were students, but none but natives graduates.

Still, in one respect, contemporary travellers may claim he has taken an unfair advantage. Not one of them has a romantic love-story as a background to his journeyings; Della Valle has two. After a twelve years' courtship at home, his intended bride was given by her parents to some one else. This was the cause of his wanderings. At San Marcellino at Naples, a mass was sung and the nuns prayed, the little golden pilgrim's staff he wore round his neck was blessed, and a vow made by him never to take it off until he had visited the Holy Sepulchre.

Thus he became Pietro della Valle, "Il Pellegrino" (the Pilgrim); and started. Venice, Constantinople, Cairo, Jerusalem, Damascus, was his route; but his next letter thereafter is "from my tent in the desert": he has disappeared over the tourist horizon, and become a traveller on the grand scale. But he returns, and has much to say on the way back. Meanwhile, in Babylon, he has met another lady-love, Maani Gioerida, eighteen years old, daughter of an Assyrian father and an Armenian mother. Marriage with her was soon followed by her death; for the remaining four years of his wanderings he carried her body with him, laying it to rest in the end in his family tomb: and married again, this time the girl who had attended his first wife, alive and dead, Maria [8]Tinatin di Ziba, a Georgian. And with her he lived happy ever after, and by her had fourteen sons.

Another type of traveller is the philosopher philosophizing. Sir Henry Blount set four particular aims before himself when he started for southeastern Europe with the intention of increasing his knowledge of things human, choosing the southeast because the west too closely resembled England. He went to note, first, the characteristics of "the religion, manners, and policy of the Turks" in so far as these threw light on the question whether they were, as reputed, barbarous, or possessed of a different variety of civilisation. Secondly, to satisfy the interest he felt in the subject-races, especially Jews; thirdly, to study the Turkish army about to set out for Poland; and fourthly, Cairo, which being the largest city existing, or on record, had problems of its own whose solutions he wished to note, much as foreigners might come to study London County Council doings now. This was in 1634.

But besides those who were born travellers and those who achieved travel, there were those who had travel thrust upon them; Thomas Dallam, for instance. Dallam was the master organ-builder of Elizabethan England. When, therefore, the Queen wished to send such a present to the Grand Turk as should assure her outshining all other sovereigns in his eyes and assist the Levant Company (who probably paid for it) in [9]securing further privileges, an organ was the present, and Dallam had to make it and to take it. In 1599 he set out, and in 1600 praised God for his return. He, too, was an excellent Englishman: shrewd, interested, and interesting; and with an ability to express himself just abreast of his thinking faculty. His organ was a marvellous creation; played chimes, and song-tunes by itself, had two dummy-men on it who fanfared on silver trumpets, and, above, an imitation holly-bush filled with mechanical birds which sang and shook their wings. The Grand Turk sent for Dallam to play on it, which he did rather nervously, having been warned that it meant death to touch the Signor, and the latter sat so near behind him that "I touched his knee with my breeches.... He sat so right behind me that he could not see what I did, therefore he stood up, but in his rising from his chair, he gave me a thrust forward, which he could not otherwise do, he sat so near me: but I thought he had been drawing his sword to cut off my head."

The organ was so great a success that Dallam became a favoured man. One attendant even let him look in at a grating through which he saw thirty of the girls of the harem playing ball, each wearing a chain of pearls round the neck, a ring of gold round the ankle, velvet slippers, a small cap of cloth of gold, breeches of the finest muslin, and a scarlet satin jacket.

Dallam was more in favour than he liked, for he was urged to settle there. "I answered them that I had a wife and children in England who did expect my return, though indeed I had neither wife nor children, yet to excuse myself I made them that answer."

Besides the business man who became a tourist without knowing it, there were the tourists who became so because home was too hot for them. Of their number was William Lithgow, whose "Rare Adventures" is the record of nineteen years' travel, ended in 1620 by the severity of the torture he endured in Spain through being taken for a spy. Although fifty years of age when he started writing his account, a fair sample of his style is,—"Here in Argos I had the ground to be a pillow, and the world-wide fields to be a chamber, the whirling windy skies to be a roof to my winter-blasted lodging, the humid vapours of cold Nocturna to accompany the unwished-for bed of my repose." And this was accompanied by so much second-hand history and doggerel that the printer rebelled and saved us from much more of it. The trustworthiness of his facts may be gauged by his stating as the result of his personal experience that Scotland is one hundred and twenty miles longer than England. On the other hand, he visited more places in Europe than any other one tourist, besides having some experience of Palestine and North Africa; and what he wrote he [11]wrote after he had seen all that he did see. His comparisons are, therefore, worth attention, and these and the personal experiences which his verbiage has not crowded out of his book give it a permanent value and interest to those who have the patience to find them.

All this while we are forgetting the ladies; very few in number, but three at least possessing personality,—two princesses and an ambassador's wife. Princess number one was the eldest daughter of Philip II of Spain, the Infanta Doña Clara Eugenia, who crossed Europe with her husband, to take up the government of the Low Countries, in 1599, and wrote a long letter to her brother about the journey from Milan to Brussels, bright and pithy, one of the most readable and sensible letters that remain to us from the sixteenth century. Princess number two is the daughter of a king of Sweden, who had trouble in finding a husband for Princess Cecily, inasmuch as she would marry no one who would not promise to take her to England within a year from the wedding day; for the great desire of her life was to see Queen Elizabeth. A marquis of Baden accepted the condition, and on November 12, 1564, they started, by which time she had spent four years learning English and could speak it well. The voyage took ten months, the winter was a severe one, and much of their way lay through countries whose kings were hostile to her father and the inhabitants to every [12]stranger. Leaving Stockholm while her relatives expressed their opinion about her journey by lamentations and fainting-fits, she crossed to Finland in a storm, in which the pilot lost heart to the extent of pointing out the rock on which they were going to be shipwrecked. Finland they left in four days, to escape starvation, during another storm; crossed to Lithuania; thence by land through Poland, North Germany, and Flanders, to Calais. Even from here it was not plain sailing, in any sense of the words; the sea was high when she started; all were sick ("with the cruel surges of the water and the rolling of the unsavoury ship"), except herself, standing on the hatches, looking towards England. But it proved impossible to get into Dover and they had to turn back. "'Alas!' quoth she, 'now must I needs be sick, both in body and in mind,' and therewith taking her cabin, waxed wonderful sick." A second time they tried; and again all were sick but herself; "she sitting always upon the hatches, passed the time in singing the English psalms of David after the English note and ditty." But again they had to turn back and again that made her sick, so sick that they thought she was going to be confined, for she had become pregnant about the time of her starting. A third attempt was successful; and on September 11, 1565, she arrived at Bedford House, Strand; on the 14th Queen Elizabeth arrived there, too, to see her; and on the 15th came the baby. [13]This story ought to end like Della Valle's, that she lived happy ever after; but that cannot truthfully be said, because of what is recorded about Princess Cecily and certain unpaid London tradesmen. Much more would there be to say of her as a tourist, had she written an autobiography; for the rest of her life she continued travelling, spending all her own money on it and much of other people's.

