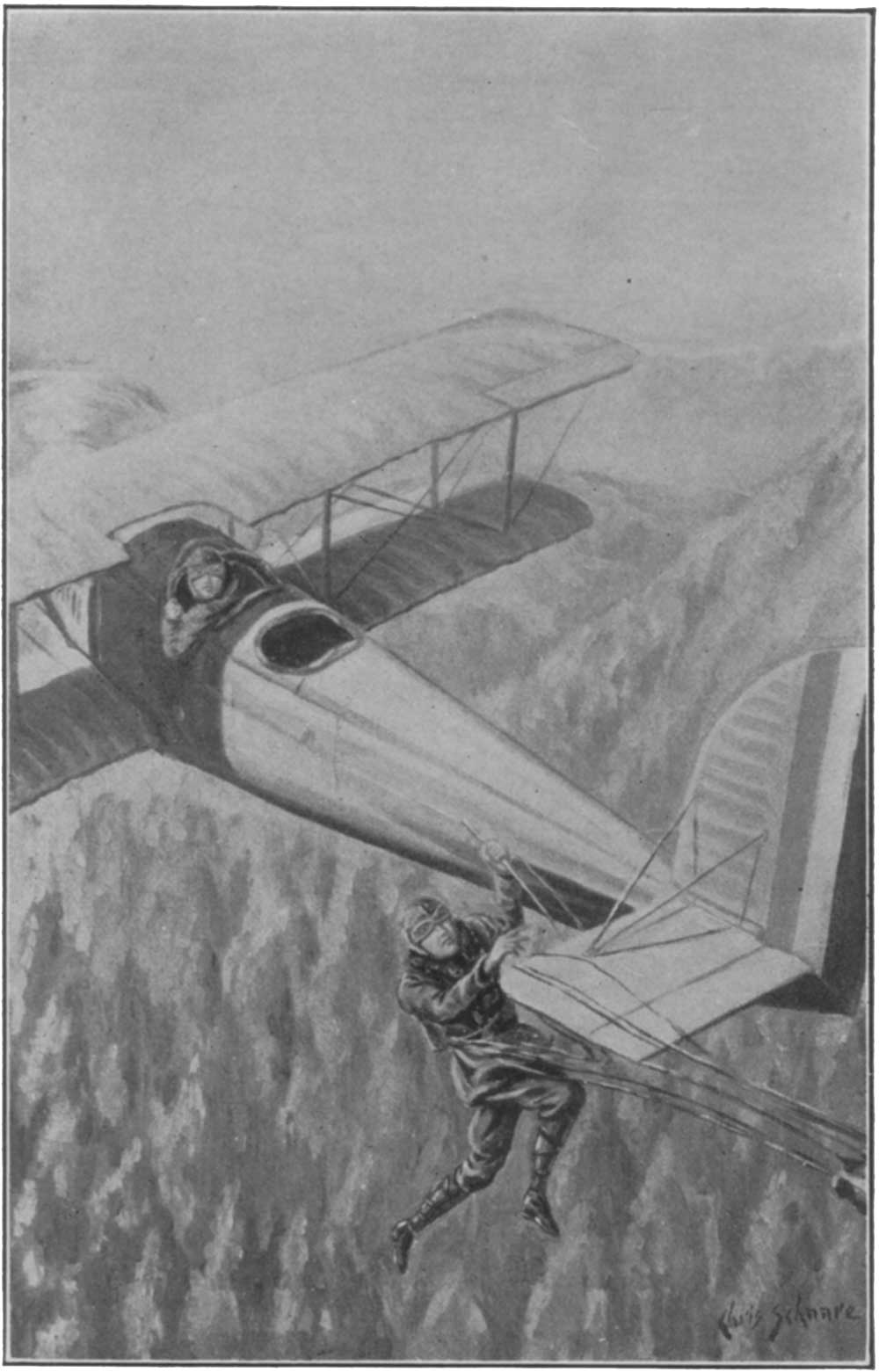

Bill worked his way backward toward the tail group.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Bill Bruce on Forest Patrol

Author: Henry Harley Arnold

Release Date: February 28, 2015 [eBook #48377]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BILL BRUCE ON FOREST PATROL***

Bill worked his way backward toward the tail group.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | A VACATION IN THE WOODS |

| II | THE FORESTRY SERVICE |

| III | WOOD LORE |

| IV | DRAFTED TO FIGHT A FOREST FIRE |

| V | A FOREST FIRE |

| VI | BACK TO ARMY DUTIES |

| VII | WORKING WITH THE ARTILLERY |

| VIII | NARROW ESCAPES |

| IX | AN UNEXPECTED DUTY |

| X | CLOUDS ON THE SISKIYOUS |

| XI | INTO THE SMOKE PALL |

| XII | A FOREST PATROL BASE |

| XIII | THE AERIAL FIRE PATROL |

| XIV | DOWN IN THE TIMBER |

| XV | ON FOOT MILES FROM ANYWHERE |

| XVI | A LOOKOUT STATION IN THE MOUNTAINS |

| XVII | BACK AT EUGENE |

| XVIII | THE WEATHER CHANGES |

| XIX | FISHES LARGE AND SMALL |

| XX | MORE ABOUT FISH |

| XXI | THE EUGENE AIRDROME |

| XXII | TRAPPED IN MIDAIR |

| XXIII | A NEW OUTBREAK OF FIRES |

| XXIV | HUNTING A FIREBUG |

| XXV | THE END OF THE FIRE SEASON |

“Wake up, Bill, there’s a big fish on your line.”

“I should worry,” replied Bill as he lay on his back on the bank of the McKenzie River. “Let him do the worrying. I am having a marvelous time just lying here thinking how wonderful it is to be here in the Oregon woods. Perhaps in a day or two I will get sufficiently accustomed to the big outdoors, the gigantic trees and the wildlife to get enthusiastic over a fish. In the meantime, let him bite.”

Bill Bruce and Bob Finch were officers in the United States Army Air Service. They had been boyhood friends in Flower City, Long Island. At the outbreak of the World War they had enlisted as Flying Cadets and had been sent to the Ground School at the University of California, at Berkeley. They had both finished the ground work and then completed their flying training at the aviation field near Lake Charles, Louisiana.

A West Indian hurricane broke the monotony and routine of their training at the flying school and Bill was sent as a test pilot at an airplane factory. Bob had been sent to the aviation field at Mineola. Bill’s new duties required that he test out the latest type airplanes produced for the squadrons in France. It was here that he ran afoul of the dastardly work of a German sympathizer.

While Bill had been at Berkeley, another cadet by the name of Andre had become rabidly jealous of Bill. Andre had tried to discredit Bill and make out that Bill had cheated in an examination. Andre was fired. While at the airplane factory Bill had several narrow escapes, when airplanes which he was testing were found to be maliciously damaged. Andre was the culprit. He was caught, convicted, and was being taken to the penitentiary, but escaped.

Later Bill was sent to France, presumably with plans of the latest type airplane being produced, the Le Pere. While on board the ship, as Adjutant, he made frequent inspections to insure that the regulations concerning lights on deck were being carried out. On several instances he escaped being assaulted on the dark decks by a very narrow margin. His cabin was searched and it was quite evident that someone was endeavoring to secure the plans.