The third, the ambassador's wife, is Ann, Lady Fanshawe. Her travels belong, strictly speaking, to dates just outside the limits (1542-1642) with which this book is concerned, but for all practical purposes may be referred to with little reserve. Her experience was great, for her journeys were even more numerous than her pregnancies, which numbered eighteen; and being cheerful, clear-headed, and sincere in no ordinary measure, her "Memoirs" are almost as excellent a record of travel as of character.

It is a matter for regret that her husband, Sir Richard, has not left us an account of his own, but in this he resembles practically all his kind. There is Sir Robert Sherley, who went ambassador to two Emperors, two Popes, twice to Spain, twice to Poland, once to Russia, twice to Persia: yet of Sir Robert Sherley as tourist, we know next to nothing. So also of Sir Paul Pindar, who says in a letter that he has had eighteen years' experience of Italy; and De Foix, a man greatly gifted, who wished to serve his country as far as possible distant[14] from its Valois Kings, and consequently chose a series of embassies as an honourable, useful form of self-exile. Yet of these last two and others there remains some record by means of men who accompanied them. Part of the travels of Peter Mundy, whose name will often recur, happened in the train of the former; and when De Thou, the historian, paid the visit to Italy which he recounts in his autobiography, it was with De Foix that he went.

Among the exceptions, most noticeable is Augier Ghiselin de Busbecq, a Fleming. After representing the Emperor in England at the wedding of Philip and Mary, he was sent to Constantinople (1556-1562), and afterwards to France. His letters from France that have been preserved are semi-official; of minor interest compared with those from Constantinople, which, not meant for publication but addressed to friends who were worthy of them, in time became printed. They belong to the literature of middle age, that which is written by men of fine character and fine education when successful issues out of many trials have made them wise and left them young. A many-sided man: the library at Vienna is the richer for his presents to the Emperor; many are the stories he tells of the wild animals he kept to while away the hours of the imprisonment which he, ambassador as he was, had to endure; the introducer into Europe of lilac, tulips, and [15]syringa; a collector of coins when such an occupation was not usual as a hobby. His opportunities, indeed, were such as occur no more; in Asia Minor coins one thousand years old were in daily use as weights; and yet Busbecq missed one chance, for a brazier to whom he was referred regretted he had not met him a few days earlier, when he had had a vessel full of old coins which he had just melted down to make kettles.

Turning from the personalities to the causes of travel, we find that the class to which Busbecq belonged, that of resident ambassador, was of recent growth, and that it, and the tendencies of which it is one symptom, are responsible for creating the whole of the motives and the facilities for travel which characterise journeyings of this time as something different in kind from those which preceded them. The custom of maintaining resident representatives was developed in Italy during the fifteenth century, but it did not spread to the rest of civilised Europe till near the beginning of the next; German research, indeed, has even narrowed down the dates within which it established itself as an international system to 1494-1497.[2] The change was partly due to the consolidation of sovereignties, which increased the distances to be traversed between neighbour-princes, partly to the insight of the three great rulers who achieved the consolidations,—Ferdinand of Aragon, Louis XI, and Henry VII, who [16]abandoned the idea of force and isolation as the only possible policies, and attempted to gain the advantages, and avoid the disadvantages, of both by means of ambassadors. Henry VII regarded them as in no way differing from spies; the most efficient kind of spies, from the point of view of the sender; and unavoidable, from that of the receiver. The latter's only remedy, Henry VII thought, was to send two for every one received. This alone, regarded, as it must be, considering who the speaker was, as indicating what the practice of the future would be, suffices to explain, even to prove, a great increase in diplomatic movements. But what further compels the deduction is that the foregoing is reported by Comines, who was probably, next to Francesco Guicciardini, the most frequently read historian throughout the sixteenth century.

Side by side with these official spies was the secret service; bound to grow in proportion to the increase among the former, implying a certain cosmopolitanism in its members, which, again, implies touring. This class of tourists is naturally the least communicative of all, but so far as England alone is concerned, if the history of the growth of the English spy-system between Thomas and Oliver Cromwell ever comes to be written, it is bound to reveal an enormous number of men, continually on the move for such purposes, or qualifying themselves for secret service by previous[17] travel. And while there is a certain amount of information concerning tourists and touring to be gathered, in scraps, among State Papers which concern spies as spies, there is a great deal available, often first-hand, from them during this period of probation. Many, also, would be termed spies by their enemies and news-writers by their friends; persons who are abroad for some other, more or less genuine, reason, whose information was very welcome to those at home in the absence of newspapers, and was often paid for by politicians who could acquire a greater hold on the attention of those in power by means of knowledge which was exclusive during a period when the Foreign Office of a government existed in a far less definitely organised form than at present. It was in the course of such a mission that Edmund Spenser saw most of Europe and gained that intimate knowledge of contemporary politics which gives his poems a value which would have been more generally recognised had not their value as poetry overshadowed other merits. The traveller, then, still fulfilled what had been his chief use to humanity in mediæval times, that of a "bearer of tydynges," as Chaucer insists often enough in his "House of Fame."