Finally, as the ship was nearing the coast of Ireland, Bill saw someone flashing lights from the deck. He tried to catch the miscreant, but was not successful on account of the darkness. The next day the ship was torpedoed. As the small boats were floating around, the sub came to the surface and took someone from one of the boats aboard. It was Andre. The Germans then tried to find Bill Bruce, but were prevented by the timely arrival of the U. S. destroyers.

Bill served at the front in the 94th Pursuit Squadron with Freddie Rickenbacker. He shot down his first plane, however, before joining up with the squadron. He was shot down between the lines in No-Man’s-Land and had several thrilling escapes during combats in the air, but came out of the war with a wound, several decorations and the title of “Ace.”

Following the war, Bill served on the United States-Mexican border with the Ninth Squadron. The work of the squadron required that they make frequent aerial patrols to prevent the smuggling of liquor, dope and aliens into the United States. Here again they ran afoul of Andre, who was masquerading under the name of Andrajo. Andre had organized a large gang of cut-throats for the one and only purpose of smuggling.

The squadron helped the border officials materially in uncovering this work. They were assigned the part of the border extending from San Diego, California, to Yuma, Arizona. Captain Lowell Smith was commanding the squadron and Bill Bruce was his senior flight commander. The pilots had been able to catch an airplane in the act of transporting dope, had broken up Andre’s attempt to make a forcible entry into the United States with four hundred Chinese, and thus had broken up the gang of renegades.

In the Fall, Bill had entered the trans-continental airplane race from San Francisco to New York and return. Bill met Andre again before and during the race. Andre sneaked across the line at El Centro and removed all the safety wires and cotter keys from the controls of Bill’s plane. For a while it looked as if Bill would not be able to get to San Francisco in time to participate, but he arrived the evening before the start.

Once in the race, Bill thought that he was entirely out of Andre’s reach, but on the return trip Bill’s plane was completely burned at Buffalo. Andre had again shown his hand. Bill secured authority to fly another plane, and after many difficulties and much hard flying won the race in spite of the fact that he landed at the finish with a dead engine. It had been a most spectacular and uncertain race from start to finish. Bill had won it by inches.

After the race the Ninth Squadron was relieved from border duty and sent to San Francisco for duty. Here they established a new airdrome along the shores of the bay almost within hailing distance of the Golden Gate. During the Winter and Spring, the pilots had been kept very busy with routine flying. It was now June and Bill Bruce and Bob Finch had taken a few days’ leave to get away from military routine. They had driven to Oregon by automobile and were spending their time fishing along the McKenzie River.

“A fine young fisherman you are,” said Bob as he ran over and grabbed Bill’s rod. “Did you come up here to fish or to day-dream?”

“Both,” answered Bill as he watched Bob struggle with the fish.

It was very evident that it was an unusually large fish, for it was putting up a hard fight. The rod bent almost double when the fish made a run for freedom. Bob was forced to let out more line to keep the fish from breaking the leader or snapping the rod. Bill was entirely satisfied to watch Bob’s endeavor to land the fish.

The stream was in general clear of snags and rocks, but there was one large tree trunk with several branches in the water toward which the fish always headed. To make matters more complicated, the banks of the river were lined with small bushes.

“I should say that it was a large fish,” said Bill after Bob had vainly tried for several minutes to bring it in. “It will get away from you yet.”

“Why don’t you come here and take your own rod then?” asked Bob.

“You are getting along very well. I wouldn’t think of depriving you of the pleasure of landing the first trout,” said Bill as he stood up and walked over to the place where Bob was working with the rod.

“Get the net,” called Bob. “I am getting it in close enough for you to catch him.”

The bank had a drop of about five feet. Bill took the net and stood looking for a place to get down to the water’s edge without getting his feet wet. He walked a short distance upstream and then slowly worked his way down to the water.

“You poor boob,” said Bob. “How can you get the fish way over there? There are a dozen bushes between us.”

“Swing your rod around this way,” called Bill.

“Come closer, I am not fishing with a telegraph pole.”

“Give me time,” said Bill. “This bank is slippery and I am liable to get wet.”

“Hurry up,” answered Bob. “I can’t keep working this fish forever.”

Once more the fish gave a violent pull on the line and Bob had to give it more line. Then he had the job of gradually reeling in the line as fast as he could while the fish darted around in large circles in the water. Once it made straight for the old tree trunk and both young aviators were sure that the line would get afoul of one of the branches, but by careful manipulation Bob managed to get the fish back into open water.

Bill meanwhile worked his way along the bank toward Bob. The point where the line entered the water came closer and closer to the shore. Bill reached out with his net, but could not quite stretch far enough.

“Bring it in a bit,” called Bill.

“Your rod is almost bent double now,” replied Bob. “Do you want me to break it?”

“Well, you’re the fisherman of this crowd,” said Bill. “It was you who suggested a vacation in the Oregon woods. I admit that I don’t know how to use this net. What do you do with it, immerse it gently in the water under the fish or make a wild swoop with it and scoop up the fish?”

“How do I know?” replied Bob. “I never saw one before.”

“I would rather have a shotgun and then I would be sure of getting the fish,” said Bill. “Don’t slow up on bringing him in while you are talking, for now that you have him this far, we ought to have fried trout for lunch.”

Bill stood on a stone near the bottom of the bank. There was just room enough for one of his feet. The other was dangling over the water. He was holding on to a small bush with one hand and leaning out over the water with the net in his other. Bob gradually worked the fish in closer to the shore.

“Bring him in closer. Reel in on your line,” called Bill. “I can’t stand down here forever.”

“I am trying to,” replied Bob. “There he is; catch him.”

The fish was now in close enough to be seen. It was a large fellow and must have weighed about two or three pounds. For a while Bill could do nothing but watch it as it worked its way back and forth against the taut line.

“Well, do something,” called Bob.

Bill then gave a violent swing with his net. As it hit the water with a splash, Bill lost his balance and fell prone into the water. For a while, line, net, fish and Bill were all tangled up in one small space. Bob did not know what to do. If he slackened up on the line, the fish would escape. If he didn’t, Bill would probably break the line.

“Get out of there, you will make me lose the fish,” yelled Bob.

The water was not deep and Bill came up after the splash in a kneeling position. He blew the water out of his mouth and nose and looked around. It was at that moment that Bob had called to him.

“You don’t think that I am here because I am enjoying it, do you?” he replied.

Then it was that Bob realized that the tension on his line had ceased. The fish was gone. Evidently the splashing around in the water had been enough to slacken the line and the fish had taken advantage of the opportunity to make its getaway.

“Well, the fish is gone,” said Bob. “You are a fine help. Come on out of the water.”

“What’s going on here?” called a deep voice from the bank.

Bob looked around to see who had asked the question. He saw a tall, lithe, dark-complexioned man in a grayish-green uniform. He wore a broad-brimmed felt hat, with the crown coming to a peak, and had a badge on his shirt.

“We’re fishing, and Bill fell into the water,” said Bob.