It is worth while turning back to Chaucer's time to see how far the classes of travellers then existing have their counterparts in 1600, and how far not. Omitting students and artizans, as not [18]varying, the types to be met on the road then may be collected into those of commerce, pilgrimage, vagabondage, and knight-errantry.

With regard to commerce, it may safely be guessed that the absence of the modern inventions for communication at a distance implied, in 1600 as in Chaucer's day, a greater proportional number of journeys in person than at present: and the enormous extension of commerce involved in the discoveries of sea-routes must have involved an increase in commercial traffic within Europe. As for the particular forms of trade that were responsible for taking men away from their homes, within the limits of Europe, it would probably be found, if statistics were possible, that dried fish came first, with wine and corn bracketed second. The Roman Catholic fast-days had produced a habit of eating dried fish which was not to be shaken off, in the strictest Protestant quarters, directly; and it was largely used for provisioning armies.

The second class of mediæval traveller, the pilgrim, is often in evidence about 1600, usually indirect evidence; the pilgrim who is nothing but pilgrim leaves practically no detailed record of himself except when he goes to Jerusalem. Yet Evelyn was told at Rome that during the year of Jubilee, 1600, twenty-five thousand five hundred women visitors were registered at the pilgrims' hospice of the Holy Trinity there, and four hundred[19] and forty thousand men. Also, one who was at Montserrat in 1599, was told that six hundred pilgrims dined there every day, and at high festivals between three thousand and four thousand; while another (1619) learnt that whereas the monks' income from their thirty-seven estates stood at nine thousand scudi (say, thirteen thousand pounds at to-day's values) annually, they spent seven times that amount, the balance being derived from the sale of sanctified articles or from gifts.[3] On the whole, however, a decrease must be presupposed during this period on account of the cessation of pilgrimage among the Protestant half of Europe. Moreover, the kind of journeying which is specially characteristic of this period incidentally tended to further Protestant ideas and discredit pilgrimage. For pilgrimage was, of course, towards some relic. Now relics which mutually excluded each other's genuineness, such as two heads of one saint, were not likely to be met with on the same pilgrim route: the establishment of one such on a given route would hinder the establishment of a second for financial, as well as devotional, reasons. But when a believer travelled for diplomatic or educational purposes, his direction was quite as likely to lead across pilgrim routes, as along them. In which case he would be morally certain to come across these mutually exclusive relics, on one and the same journey, and the doubts thus started [20]might be cumulative in their results.[4] On the other hand the very fact of opposition stimulated pilgrim zeal among the orthodox, as, e. g., to the still flourishing shrine of Notre Dame des Ardilliers near Saumur, as a result of Saumur itself becoming a headquarters of the "Reformed" creed. There abided of course the permanent features of life which make pilgrimage as deep-rooted as the love of children, and one of the epidemics of pilgrimage that occur periodically burst out in France about 1585, so Busbecq writes. Whole villages of people clothed themselves in white linen, took crosses and went off to some shrine two or three days' journey away. The special cause of this epidemic may perhaps be sought in the pilgrimage to Our Lady of Chartres by their queen, in 1582, to beg for relief from her barrenness. One incident of this journey ought not to be left buried in the Calendar of Foreign State Papers, the only place where it has hitherto been printed. On being told why the queen was going thither, a countrywoman said, "Alas! Madame is too late; the good priest who used to make the children has just died."

An example of the pilgrim we have already met in Della Valle. Bartholomew Sastrow in his autobiography reveals a man travelling in search of work, a very unpleasant man, perhaps, but so strikingly true a picture of the every-day life and every-day thought of a lower middle-class man of [21]the sixteenth century as not to be surpassed for any other century, past, present, or future, not even among autobiographies.

But for the man who is trying to avoid work, the third of the mediæval types, the vagabond, it would be out of place to select an individual to stand for the class in Renascence days, seeing that it became a stock literary type; vagabondage in general being epitomized for the time in the Spanish picaro. The picaro was one who saw much of the seamy side of life and remembered it with pleasure—it was all life and the true picaro was in love with life. The only enemy he had permanently was civilisation; yet he and it became reconciled in his old age: a picaro who grew old ceased to be a picaro. Meanwhile he was always forgiving civilisation, and being forgiven; both had equal need of forgiveness. Yet there is one picaro characteristic hard to overlook—his passion for being dull at great length when he drops into print: Lazarillo de Tormes and Gil Bias being the only ones of whom it may be said that from a reader's standpoint they were all that they should have been and nothing that they should not. The rest, when met between the covers of a book, resemble the parson whom one of themselves, Quevedo's Pablos, caught up on the way to Madrid and whom he hardly prevented from reciting his verses on St. Ursula and her eleven thousand virgins, fifty octavetts to each virgin; even then [22]he could not escape a comedy containing more scenes than there were days in a Jerusalem pilgrimage, besides five quires concerning Noah's Ark. This same Pablos explains incidentally what his kind talked about to chance companions on the road, for meeting another making for Segovia they fell into "la conversacion propia de picaros." Whether the Turk was on the downhill and how strong was the king: how the Holy Land might be reconquered, and likewise Algiers: party politics were then discussed and afterwards the management of the rebellious Low Countries. There were, too, picaros of high degree, but these were all men of war, whereas nothing but hunger made an ordinary picaro fight. High and low, however, had this in common, that they preferred living at others' expense to working, and consequently shifted their lodgings as often as any other class of tourist, in deference to local opinion.

Of the fourth mediæval type, the knight-errant, it is hard to say whether it was extinct or not: all depends on the extent to which the knight-errant is idealised. It is certainly true in this degree, that contemporary fiction must be reckoned as a cause of travel. Don Quixote is not to be ignored as a traveller and he was not alone. The first Earl of Cork's eldest son was so affected by the romances that the "roving wildness of his thoughts" which they brought about was only partially cured by continual extraction of square and [23]cube roots. But perhaps the knight-errant of this date is better identified with the picaro of high degree, and as such the class may be exemplified by Don Alonzo de Guzman, the first chapter of whose autobiography gives a better insight into the psychology, and life on the road, of the picaro than the whole flood of nineteenth-century comment on the subject. At the age of eighteen he found himself with no father, no money, and a mother pious but talkative; after having provided for his needs for a while by marriage, he left home with a horse, a mule, a bed, and sixty ducats. And though what follows belongs more to the history of lying than the history of the world, it throws side-lights. And at any rate, any excuse is good enough to turn to it, for Don Alonzo has much in common with Benvenuto Cellini.