In the meantime Bill scrambled up the bank.

“I am the District Forester. My name’s Cecil. Have you a fishing license? Have you a campfire permit?”

“What I should have had was a bathing permit,” remarked Bill as he started to wring the water out of his clothes.

“I am Lieutenant Finch, and this is Lieutenant Bruce. We both are members of the Army Air Service,” said Bob when Bill had ceased speaking. “We have fishing licenses, but no campfire permits. We just arrived here this morning and haven’t had occasion to light a fire so far.”

“Babes in the woods,” remarked Cecil. “It is obvious that this is your first visit in a National Forest. No one is permitted to light a fire for any purpose in a National Forest during the forest fire season without a campfire permit. It is fortunate that I ran into you when I did, otherwise you might have been picked up by one of my rangers and then it would have cost you something as a fine. First I will fix up the permits, and then I will tell you something about these forests.”

Cecil then made out campfire permits for each of the two young aviators. He then gave them a large size “Help prevent fires” slogan to put on the windshield of their car.

“Let’s sit down,” said Cecil.

“You are both officials of the United States Government and, as such, should know something about our forestry service and what it does,” he continued after they had seated themselves on a log overlooking the river. “As you look at these giant trees around you, they probably don’t mean much to you. That Douglas fir over there is close to two hundred years old. Some of those pines close by are just as old. You can see that the lowest branches are over a hundred feet above the ground. The tops of those trees are over three hundred feet above us. An entire forest of those trees can be destroyed in a few hours through the carelessness of a man who is enjoying a vacation in the woods.”

“I never knew that trees grew so large,” said Bill. “I have seen the giant Redwood trees in California, but I thought that they were freaks of nature—that they were abnormal in timber life.”

“These trees are not as large in diameter as the California Redwoods, but there are a great many more of them,” replied Cecil. “We have mile after mile of trees as large and larger than these in Oregon and Washington. In order to protect these trees, the government has set aside certain forest preserves which are called National Forests. There are 152 National Forests in the United States. Each of these National Forests has a supervisor in charge. He has under him wardens, rangers and lookouts. These men all work to detect and suppress fires.”

“That is a large organization,” said Bill. “Why are so many men needed?”

“The forests in the United States cover a large area,” replied Cecil. “About twenty-nine per cent of the land area of the United States is covered with timber. This timber is valued at six billion dollars. Think of that. The Forestry Service has as its duty the protection of that government property.”

“I never knew that there was so much timber in this country,” said Bob. “We saw quite a lot as we drove up here, but six billion dollars’ worth is way beyond my comprehension.”

“There is a vast amount of timber here in the Northwest,” said Cecil. “In fact about one fourth of all the timber in the United States is located in Oregon and Washington. In spite of the fact that this timber is worth money, most of the fires in the forests are caused by the carelessness of man.”

“You don’t mean that they deliberately set the woods on fire, do you?” asked Bill.

“They don’t mean to, but the results are the same,” replied Cecil. “A camper forgets to put out his fire, he throws away a cigarette butt without extinguishing it, or he lights a cigar or pipe and throws the match down on the ground and the spark ignites the surrounding dried leaves. Then a fire is started in the woods. That is the reason for the campfire permits. It gives us a check on the people who come into the forests. We also have a chance to warn them about the dangers of forest fires and caution them as to the means that they should adopt to eliminate any chances of fires.”

“That’s very interesting,” said Bill Bruce. “Heretofore all that these woods have meant to me was just so many trees. Now I see the whole timbered area in a different light. Can you tell us how you go about locating a fire and what you do to put it out?”

“We have established lookouts on the highest peaks,” said Cecil. “Each of these lookouts has a map. As soon as he observes a column of smoke in the forest, he takes a sight on the fire and notes its bearing. The adjacent lookout does the same thing. As a result we have an intersection of two lines which gives the location of the fire. In the case of a small one, the local warden will gather together a few men and go and put it out. In the case of a large one, the forest supervisor mobilizes as many men as he can from the surrounding country and they try and localize it. In this way it burns itself out.”

“What do you mean by a small fire and a large one?” asked Bill.

“A small one is usually caught as soon as it starts,” replied Cecil. “A large one may cover thousands of acres and take hundreds of lives. The Hinckley fire in Minnesota burned over 160,000 acres, destroyed property valued at twenty-five million dollars and took the lives of four hundred and eighteen people. That was an unusually large fire. The Idaho fire covered larger acreage, but did not take as many lives. That fire burned over two million acres and burned eighty-five people to death. Recently we have managed to get the fires under control before they get anywhere near that large.”

“What per cent of fires are caused by carelessness?” asked Bob.

“About eighty-five per cent of the 28,000 forest fires occurring each year are due to human carelessness,” explained Cecil. “Each year we hope that the number will be smaller, but the automobiles are bringing more campers into the woods all the time. We are trying to educate our visitors up to the point where they will consider the trees their property as citizens of the United States and will guard against their destruction just as if they were privately owned. You probably have noticed the signs posted up everywhere cautioning people to use every care to prevent fires.”

“Can you always extinguish a fire with man power?” asked Bill.

“It is sometimes very hard in the case of some of the larger fires,” replied Cecil. “At times when we are about to throw up our hands in despair, a providential rain will save the day. Then, on the other hand, we may have a bad thunder storm and find as many as twenty or thirty new fires burning where trees have been struck by lightning.”

Cecil took out a pipe and lighted it. After he had the tobacco burning, Bill noticed that before throwing the match away, he broke it into two pieces.

“Why did you break that match?” asked Bill. “I noticed that it was no longer burning, and yet you seemed to be particularly careful to break it before throwing it to the ground.”

“All real woodsmen use that means of being sure that they are not dropping a spark when they think that the match is entirely extinguished. There is no doubt of the match being out by the time that you have broken it in half. That’s another thing, during certain extra dry seasons, we do not allow any smoking at all in the forests. I have bored you enough with this shop talk. May I join you in a little fishing?”

“By all means,” said Bill. “We don’t know much about it. In fact, do not know the kind of fish that we are trying to catch other than they are trout.”

“You are liable to catch steelhead, rainbow, locklaven or brook trout in the river here,” said Cecil. “What kind of flies are you using?”

“We aren’t using flies, we were using worms,” replied Bob.

“That’s no way to go trout fishing,” said Cecil. “It is not sporting. Give the fish a chance. You can get your limit with flies, so why use worms?”

“We didn’t catch any with worms,” replied Bill. “I thought that we were going to, when I fell into the river, but the big one that we had hooked broke away. We have some flies, but we did not know which to use.”

“That’s a rather hard question to decide,” remarked Cecil. “Trout are particular creatures. One can never tell at what they will strike. Some days they will strike at flies similar to those you see flying over the water. That is, if white flies are flying low over the water, use an artificial white fly. However, that rule doesn’t always hold good. I have been fishing when there were millions of live white flies all over the water and the trout would not even rise for the one on my line, but when I put a dark one on, I caught all kinds of fish.”

Cecil walked back to the trail along the river and secured his rod and line from his car. Bill and Bob watched him carefully as he put on the reel, wet his leaders in the water and then threaded his line along the rod.

“I think that I will try a dark fly,” he said, as he attached a leader to the line.

Both of the aviators were astonished when Cecil cast his line out onto the river. The line went out with his casts at gradually increasing distances until it was dropping his fly a good sixty feet from the shore. The fly landed on the water without the semblance of a splash. In fact, it alighted on the water very similar to the live flies which occasionally dropped to the water’s surface. It rested for a moment and then Cecil brought it back with a slight movement of the arm and cast to another place. Bill was too much interested to do anything but stand and watch. Bob, on the other hand, watched for a few moments and then went some distance down the river and tried to emulate Cecil’s graceful casting.

“One of the most important things to remember when fishing for trout, is to stay out of sight,” said Cecil. “Trout are wary creatures and can see you long before you can see them.”

There was a splash in the water near his fly and Cecil started to play the fish. He did it entirely different from the way that Bob had. He allowed the fish a certain amount of run, but consistently brought it closer into shore and then finally threw it onto the bank with a slight flip of his arm.

“Not so bad for a start,” said Cecil, as he unhooked the fish and held it up for Bill to see. “A three-quarter pound rainbow. A few more of these and we will have enough for lunch.”

“It looks easy enough when you do it,” remarked Bill. “I think that I will try my luck.”

“You can never learn by watching someone else,” said Cecil.

“I will go upstream a little way,” said Bill. “You will have lunch with us, won’t you?”

“Thanks very much,” replied Cecil. “I’ll meet you here at twelve o’clock. Watch out for the steelheads. You will need a net if you get a real large one on your hook.”

Bill walked a distance upstream and started to fish. He picked out a place on the bank where the bushes were low and sufficiently open for him to try casting. At first he had nothing but grief. His line became tangled in the bushes and overhanging branches from the trees. It kept him busy for quite some time disentangling his line. Once it was so badly tangled that he had to cut off part of it. Finally he managed to get it out on the water, but it landed with a splash and then only a short distance from the river bank.

The more he tried, the worse it seemed, and then he managed to make a good cast. His fly landed thirty feet or more out in the water. It had no sooner struck the water than a small trout grabbed the hook. Bill had a real thrill as he reeled the fish in. He brought it in so that he could see it swimming around in the water. Then evidently he became over-anixous, for he tried to throw it out on the bank, but instead jerked the fish loose and it was gone.

Later when he looked at his watch and saw that it was time to return, he had four small trout in his creel. He wound up his line as he walked back to the automobile. Long before he arrived he saw the smoke from a fire. Cecil was already starting lunch.

“How many did you get?” asked Cecil.

“Four,” replied Bill. “How many did you get?”

“The limit,” said Cecil. “Some of them are fair-sized fish. Some of them not so large, but just the right size for eating. Have you ever built a fire in the woods according to the approved method, which eliminates all possibility of starting a forest fire?”

“No, I never have,” replied Bill.

“You should know how,” said Cecil. “You are going to stay here in the woods for a while and it may save you a lot of trouble. I will show you now.”

“Here comes Bob,” said Bill Bruce as they walked toward the campfire. “I wonder if he had any more luck than I did.”

“How many did you get, Finch?” asked Cecil when Bob joined them.

“I managed to catch seven, but you should have seen the big fellow which broke away just as I was about to land him,” replied Bob.

“That’s the usual fisherman’s story,” said Cecil. “You already have acquired one of the prime requisites of a regular fisherman. The largest fish always gets away. Let’s see what you caught.”

“That’s a fine rainbow,” he continued, as Bob pulled the fish, one at a time, from his creel. “That one is a salmon trout. When we eat it for lunch you will see that it is different from the others in that it has salmon-colored meat. You caught a variety: rainbow, salmon, brook and locklaven. Where were you fishing?”

“I must have walked five miles down the river,” said Bob. “I followed up several streams for short distances, but I never seemed to catch more than one fish in any one place.”

“That’s natural,” said Cecil. “I imagine that you were not very careful about showing yourself over the edge of the bank. You probably were seen by the fish before or as soon as they saw your fly.”

“Mr. Cecil is going to show us how to build a safe and sane campfire,” said Bill.

“That’s a good idea,” said Bob. “If we are going to be in the woods as long as we have planned, we ought to know how to build a fire that will not start a forest fire.”

“I am glad to see that you have brought a shovel and axe with you,” remarked Cecil. “You can never tell when you will need one or both in the woods. Some Forest Supervisors require all campers to be equipped with shovels and axes before they are allowed to enter a National Forest.”

“Campfires are mighty easy things to start, but unless they are built properly, you can never tell when they are completely extinguished. The bed of pine needles, dried leaves and partially decayed wood in all forests burn very easily, and it is extremely hard to be certain that the fire has not worked its way under the surface. Many times people have left their campfires believing that they were completely extinguished when the entire area was honeycombed with sparks beneath the surface. The campers left their fire thinking that they had done their duty in regard to the rules and regulations concerning forest fires. Shortly after they had gone, the sparks would burn through to the surface and trouble would start for the fire-fighters. Such occurrences are not confined to tenderfeet alone, for some men with years of hunting and camping experience have been guilty of the same neglect.

“In building a campfire, the first thing that should be done is to dig up and clear away all the inflammable material in the vicinity of the bed of the fire. If possible, the fire should be laid on hard soil or rocks. Then a narrow trench toward the wind will furnish a draft. If you notice, I have not much wood on that fire. A lot of wood is not necessary for a hot flame. A small amount placed properly and renewed as required will give a concentrated heat. Never allow the flame to blaze higher than is needed for the cooking. When you have finished and are leaving the vicinity, if only for a couple of hours, be sure that the fire is out. You cannot put a fire out in the woods by throwing dirt on it. Go to the nearest stream and get enough water to thoroughly quench all signs of fire. The water must sink down below the surface in soil like this and extinguish any sparks which may have worked under the surface.”

“I see that you have your trout all ready for the pan,” said Bill. “I think that I will clean mine.”

“Do you know how to do it as a woodsman does?” asked Cecil.

“I never cleaned one in my life,” replied Bill.

“I’ll show you how,” said Cecil. “It is the easiest way and also takes much less time. Bring your fish down to the river.”

“There are lots of ways to clean a trout,” remarked Cecil when they reached the water’s edge. “From the forester’s point of view, there is only one right way. Take the fish in your hand with its belly up. Cut a slit across just in back of its gills. Then all that you have to do is to put your finger into the slit, grab a hold of the center of the belly with the finger and your thumb and give a slight pull toward the tail. The trout is cleaned. Three movements are all that are necessary.”

“It looks quite easy the way that you do it,” said Bill. “Now I’ll try it.”

Neither Bill nor Bob could do it anywhere as smoothly as Cecil when they first tried it, but they became more expert as they practiced. Soon they lost their awkwardness and took but a few seconds for each fish.

“Now you have the idea,” said Cecil. “It’s a good thing to remember, for it takes but a couple of seconds for each trout. However, don’t try it on fish of a coarser type, for it will not work.”