Now we have passed beyond the mediæval types and come to such as are somewhat more prominent in this, than in the previous, centuries. Exiles, for instance. The economic changes that took place during the sixteenth century made it increasingly difficult for the equivalents for Chancellors of the Exchequer to meet the yearly deficits. The legal authorities were therefore called upon to assist, and a working arrangement was established in practically all European countries whereby the political ferment of the time was taken advantage of for the betterment of the finances. Instead of the slow process and meagre [24]results of waiting for death-duties, a man of wealth suffered premature civil death, or was harried into civil suicide. He was exiled, or fled: he had become a tourist.

Inseparable from political is religious self-exile. What happened very often in England was this. A youngster is seized with that belief in the likelihood of an ideal life elsewhere and that desire for a change, which are characteristic of the age of twenty. The theological cast of the age gives the former a religious bias. He escapes. After a time it seems to him that human characteristics have the upper hand of the apostolic, even in Roman Catholics, to a greater extent than he once believed, and that he would like to go home. He lands, is questioned by the Mayor, reported on to the Privy Council, in which report his experiences are to be found summarised.

One class of men, however, which might be expected to provide many examples, is for the most part absent,—missionaries,—occupied at home converting each other at this date, or re-converting themselves. The chief, in fact, the Jesuits, were confined each one to his nation by order, and only in respect of their early training days do they appear as foreigners abroad. Acknowledgements are due, on the other hand, for information received, to captives set free, soldiers, artists, herbalists, antiquaries, and even to those who, so far as we know, only looked on, like Shakespeare; and [25]to many others led abroad by special reasons, such as the Italian Marquis who felt it necessary for him to have a long holiday after the privations of Lent.

But with all these varieties of tourist, we still have not come to the Average Tourist. The type is extinct, killed by reference-books, telegraphy, and democracy. For the Average Tourist left his fatherland to get information which he could not get at home, and he wanted this information because he was a junior member of the aristocracy, at that time the governing class more exclusively than at present. In feudal days isolation was, comparatively, taken for granted, and the fact of that voluntary isolation implied many hindrances to touring. The need of acquiring information of every kind that affected political action had been therefore less realised and the difficulty of acquiring it greater. These years near 1600 are the years of transition, transition to a custom for travellers to

Herein lies the unity of subject of this book; not in its concern with a given class of experiences [26]during a given period. Roughly speaking, in the two half-centuries preceding and succeeding the year 1600, the practice of the upper classes of sending sons abroad as part of their education became successively an experiment, a custom, and, finally, a system. By the middle of the seventeenth century this system had become a thoroughly set system, and the "Grand Tour" a topic for hack-writers. Of the latter, James Howell was the first. His "Instructions for Foreign Travel" (1642) may serve to date the beginning of "Grand Touring" in the modern sense of the phrase, while the publication of Andrew Boorde's "Introduction of Knowledge" a century earlier, does the same for this preceding period, that of the development of travel as a means of education.

Delimiting the movement by means of English books suggests that it was a merely English movement, but it was in fact European, though true of the different countries in varying degrees. The increase of diplomatic journeys,[6], already mentioned, the core of this development and its chief instrument, was common to all divisions of Europe in proportion to the degree of the civilisation attained. In the Empire and Poland the custom grew up less suddenly; it had begun earlier. In Italy, it began later, since it was not till later that there was much for an Italian to learn that he could not learn better at home. Sir Henry Wotton[7] noted in 1603 that travelling was coming into [27]fashion among the young nobles of Venice. In France, an early beginning was broken off by the civil wars, not to start afresh till Henry IV's sovereignty was established. As for Spaniards and Portuguese, they alone had dominions over-sea to attend to.

In England, on the other hand, political reversals being at once frequent, thorough, and peaceable, migrations were very common and usually short. That touring would result from migration was certain, because it familiarised English people with the attractions and the affairs of the continent and with the uses of that familiarity, and established communications. Other special causes existed, too, truisms concerning which are so plentiful that there is no need to repeat them here.

But the certainty of the change did not prevent it being slow. Andrew Boorde, who knew Europe thoroughly, found hardly any of his countrymen abroad except students and merchants, and for the following half century it is the tendency rather than the fact that may be noted, as indicated, for example, by Sir Philip Sidney, who started in 1572, writing later to his brother that "a great number of us never thought in ourselves why we went, but a certain tickling humour to do as other men had done." In 1578 Florio could still write in one of his Italian-English dialogues published in London:[8] "'Englishmen, go they through the world?' 'Yea some, but few.'" Yet in 1592 and [28]again in 1595 the Pope complained about the number of English heretics allowed at Venice,[9] and in 1615 an Englishman, George Sandys, leaves out of his travel-book everything relating to places north of Venice, such being, he says, "daily surveyed and exactly related." Three years earlier James I's Ambassador at Venice writes[10] to the Doge that there are more than seventy English in Venice whereas "formerly" there had been four or five; and when he adds that there are not more than ten in the rest of Italy it must be remembered that he is making out a case and even then refers to Protestants only: between 1579 and 1603, three hundred and fifty Englishmen had been received into the English College at Rome.[11]

The development, then, of the English tourist may be synchronised with the rise of the English Drama and the expansion of English Commerce. In other words, the preparation for it came before the failure of the Spanish Armada; the actuality directly afterwards. But it could not have followed the course it did except in conjunction with wider causes, which emphasise its place as but part of a European movement. These may be sought in (1) the slight, but definite, advance in civilisation which made people more accessible to the ideas which peace fosters; (2) the greater area over which peace prevailed round about the year 1600: (3) the increase in centralisation in government, which decreased the obstacles in the way of [29]the traveller, and increased the attractiveness of particular points, i.e., where the courts were held.