“We have a steak that we brought with us,” said Bill when they returned to the fire. “It probably will not keep much longer. We will have to cook it, too. Bob, you had better get another pan ready.”

“Why not swing the steak?” asked Cecil.

“What do you mean, ‘swing a steak’?” asked Bill. “Is that a way to fix it so that it will keep?”

“No, that’s a way to cook it,” said Cecil. “It always seems to taste better after being cooked that way. I don’t know whether it is imagination or whether the fragrance of the burning wood really does permeate into the meat. Have you a griddle? If you have, we will try it.”

“I’ll get the griddle,” said Bill.

Cecil took the griddle and suspended it by three wires so that it hung in a horizontal position. He then attached the wires to a tripod made from some saplings. By the time that he had finished, the trout had been fried and were placed along side the fire to keep warm. Cecil took the tripod and placed it over the fire. The steak was placed in the griddle and gently swung back and forth just above the tops of the flames.

“Get a stick, Bruce,” said Cecil. “You can swing this while I do something else. As soon as the bottom starts to get brown, turn the steak. That will keep the juice in the meat. It begins to look as if we are going to have a real meal. I am sorry that some of my Oregon friends did not happen along with a venison mince pie. If we had one of them, we would be sitting on the top of the world.”

“It is nothing more than mince pie made out of venison instead of regular meat,” he continued when he saw the surprised expression written on the faces of the young aviators. “These Oregon people make them during the Fall and Winter. If you ever get a chance, be sure and taste one.”

In the meantime, Cecil was busy arranging the plates, knives, forks and spoons on an improvised table on the top of an old tree trunk. Smaller logs were brought up for chairs. So it was that Bill and Bob ate their first meal in the woods. Trout, baked potatoes, bread, butter, jam, coffee and, best of all, the steak. It was as Cecil had said, “Better than when cooked in the ordinary manner.” It seemed to have absorbed some of the pungent aroma of the burning wood.

Overhead the sun was masked by a roof formed by the thickly matted trees. The smell of the timber land permeated the air, a smell which one can only find in the forest. It seemed as if they were in the wilderness, where they were the pioneers blazing the trail for others to follow. To Cecil it may have been an old story, but to Bill and Bob it was the thrill that only comes with a new and enjoyable experience.

“It seems a shame that civilized people should be responsible for the destruction of such a place as this,” said Bill after a while. “It’s all so beautiful, so entirely different from what we are accustomed to. I’ll bet that the Indians never burned the forests intentionally.”

“I am not so sure about that,” commented Cecil. “According to the best advices which we have, the Indians in some instances used to burn out the woods so that they would not be bothered by the underbrush when they were hunting. Once they started a fire, they never tried to put it out. It always burned until it reached a natural barrier and then burned itself out. However, ordinarily the Indians were very much afraid of a forest fire, as it destroyed their villages. So it seems that they liked to have the fires under certain conditions, but they wanted to apply the torch themselves.”

“There must have been some mighty bad fires in those days,” said Bob.

“The lightning has always been responsible for many bad fires as far back as we have any records,” said Cecil. “Then, again, the early pioneers were not as careful as they might have been. There is one case on record where a young fellow was returning home after calling on a young lady who lived several miles away on another clearing. It was almost dark when he started home. He was either afraid to go home in the dark or was uncertain as to the proper trail to take. In any event, he set a match to a long burr of a sugar pine. That made a very good torch and served its purpose exceptionally well. However, when the first one burned so low that it was about to scorch his fingers, he lighted another one and threw the partly consumed one down alongside the trail. He continued this all the way home, and as a result there were many small fires, about equally spaced, burning through the forest.

“That young fellow was quite proud of his achievement. He had found a new means of illuminating the trail at night, but the early settlers were not so pleased with his accomplishment. There were not many of these pioneers in the locality and they had a mighty hard time in putting out those fires. The pine needles along the trail burned fast and furious for quite a while.”

“How can you tell the age of a tree?” asked Bill.

“That can’t be done until the tree is cut down,” said Cecil. “Each year during the life of a tree a complete coating of fibre is formed around the trunk of a tree underneath the bark. These coatings take the form of rings and are called ‘Annual Rings.’ They are formed in regular sequence around the center. By counting the rings the age of the tree is determined.”

“Why go to all that trouble?” asked Bob. “If there is one ring for each year and the rings are all the same size, why not measure the diameter of the tree and divide by the distance between the rings?”

“It would be much simpler if we could do it that way, but unfortunately the distance is not the same in any two different kinds of trees, or even in the same tree,” replied Cecil. “There are many things that affect the growth of trees. For instance, if a young tree is crowded for light and room, the rings will be very close together. Then if the surrounding trees dies or are cut down and the crowded condition relieved, the young tree will grow much faster and the distance between two rings may be the same as that between seven or eight rings during the period of slow growth. Two trees growing side by side, although they may be of the same species, may have entirely differently spaced annual rings.”

“How large do trees get?” asked Bill.

“That depends upon the species,” replied Cecil. “One of the giant trees in the Sequoia National Park was undermined by a creek a short time ago and fell. That, as you know, was a Redwood. They made a cross section of that tree seventy feet above the base and it measured eleven feet in diameter. The tree was 280 feet tall and had a base diameter of twenty-one feet. The annual rings showed it to be 1,932 years old. Of course those trees are the oldest living things in the world.

“Other species do not get so large in the trunk but grow higher. You yourself remarked about that flagpole at San Francisco. That tree must have been over five hundred feet tall when it was standing here in these woods, and yet its trunk probably did not measure over fifteen feet in diameter. You can see some of the large Douglas fir and pines over there. They have not such large trunks but their tops are well up in the air. The average is well over three hundred feet. Take the Juniper, for instance; it is rare that we find one over ten feet in diameter. The foresters in Nevada made quite a news item out of one they found up in the mountains at the head of Broncho Creek. It was located at an altitude of about eight thousand feet and was a monster of its kind. For its diameter near the base was fifteen feet. It is rarely ever that we find a black walnut over fifty inches in diameter when fifty years old. An inch a year is a rapid growth for that tree.

“Well, boys, this is all very pleasant, but I must be moving along,” he continued. “It looks as if this is going to be a bad summer for fires. The woods, as you can see, are well dried out, for we have not had any rain for several weeks. If fires start, they will be mighty hard to put out. As you may judge, I am a regular bug on this forest fire business. I like the woods and am always working to protect it. Nothing would suit me better than to be able to continue with you on your fishing trip, where I could really enjoy the woods, but I have to get up to the Supervisor’s headquarters in the Cascade Forest. They had a bad fire there yesterday and it may be burning now. I may see you on the way back. Much obliged for the lunch. Don’t forget to put out your fire.”

“We are much obliged to you for starting us out right,” said Bill as Cecil walked over to his car. “I hope that you can stop over with us. Good-bye.”

The boys cleaned up after their meal and sat for a while loafing under the trees.

“Where will we spend the night?” asked Bob.

“Let’s go up the river a little farther,” said Bill.

They poured water on their fire and were packing their equipment in the car when Bill stopped working. He had caught the smell of burning wood. There was no smoke coming from his campfire, but the odor was unmistakable.