At the same time the increase in touring which really took place would be greatly over-estimated if one considered the evidence of bibliography as all-sufficient. Almost all that the latter proves is an increase in writing about it, due to the greatly increased demand for the written word which was the outcome of printing. Morelli, in his essay[12] on little-known Venetian travellers, quotes Giosaffate Barbaro as writing in 1487, "I have experienced and seen much that would probably be accounted rubbish by those who have, so to speak, never been outside Venice, by reason that such things are not customary there. And this has been the chief reason for my never having cared to write of what I have seen, nor even to speak much thereof." Yet by 1600 there were probably few countries in Europe in which recent accounts of the regions visited by Barbaro could not be read in the vernacular, accounts out of which some one expected to see a profit. Indications, on the contrary, of enormous numbers leaving home may be found in this one fact; that the names are known of twelve hundred Germans who passed beyond the limits of civilised Christendom during the sixteenth century.[13] What must then be the number of Europeans, ascertainable and otherwise, who were going about Europe then?

As regards the Average Tourist, however, we [30]are not left to our imagination. He is often to be found in person, young, rich, abroad to learn. Yet—why should he, rather than his contemporaries of the lower classes, need teaching? The answer will come of its own accord if we stop to consider the similarities and divergences existent between the Jesuits and the Salvation Army. Both are the outcome of the same form of human energy, that of Christianity militant against present-day evils; it is circumstances that have caused the divergence. The Jesuits were as keen at first for social reform as the Salvation Army have become; the Salvation Army used to be as much preoccupied with theology as the Jesuits. In details the resemblance is more picturesque without being any more accidental. The Salvation Army describe themselves after the fashion of the Papal title of "servus servorum Dei," as the "servants of all"; and the first thing that Loyola did when his associates insisted on his adopting the same title that "General" Booth has assumed, was to go downstairs and do the cooking. The two societies with one and the same root-idea essentially, have been drawn into ministering to the lower class in the nineteenth century and the upper class three hundred years earlier: the identity of spirit consisting in the class that was ministered to being that which possessed the greatest potentialities and the greatest needs.[14] And in all the prescribed occupations of the Average Tourist we shall find this [31]implied, that the future of his country depended on the use he made of his tour.

Let us take two specimens; one in the rough, the other in the finished, state: No. 1 shall be John Lauder of Fountainhall; No. 2, the Duc de Rohan. The former's diary is not to be equalled for the insight it gives into the development of the mind of the fledgling-dignitary abroad; not a pleasant picture always, not the evolution of a mother's treasure into an omniscient angel, but of a male Scot of nineteen into the early stages of a man of this wicked world; but—it happened. We note his language becoming decidedly coarser and an introduction to Rabelais' works not improving matters. Still, the former would have happened at home, only in a narrower circle; and for Rabelais, who that has read him does not know the other side? Then, he did not always work as a good boy should: he was studying law at Poictiers, and a German who was there twenty years earlier tells us that at Poictiers there were so many students that those who wanted to work retired to the neighbouring St. Jean d'Angely. Lauder stopped at Poictiers and writes, "I was beginning to make many acquaintances at Poictiers, to go in and drink with them, as,"—then follow several names, then a note by the editor that twenty-seven lines have been erased in the MS. It continues: "I was beginning to fall very idle." Later on: "I took up to drink with me M. de la [32]Porte, de Gruché, de Gey, de Gaule, Baranton's brother, etc."; [twenty-two lines erased] "on my wakening in the morning I found my head sore with the wine I had drunk." Even if one was wrong-headed enough to agree with what the minister at Fountainhall would feel obliged to remark about such occurrences, nothing could counterbalance the advantage to a Scot of learning that the Scottish opinion of Scots was not universally accepted. Lauder is surprised, genuinely humiliated, to find his countrymen despised abroad for the iconoclasm that accompanied their "conversion."

Lauder wrote a diary: the Duc de Rohan a "letter" to his mother, summarising the valuable information acquired in a virtuous perambulation through Italy, Hungary, Bohemia, Germany, the Low Countries, England, including a flying visit to Scotland; an harangue of flat mediocrity, imitative in character, thoughtful only in so far as, and in the way, he had been taught to be thoughtful. But, read between the lines, it is most interesting; better representing the Average Tourist in his nominal every-day state of mind than any other book. He embodies the sayings and doings of hundreds of others whose only memorials are on tombstones or in genealogies; he endures the inns in silence; never ate nor drank nor saw a coin or a poor man, for aught he says; passed the country in haste, ignoring the scenery except where "classical"[33] authors had praised it, considered the Alps a nuisance, and democratic governments a degraded, albeit successful, eccentricity; and hastened past the Lago di Garda, in spite of the new fortress in building there, to Brescia, the latter being "better worth seeing." It was just 1600 when he travelled, and the ideas of the year are reflected in his opening lines with an exactitude possible only to one who has the mind of his contemporaries and none of his own. "Peace having been made, I saw I could not be any use in France." So he employed his idleness in attempting to learn something, in noting the differences in countries and peoples. Yet he would not be the Average Tourist made perfect that he is if there was not some idea of the future hovering in him—he is the only traveller, except Sir Henry Blount, the philosopher, who notes, or even seems to note, that the chief factor of differences between human being and human being is geography.

Yet underneath all the special characteristics which distinguish everyone of these tourists from every other, there remains one that all share with each other and with us, that expressed with the crude controversial Elizabethan vigour in some lines which Thomas Nashe wrote towards the close of the sixteenth century—"'Countryman, tell me what is the occasion of thy straying so [34]far ... to visit this strange nation?' ... 'That which was the Israelites' curse we ... count our chief blessedness: he is nobody that hath not travelled'"—the sense of the inexhaustible pleasure of travel. Had it been otherwise they would not have cared to write down their experiences; nor we to read them. And if at times it is hard to find a reflection of their pleasure in what they have written, it is certainly there, if only between the lines, manifesting how this continual variety of human beings is brought into touch, even if unconsciously, with the infinite change and range of the ideas and efforts of millions of persons over millions upon millions of acres, each person and each acre with its own history, life, fate, and influence. If, too, in the course of summarising what they experienced, the more trivial details seem to occupy a larger proportion of the space than is their due, it may be suggested that that is the proportion in which they appear in the tourists' reminiscences.

The permanent undercurrent I have tried to suggest where circumstances bring it to the surface in some one of its more definite forms.

Now resteth in my memory but this point, which indeed is the chief to you of all others; which is, the choice of what men you are to direct yourself to; for it is certain no vessel can leave a worse taste in the liquor it contains, than a wrong teacher infects an unskilful hearer with that which will hardly ever out.

Sir Philip Sidney's advice to his brother

(about 1578).

From what has been said already, two conclusions may be drawn: first, that the Average Tourist was given much advice; secondly, that he did not take it. Let us too, then, see the theory for one chapter only; and, in all chapters after, the practice.

It must have amused many a youngster to hear the down-trodden old gentleman, whom his father had hired, setting forth how the said youngster must behave in wicked Italy if he was to grow up in favour with God and man; all the more so if the old gentleman, whose name, perhaps, was the local equivalent for John Smith, published his advice in Latin under a Latin pseudonym, say, Gruberus or Plotius. Gruberus and Plotius suggest themselves because they are the very guidiest of guide-book writers. They, like all the orthodox of their kind, begin by a solemn argument for and against travelling. They bring up to support [36]them a most miscellaneous host: the Prophets, the Apostles, Daedalus, Ulysses, the Queen of Sheba, Theseus, Anacharsis, the "Church of Christ," Pythagoras, Plato, Abraham, Aristotle, Apollonius of Tyana, Euclid, Zamolxis, Lycurgus, Naomi, Cicero, Galen, Dioscorides, him who travelled from farthest Spain to see Livy ("and immediately," as some one most unkindly says, "immediately he saw him, went away"); Solon also and St. Paul, and Mithridates, the Roman Decemviri, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Pausanias, Cluverius, Moses, Orpheus, Draco, Minos, Rhadamanthus, Æsculapius, Hippocrates, Avicenna, the physicians of Egypt and the gods of Greece. But there is not a word about Jonah; perhaps his luck and experiences were considered abnormal; or perhaps because, as Howell says, "he travelled much, but saw little."

Then there are those who have to be refuted or explained away: Socrates, Seneca, the Lacedaemonians, Athenians, Chinese, Muscovites, Psophidius, Elianus, and Pompeius Laetus. Cain, also, the first traveller, creates a prejudice. Likewise, the argument from experience has to be met. Some return from travel, they say, using phrases without meaning, pale, lean, scabby and worm-eaten, burdens on their consciences, astounding garments on their backs, with the manners of an actor and superciliously stupid. Yet is this not due to the thing itself, but to the abuse thereof; [37]peradventure he shall be corrupted more quickly at home than abroad, and there is less to be feared from universities and strange lands than from the indulgent mother. Moreover "non nobiliora quam mobiliora"; the heavens rejoice in motion, and transplantation yieldeth new life to plants. And shall the little sparrow travel as he pleases and man, lord of the animals, be confined to a farm or a hamlet?

Reason, erudition and emotion having thus conquered, instruction begins. The forethought necessary is as great as if he were choosing a wife. For tutors and horses, it seems, the most that can be expected from them is that they shall not imperil his soul and body respectively. First among requisites is a book of prayers and hymns effective for salvation without being so pugnacious, doctrinally, as to cause suspicion. Next, a note-book, a watch, or a pocket sun-dial; if a watch, not a striker, for that warns the wicked you have cash; a broad-brimmed hat, gaiters, boots, breeches (as if his friends would let him start without any!), gloves, shoes, shirts, handkerchiefs, "which come in useful when you perspire"; and if he cannot take many shirts, let those he takes be washed, he will find it more comfortable. Also, a linen overall, to put over his clothes when he gets into bed, in case the bed is dirty. Let him get to know something of medicine and, "like Achilles," learn to cook before he leaves home. Travel not at night, and, [38]in daytime, be guarded by the official guards which German and Belgian towns provide; or travel in company.

Now, the aim of travelling is the acquisition of knowledge; stay, therefore, in the more famous places rather than keep on the move. Enquire, concerning the district, its names, past and present; its language; its situation; measurements; number of towns, or villages; its climate, fertility; whether maritime or not, and possessing forests, mountains, barren or wooded; wild beasts, profitable mines; animal or vegetable life peculiar to itself; navigable or fish-yielding rivers; medicinal baths; efficient fortresses. And concerning towns: the founder, "sights," free or otherwise; what the town has undergone, famines, plagues, floods, fires, sieges, revolutions, sackings; whether it has been the scene of councils, conferences, synods, assemblies, gatherings, or tournaments.

It should be mentioned that in this last paragraph I am paraphrasing Gruberus only, and presume he is confining himself to what the young tourist should discover before breakfast; otherwise he is but a superficial instructor compared to Plotius. The latter draws up a series of questions, which include enquiries about weights and measures; about the clergy, how many and what salaries; religion, is it "reformed"? if so, what has happened to monks and nuns; how often Communion is administered; and whether strangers [39]are received thereat; arrangements for burial. This last question would seem more in place at the end, but it is only number thirty-six, and there are one hundred and seventeen questions altogether. Then, is there a University? and, if so, may the rector whack the students? and concerning the professors, what they teach and what they are paid. As for local government, the enquiries exhaust possibilities. Also, how many houses; and what about night-watchmen; legal procedure; "ancient lights," the right to use water, executors' duties, grounds for divorce, dress, military training? Furthermore: are the roads clean, and can children marry without their parents' consent? concerning methods of cookery, and antiquity of the town; whether the position of an officer of justice is a respected one or not; concerning notaries public; and whether the water used in cooking comes from river, fountain, well, or rain; how many varieties of grain are used in bread-making; and what means have they for dealing with fires; their sanitary arrangements and public holidays, with the reasons for the latter; care of paupers, orphans, and lepers; what punishments for what crimes.