“Bob, there’s a fire somewhere around here. I can smell it.”

“There’s no fire, Bill,” said Bob. “You smell the smoke from our fire. When we put it out, it smoked terribly and the odor is all around us.”

“No, Bob, our fire has been out too long. There’s a fire somewhere near here sure as shooting. I can’t see the smoke, but I can surely smell it.”

“Well, what shall we do about it?” asked Bob.

“There’s nothing that we can do for the present,” answered Bill. “Let’s pack up and get going. We ought to pick out some place above here on the river where we can make a good camp for the night.”

They packed their equipment in their car and started up the road. The river was beautiful with the large trees on both sides. The sun was still high in the sky and here and there, where the road came out into the open, it seemed as if they had emerged from a tunnel. Everything was so much brighter. There was practically no wind and they came to long reaches where the river ran along for a considerable distance without a ripple. At other places the river ran over rapids and the splashing, bubbling water presented a decided contrast to the placid surface of the other parts of the river.

As they continued, the river became narrower, the valley in which they were traveling more confined, the sides of the mountains steeper and the vegetation thicker. They were gradually ascending into the mountains. Here and there they obtained a view through the trees of the country ahead or behind. The mountain sides were thickly covered with trees, which formed a beautiful green covering that followed the contour of the ridges and valleys. Once in a while they saw an area which had been burned over at some previous time. The snags, tall, gaunt, white skeletons of what had been magnificent trees, were scattered through the second growth timber. Nature was trying to remove all traces of the fire with the small trees, but the snags stood there as grim reminders of the forest’s former grandeur.

Here and there a pioneer had taken out a homestead and had cleared the ground in the immediate vicinity of his crude buildings. Usually some attempt had been made to cultivate part of the cleared area, but there were always a few sections still covered with the stumps of trees which had been cut. A couple of horses, several cows and some pigs roamed through the clearing as the nucleus of future herds of live stock. Bill marveled at the bravery of the men bringing their families to such a wild section of the country.

They came out on an open space where the river made a sharp curve. The road had been built on top of a steep cliff. Ahead of them was a narrow cut in the mountains through which the river flowed. Beyond the cut Bill saw what he thought to be a cloud of smoke. It seemed to be as thick and dense as a rain cloud. Bob stopped the car when Bill pointed at it.

“There must be a whopping big fire ahead of us,” said Bill. “I guess that Cecil must have arrived there right in the thick of it.”

“You must have an awful good nose, if you could smell that from where we were, five miles down the river,” said Bob. “It’s a fire all right, and looks as if it were a big one.”

“Let’s go on up and see it,” suggested Bill. “It must be an awful but fascinating thing to see.”

“All right, we are on our way,” said Bob, as he started the car again.

As they drove farther along the road the cleared spaces became less frequent. The timber closed over the road and shut out the rays of the sun almost completely. There was no doubt now as to the presence of the smell of burning wood in the atmosphere. Finally they reached a point where they were under the smoke. The sun was almost entirely obliterated from view. It was just like traveling on a cloudy day. Prior to their reaching the smoke cloud, the sun had reflected itself from the bright leaves of the trees, but now there was just a red glow which marked the position of the sun.

“We must be getting close to it now,” said Bob after a while. “The smoke is so thick that one could cut it with a knife.”

“It’s probably farther off than we think,” replied Bill. “The wind is blowing from the East and bringing the smoke toward us.

“I think that we had better stop here,” said Bob. “I don’t want to lose this car, and if we get too close the fire may burn it up before we can get it out.”

“We will probably run into the fire-fighters long before we get within the danger zone,” said Bill. “With Cecil present, they probably have certainly gathered a large bunch of men together to fight the fire.”

“We will go along a little farther and see what develops,” replied Bob.

The road wound through the trees and followed the curve of the river so that they could not see very far ahead. The visibility was further restricted by the high bushes which bordered the road and the river. They were driving slowly along a particularly narrow curving section of the road, when Bob saw another car coming around a bend just a short distance ahead. Bob slammed on his brakes. It looked as if there was going to be a collision, for the other car was approaching very rapidly. There was no room to pass, for the river was close on one side and the other side was marked by large trees.

Bill and Bob could do nothing as their car had already stopped, but the other was still moving forward. Bill at first thought of jumping out, but he saw that the other car was slowing up and decided to stick with Bob. The other car came to a stop just as the bumpers hit.

Neither Bill nor Bob had looked at the occupants of the car, as they were too busy trying to make up their minds just how hard the two cars were going to hit. Consequently they were watching the car rather than the occupants. When they did look up, they saw Cecil at the wheel.

“Wait a minute,” said Bob. “I’ll back up and you can pass.”

“All right,” said Cecil. “That was rather close. This road is not very wide and it is far from straight. I am sorry that I did not see you sooner, but I was thinking about other things.”

Bob found it rather difficult to back his car along the winding road, but he finally reached a point where there was room enough for the cars to pass. Cecil stopped his car as he came abreast.

“Where’s the fire?” asked Bill.

“It’s about four miles up the road,” replied Cecil. “It’s burning down the west slope of the next ridge.”

“We thought that we would go up and see it,” said Bill.

“I am afraid that you will do more than that,” interjected Cecil. “You will have to go up and join the fire-fighting crew.”

“We don’t know much about fighting fires,” said Bob. “But we will do what we can.”

“You will never learn any younger,” said Cecil. “Then, again, it is one of the accepted laws of the Northwest woods that anyone can be drafted to fight forest fires. We need all of the help that we can get on this one, as it has the earmarks of developing into a rip-snorter. Continue on this road for another three miles and then you will come to Sam Crouch’s clearing. Turn there and leave your car at his place. Then take your shovel and axe and follow a trail that runs almost due east from his place. Out on the trail about a mile you will see the first of the fire-fighters. Report to the forest warden, Earl Simmons. He will give you something to do and tell you how to do it. I am on my way back to Portland. It seems that several fires have broken out in other parts of this district. I have to get back on the job. I am sorry that I will not be able to go fishing with you again on this trip. Good luck to you.”

Cecil had gone almost before he had finished speaking. Bill and Bob watched the car disappear around a turn in the road and then all was quiet for a moment.

“There goes our fishing trip,” said Bob. “I had hopes of finding a nice place somewhere along here where we could fish for a couple of hours and then make camp for the night.”

“We thought that we were getting away from the constraining requirements of Army life, but we have apparently run into another service which has just as rigid demands,” announced Bill. “I guess that our fishing trip will be postponed for a while. Let’s go and see what it’s all about.”

Once more they started up the river road. The next three miles were covered very slowly as the road was not very wide and the curves were almost continuous. For a while they were afraid that they would not know Sam Crouch’s place when they came to it, but they were soon disabused of the idea, for they did not come to any clearing. They were passing through almost virgin woods.

Bob watched the speedometer with a view of checking up on the distance. It showed that they had traveled three miles, but there was not a sign of a clearing. Bob stopped the car.

“Here’s the three miles, but where’s the clearing?” he said.

“Shove along a little farther,” suggested Bill. “Perhaps your ideas of three miles from your speedometer and Cecil’s idea are not synchronized.”