It must not be imagined that Gruberus and Plotius thought of all this by themselves: they copied others, being but two among many. Where the copying reached its most uncritical extreme was in the origins ascribed to towns: Paris, the [40]guide-books say, was founded by a Gaul of that name who lived two hundred years before his namesake of Troy; Haarlem is also named after its founder "Herr (i.e., Mr.) Lem"; Toulouse dated from the time of the prophetess Deborah; and so on.

But to consider the foregoing instructions, and even these three "facts," on their humorous side only, is to miss much of their interest. Two, for instance, of these etymologies are but examples of what is not only continually coming into notice in books of this date, but is especially noticeable in guide-books and tourists' notes, in which latter the habit of mind of the time is more exactly mirrored in its daily attitude than in any other class of books. They exemplify the two sources of knowledge of antiquity, the two standards of comparison, then available: classical and biblical; of more nearly equal authority than they were before or have been since; and they were the only ones. So with the objects of enquiry: they are implied by that lack of reference books from which not only the tourist, but governments also, suffered; it is clear, for example, that in 1592 much elementary information was not at hand, even in manuscript, in England.[15] The Tsar, moreover, about this time addressed a letter to the "Governor of the High Signiory of Venice," his advisers thinking that Venice was governed by a nominee of the Pope; and Rivadeneyra, who was very well-informed[41] about affairs English, says in his "Cisma de Inglaterra," written thirty years after the reform of the English currency under Elizabeth: "The gold and silver currency is not so pure nor so fine as it was before heresy entered into the kingdom, for in the time of Henry VIII and his children Edward and Elizabeth, it has been falsified and alloyed with other metals, and so the money is worth much less than it used to be." Camden again, who wrote his Annals of Elizabeth's Reign early in the next century to correct misconceptions to which foreign scholars were liable, thought it necessary, when he mentioned Dublin, to explain that it was the chief city of Ireland; and very reasonably, too, considering that one of Henry VIII's officials in Ireland wrote home: "Because the country called Leinster and the situation thereof is unknown to the King and his Council, it is to be understood that Leinster is the fifth part of Ireland."[16] And there was a certain gentleman at the court of King James I, supposed to be an authority on things Continental, who answered, when asked for information about Venice, that he could not give much because he had ridden post through it—and it was not till the questioner got there that he became aware that Venice was surrounded by water; just as the secretary of a Spanish duke in England writes that his master took ship from "Calais, because, England being an island, it cannot be approached by land."

It may perhaps seem that the absence of knowledge which is ordinary now, indicated by the above illustrations, was extraordinary rather than ordinary even then. But the fact was that, besides the available books being practically always too much behind the times for any but antiquaries' purposes, the writers themselves had so little information at hand that it was only here and there their writings were anything but hopelessly superficial, even when obtained; and to obtain them was no easy matter. There were at least three men who published practical handbooks in English for Continental travelling later than Andrew Boorde and earlier than Howell; yet they, and Howell also, each claim that theirs is the first book of its kind in English. Whether the statement is made in good faith, or for business purposes, it proves equally well that even if a book was written, it was not easy to find.

Or again, take a book which was so often republished as to be easy to obtain, the "Viaggio da Venetia al Santo Sepolcro," for instance, the authorship of the later editions of which is ascribed to one Father Noë, a Franciscan. The first edition seems to be that of 1500, and it continued to be reprinted down to 1781; at least thirty-four editions came out before 1640, when the period under consideration ends. It was not, however, an Italian book originally, having been translated from a German source which was in existence as early [43]as 1465, if not earlier.[17] Since, therefore, its information was never thoroughly revised, at any rate, not before 1640, sixteenth-century and seventeenth-century pilgrims went on buying mid-fifteenth-century information. They were recommended, for instance, to go by the pilgrim galley, which ceased to run about 1586; and also to take part in a festival held yearly on the banks of the Jordan at Epiphany, which must have been abandoned far earlier even than that.

Still, books about what there was to notice in given places did exist just as there were treatises of the Gruberus and Plotius kind unfolding what should be noticed in general, and why. Best known of the earlier kind was Münster's gigantic "Cosmography," which Montaigne regretted he had not brought with him; and by the middle of the seventeenth century several other first-rate geographers, besides minor men, had compiled books of the kind. But the bearing of such books on our subject is only in so far as they reflect the thoughts, and ministered to the needs, of the tourist; and they may therefore be best considered in the works of those who wrote "Itineraries," which not only recorded journeys but were meant to serve as examples of how a journey might be made the most of. Such a book was Hentzner's, a sort of link between Gruberus and Fynes Moryson. Hentzner was a Silesian who acted as guide and tutor to a young nobleman [44]from 1596 to 1600. They began, and ended, their journey at Breslau, and toured through Germany, France, Switzerland, Italy, and England; the "Itineraria" being based on notes made by the way. His account of England does him rather more than justice, for there is some first-hand experience there, which is just what is lacking in the rest of his book. Practically everything he says is second-hand, and the fact of his being at a place is merely a peg to hang quotations on. When he is not quoting from books he seems to be quoting from people; and half of what we expect from a guide-book is absent: means of conveyance, for instance. This is an omission, however, which can be explained: he was only concerned with the most respectable form of travelling, and that meant, on horseback. And the rest of his omissions, taken all together, throw into relief the academic character of the book, due, not to himself individually so much as to the period. His preface cannot, naturally, differ much from Plotius, nor add much, except in recommending Psalms 91, 126, 127, and 139 as suitable for use by those about to travel, forgetting, it would seem, the one beginning, "When Israel went forth out of Egypt," which Pantagruel had sung by his crew before they set out to find the "Holy Bottle"; and being a Protestant he cannot recommend the invocation of St. Joseph and St. Anthony of Padua, the patron [45]saints of travellers; all he can do is to pray at the beginning for good angels to guard his footsteps, and, at the end, to acknowledge assistance from one, although it does not appear that he ever went to the length of Uhland's traveller:—

and paid a fare for the good angel. On the way, having reached, say Rome, he does not, in Baedeker's merciful fashion, tell you the hotels first, in order of merit, but begins straightway: "Rome. Mistress and Queen of Cities, in times past the head of well-nigh all the world, which she had subjected to her rule by virtue of the sublime deeds of the most stout-hearted of men. Concerning the first founders thereof there are as many opinions, and as different, as there are writers. Some there are who think that Evander, in his flight from Arcadia," etc. Yet no one could write over six hundred pages about a four years' tour in sixteenth-century Europe without being valuable at times; partly in relation to ideas, partly to experiences into which those ideas led him and his pupils.

It was less than twenty years after Hentzner that another German published a record of travel which was also meant as a guide. But time had worked wonders; it was not only a personal difference[46] between the former and Zinzerling that accounts for the difference in their books; it was the increase in the number of tourists. The latter sketches out a plan by means of which all France can be seen at the most convenient times and most thoroughly without waste of time, with excursions to England, the Low Countries, and Spain. Routes are his first consideration; other hints abound. At St. Nicholas is a host who is a terror to strangers; and remember that at Saint-Savin, thirty leagues from Bourges, is the shanty of "Philemon and Baucis" where you can live for next to nothing; and that outside the gate at Poictiers is a chemist who speaks German, and so on. Frequently, indeed, he notes where you may find your German understood; and also where you should learn, and where avoid learning, French.

Advice of this last-mentioned kind calls to mind a third class of guide-books, intended to assist those who, without them, would realise how vain is the help of man when he can't understand what you say. The need for such became more and more evident as time went on and Latin became less and less the living and international language it had been but recently. The use of vernaculars was everywhere coming to the front as nationalities developed further, and in many districts where it had been best known its disuse in Church hastened its disuse outside.

The extent to which Latin was current about 1600 varied in almost every country. Poland and Ireland came first, Germany second, where many of all classes spoke it fluently, and less corruptly than in Poland. Yet an Englishman[18] passing through Germany in 1655 found but one innkeeper who could speak it. The date suggests that the Thirty Years' War was responsible for the change. It is certainly true that France in the previous half century was far behind Germany in the matter of speaking Latin, as a result of the civil wars there. Possibly the characters of its rulers had something to do with this too, just as in England, where Latin was ordinarily spoken by the upper classes, according to Moryson, with ease and correctness, the accomplishments of Queen Elizabeth as a linguist had doubtless set a fashion. This much, at least, is certain: that in 1597 when an ambassador from Poland was unexpectedly insolent in his oration, the Queen dumbfounded him by replying on the spot with as excellent Latinity as spirit, whereas at Paris once, when a Latin oration was expected from another ambassador, not only could not the King reply, but not even any one at court. With Montaigne the case was certainly different, but then his father had had him taught Latin before French, and consequently, on his travels, so soon as he reached a stopping-place, he introduced himself to the local priest, and though neither [48]knew the other's native language, they passed their evening conversing without difficulty.

Very many were the interesting interviews that many a tourist had which he owed to a knowledge of Latin; the extent to which knowledge was acquired orally having led to its being an ordinary incident in the life of the tourist to pay a call on the learned man of the district; a duty with the Average Tourist, a pleasure for the others. And Latin was the invariable medium, part of the respectability of the occasion. At least, not quite invariable: when the historian De Thou visited the great Sigonius, they talked Italian, because the latter, in spite of a lifetime spent in becoming the chief authority on Roman Italy, spoke Latin with difficulty.

It seems curious that Latin should have been less generally understood south, than north, of the Alps, but such was the fact. Italy was, however, ahead of Spain, where even an acquaintance with Latin was rare. In the first quarter of the sixteenth century Navagero found Alcalá the only university where lectures were delivered in Latin, and, according to the best of the guide-book writers on Spain, Zeiler, the doctorate at Salamanca could be obtained, early in the seventeenth century, without any knowledge of Latin at all; while it has been shown by M. Cirot, the biographer of Mariana, that the latter's great history of Spain, published in Latin at this time, [49]and as successful as a book of the kind ever is in its own day, was unsaleable until translated into Spanish.

Among those, too, who did know Latin there was the barrier of differing pronunciation. Lauder of Fountainhall was very much at sea to begin with, in spite of his Scotch pronunciation being much nearer to the French than an Englishman's would have been, and there is an anecdote in Vicente Espinel's "Marcos de Obregon" which is to the point here. The latter is a novel, it is true, but the tradition that it is semi-autobiographical is borne out by many of its tales reading as if they were actual experiences, of which the following is one. One day, the hero, a Spaniard, found himself in a boat on the river Po, with a German, an Italian, and a Frenchman, and to pass the time they tried to talk Latin so that all could understand each one; but they soon abandoned the plan, as the pronunciations varied too greatly.

Nevertheless, the passing of Latin out of European conversation is to be attributed rather to the growth of Italian, and later of French, as international tongues. Gaspar Ens, who wrote a series of guides to nearly every part of Europe, says in his preface to the volume on France, "At this day their language is so much used in almost every part of the world that whosoever is unskilled therein is deemed a yokel." This was in [50]1609, at which date, or soon after, it was as true as a general statement can be expected to be; just as much so as the assertion in the preface to an English book in 1578: "Once every one knew Latin ... now the Italian is as widely spread."[19]

It was only in the north that French came to rival Italian during this period, for the "lingua franca," also known as "franco piccolo," the hybrid tongue in which commerce was conducted along the shores of the Mediterranean, was so largely Italian that to the average Britisher, from whom Hakluyt drew his narratives, the two were indistinguishable; but an Italian would notice, as Della Valle did, that no form of a verb but the infinitive was used. If any one was met who knew more than two languages, he would oftenest be a Jew, who usually knew Spanish and Portuguese; the latter because the tribe of Judah, from which their deliverer was to come, was supposed to be domiciled in Portugal.

Another hybrid language, as well established in its own area as the "lingua franca," was Scot-French, so constantly in use as to have an existence as a literary dialect as well as in French burlesque. These mixed languages have no place in the ordinary book-guide to languages, but were left to personal tuition; yet in the lists of the most common phrases which Andrew Boorde appends to each of his descriptions of countries may be noted a curious instance from this borderland [51]of philology. In both the Italian and the Spanish lists he renders "How do you fare?" by "Quo modo stat cum vostro corps?"