“I don’t want to run right into that fire,” replied Bob. “The road may lead right through it. We are so close now that I think that I hear the flames crackling. Can you hear them?”

“I not only hear them, but also imagine that I can see them,” replied Bill. “The fire is not far off, but drive around that next bend.”

They turned the next bend and came out at the clearing. Bob drove into the cut-over area and stopped his car near the house.

“It’s the right place, all right,” said Bill. “I saw the name ‘S. Crouch’ on the mail box by the road.”

There was not a soul around the house. The chickens and live stock, the growing vegetables in the garden and the farm implements in the yard indicated that the owner could not be far away, but he was nowhere in the immediate vicinity.

“Is anyone home?” called Bill at the top of his voice.

There was no answer.

“I guess that it is up to us to find that trail leading east from here without assistance,” said Bill. “There is no doubt about our being near the fire now, is there?”

“You get the shovel and I’ll get the axe,” said Bob. “Let’s see if we can find the trail.”

“There appear to be a flock of trails leading out of here,” said Bill as they walked along. “We are going toward the fire, and I hope that we are on the right one.”

The trail wound around as it mounted the ridge. It was just wide enough for one man, so that Bill walked in front and Bob followed. The smoke became much denser, the crackling of the burning wood much stronger, and it seemed as if any moment they would walk right into the fire.

“Cecil said that it was only a mile from the Crouch house,” said Bob.

“Well, we haven’t walked a mile yet,” replied Bill as he quickened his pace.

They reached the top of the ridge and rounded a turn in the trail. Bill stopped short, for directly ahead of him was a small, rotund man standing with his back toward them.

“Is Mr. Simmons anywhere near here?” asked Bill

“You bet your neck he is,” replied the man. “I am Mr. Simmons. What can I do for you before you start work on this fire?”

“Nothing,” replied Bill. “Mr. Cecil sent us up to help you.”

“You are just in time,” said Simmons. “I am sending out a crew to try and limit the southern movement of the fire. Have either of you ever fought a forest fire before?”

“Neither one of us,” replied Bill.

“You’ll soon learn,” said Simmons. “Most tenderfeet coming up here for a vacation find it rather hard work and soon tire out, but you will be a help as long as you last.”

Simmons turned and Bill noticed three other men standing by.

“Sam,” called Simmons, “you can take these two youngsters and do that job. I will send those other men over to help Ridley.”

“This is Sam Crouch,” said Simmons as Crouch came toward them. “He will be in charge of you. All that you have to do is to follow his instructions. You had better get going, Sam.”

“Go over to that pile of tools and get another shovel,” said Sam. “One axe ought to do for both of you.”

They started out down the side of the ridge. Sam Crouch had a shovel, some gunny-sacks and an axe; Bill was carrying the same load. Bob followed along with a shovel. Bill was rather put out that he had been called a tenderfoot. He was determined that he would show them that he had the strength and endurance of any of these so-called woodsmen. He would show them when they started to work on the fire.

Crouch soon left the trail and struck directly through the woods. He walked with a long swinging stride that covered ground rapidly. Bill found that it took everything that he had to keep up. The bushes were up to their necks. The branches caught the shovels and axes, but Sam never slowed down a bit.

The footing was none too good. They were going down hill and the pine needles were slippery. When they were not traveling on the needles, they were forcing their way through dense underbrush with tangled vines and ferns which caught in their feet and tripped them. At times Bill had difficulty in keeping Sam Crouch in sight. When Bill stopped to release his feet from a vine, Sam disappeared ahead, and then Bill had to hurry to catch up. Sam never showed the slightest indications of slowing down. It was always on, on, down the mountain side.

Occasionally they would encounter a tree trunk which extended across their line of march. If it was comparatively small, Sam would jump over it. If it was too large to climb over, he would turn along the trunk and go around the end. Bill had to admit that he was getting tired.

The mountain side seemed endless. Bill was sure that Sam had lost his way and was wandering about through the forest aimlessly. He could not see the direction that they were following, for the underbrush and trees overhead limited his view to the immediate surroundings. He saw Sam stop a short distance ahead. Now they were certainly going to have a rest. When he came up to the woodsman he found out his mistake. They had reached an extra large tree trunk bordering on a steep, rocky cliff which took some maneuvering to pass.

The sun was completely hidden by the smoke, but the heat was stifling. The crackling of the burning timber sounded as if it were a few feet distant. Bill jumped backward when he heard the first falling tree. The tree dropped with a crash which resounded throughout the valley. He could not imagine what had caused the noise at first, for it had come so unexpectedly. It reminded him of the first bomb that he had heard when the Germans bombed the airdrome from which he was flying in France—no advance warning, nothing to herald its approach, just the crash and “wham” of the exploding bomb. After thinking it over, he was sure that it was a falling tree which had caused the noise. There was nothing else around which could have caused the same shattering roar. It must have been a large tree, too.

They came out into the open and Bill obtained a view of the valley below and the opposite ridge Crouch stopped to study the fire and make up his plan for fighting it. He stood awestruck, watching the terrible sight across the small valley. Bob came up and joined him. Both were tired, but the sight held them spellbound.

The fire seemed to reach from the bottom of the valley to the top of the ridge, and from one end of the mountain to the other. The exact limits were not discernible on account of the thick foliage. Smoke was boiling up with a rush over an area of about eight hundred acres. Down along the McKenzie there had not been much wind, but here around the fire a strong east wind was driving the smoke and fire before it. At times the flames shot up into the air at least a hundred feet and then died down and disappeared below the foliage. The smoke poured up incessantly.

Although they were still at least a quarter of a mile away from the near edge of the fire, the noise was deafening. Bill was watching a large tree in the midst of the fire. The fire had evidently been burning around it for some time, and it must have weathered prior fires which weakened its trunk, for it suddenly fell with a crash that sent a cloud of smoke and fire upwards with a roar. He could not tell which was the louder, the shattering crash of the tree or the roar of the flames. When the wind struck that column of smoke and fire, it scattered sparks in all directions and new fires seemed to start in parts of the forest hitherto untouched.

The fire had reached the tree tops in one section of the woods. Crouch called their attention to that particular area. It was a sight which would never be forgotten by either Bill or Bob. They were looking at one of the most terrifying of all kinds of forest fires—a crown fire. The flames seemed to be alive. They acted as if guided by some diabolical hand as they carried their destruction onward. They leaped from tree top to tree top with an incredible speed. At times their motion was almost too rapid for the eye to follow. A sheet of flames covered the tops of all the trees in that particular part of the forest so completely that the green foliage below was completely hidden.

“It’s a wonderful but appalling sight,” said Bill. “It fascinates me, but makes me shudder to see such widespread destruction. It is almost human in its method of operating. Think of the wasted force and power. Those giant trees are stripped and destroyed as if they were match sticks.”

“I don’t see what can be done to stop that,” said Bob. “It is far beyond control. It’s a monster of a fire!”

“Just stick around and you will be surprised,” said Sam. “Oak Tree Creek runs along the south end of that ridge. It has a wide meadow along portions of its banks. We will try and keep the fire from crossing that creek. I think that we can get away with it. Let’s go.”

They were off again. Bill was not so sure that he would be able to keep up with Sam. He was setting a mighty fast pace. If Sam worked as rapidly as he walked, Bill knew that it would take everything that he had to hold up his end. Once more they were tramping through the thick underbrush. The walking was hard, but it did not last very long, for they soon came out along a small creek.

The creek did not come up to Bill’s expectations. He had visioned a wide expanse of meadow land with a creek winding its way through the tall grass. What they actually found was a narrow creek which followed a natural cut through the woods. Here and there it ran through a small open space where the trees did not meet. These open spaces were the meadow land.

“I am going to start some backfires along this creek,” shouted Sam to make himself heard above the deafening roar of the fire. “We will have to watch them closely to see that they do not spread over to the other side of the creek. If the sparks blow across, put them out at once with wet gunny-sacks. I believe your name’s Bill?”

“That’s me,” said Bill.

“Well, Bill, you stay here and work along up the creek. I will drop Bob off up the creek about fifty yards. In some cases you may have to dig shallow trenches to stop the fire. In others the fire will stop itself when it reaches the green grass. We can keep the backfires under control and head them at the other fire. When the two meet our work is done. Get the idea?”

“How about the fire spreading west?” asked Bill.

“This creek runs into Cow Creek a couple of rods down,” said Sam. “Simmons has a whole flock of people working along Cow Creek.”

The backfires were started. To keep them headed in the right direction, Bill in some places cleared away the dried leaves, but in others it was not necessary, as the fires were started along the creek bank. At times he found entirely different conditions where he had to dig shallow trenches to confine the fire. Bob and Sam disappeared into the woods, leaving a trail of smoke and flame to mark their trail. Bill was alone. He was terribly tired, so tired that he could hardly move.

He threw himself on the ground to rest. It was cool lying there and so hot working with the shovel digging trenches. The walk had not been an easy one, either. For a few seconds he took things easy and enjoyed the cool shade by the stream. Then a burning snag fell to the ground a short distance away. It was so close that Bill could see the column of sparks mount almost indefinitely into the sky. The crash of that snag jerked Bill to his feet and back to his job.

The fires were now all along the creek and the smoke was blinding. At times the backfires became unruly and he had to work at full speed to keep them under control. The heat became intense and everything that he had on was soaking wet. His arms and shoulders were so fatigued that he could hardly move them, but he kept on working.

Bill looked down the stream toward where he had started and saw that the fire was dying out. This gave him confidence in the work that he was doing. He could see that he was getting results from his tiring efforts.

His hands, face and arms were covered with black from the flying ashes and partly burned particles of wood or leaves. His skin was burned by the heat of the fire. His hands were a mass of blisters from the shovel and axe. It was the hardest work that he had ever done. How long he had been at it, he did not know. It seemed as if hours had passed since Sam and Bob had disappeared in the smoke.

One after another of the backfires joined with its neighbor. They gradually extended farther and farther away from the creek until there was a broad black belt separating the creek from the main fire. The backfiring had been a success in that area if not in any other. The main fire could not get across a space which had already been burned.

Bill continued to work up the stream. Soon he came to a place where someone else had obviously worked on a backfire. When he was sure that there was a continuous line of burned ground along the stream in his area, he went back again to be sure that no new fires had started while he was gone. Everything was as he had left it. His first fire-fighting had been a success.

The main fire was much nearer, but Bill no longer felt any danger from that. Let it come, it could not pass the wall which he had built across its front. Bill sat down along the creek to cool off and rest while waiting for Sam and Bob to return.

It had been a long, hard day for Bill Bruce. He had fished all morning and had rested a while after lunch, but since the time that Cecil had left, he had been working hard. The automobile trip to Couch’s ranch had been only ten or fifteen miles and had lasted but a comparatively few minutes, but the hike through the woods and the fire-fighting were much different.

Exhausted by the hard hike through the underbrush and bushes, the manual labor of fighting the fire had completed the job and there was not a muscle in Bill’s body which did not ache and pain. He had no idea as to the time of day. The smoke had obscured the sunlight so that he could not estimate the hour, and he was too tired to even look at his watch. He didn’t care much, either.

As a matter-of-fact, it was late in the afternoon when he finally returned and sank down alongside the creek bank after his last patrol along the fire line. How long he had been sitting there he did not know, but it was beginning to get dark when he heard voices. The fire was gradually burning itself out. The sharp, ear-splitting crackling of the flames was much less audible. The smoke was just as thick as ever, but the terrifying aspect of the fire was gone. Simmons had done his job well. The fire had been conquered.

Bill recognized the voices as those of Crouch and Bob. He could not see them, but heard them talking as they approached the place where he was sitting. Bill jumped up in spite of his aching muscles.

“We left Bill along here somewhere,” said Crouch.

“Hello, Bill,” called Bob.

“Here I am,” replied Bill.

“Well, we did our part,” said Crouch when he came to where Bill was standing. “It looks to me as if the fire has lost all its dangers now. The men with Simmons can handle it from now on. Where is your car? If I remember correctly, you said that you were tourists.”

“Our car is down at your place,” said Bill.

“That’s fine,” remarked Crouch. “I know a trail through the woods along Oak Creek that leads out into the main road. By going that way we will not have to climb the ridge we came down.”

“The sooner the better,” said Bob. “You can’t get back to your place too soon to suit me.”

“What will we do with the forestry service tools?” asked Bill.

“Just bring them along,” said Crouch. “They will stop by my place and collect them when they come out.”

It was so easy to say, “Just bring them along,” but every added pound made Bill’s aching body feel like an open sore. He did not say anything, but raised the shovel and axe to his shoulders and stood ready to start. It was quite dark by this time, and following Crouch along the narrow trail was quite a task. The trail turned at all sorts of unlooked-for places. Limbs of trees and small bushes scratched his face and hands as they walked along. Once he ran into a tree before he saw it when the trail turned sharply.

Bill’s feet seemed so heavy that he doubted his ability to walk another step. He turned around to look at Bob and could not see him in the semi-darkness. That made him feel better. Bob must be as tired as he was. Sam Crouch was walking along with the same swing that he had used when they first met. The man was not human. It was physically impossible for a man to work as hard as they had for a whole afternoon and part of the evening and then be as fresh and energetic as Crouch was.

The trail through the woods seemed endless. Finally they reached the road and Bill hastened his steps to walk alongside of Crouch.

“Don’t you ever get tired?” asked Bill.

“Son, I have been doing this ever since I was seven years old,” replied Crouch. “This is just a routine day for me. I like the woods and am always waiting for an excuse to get away from people and communities. I probably would be better off if I didn’t spend so much time hunting and fishing, but the different game seasons come so close together that I don’t seem to have much time to do much else. Right now it is good fishing season. That will last pretty nearly all Summer. Then the salmon will start running up the river. Down in the valley we have good pheasant shooting. Occasionally we have wild pigeon shooting. In the Fall there is always good deer hunting. Then Winter comes along and I go out after bear and mountain lions. The snows shut me in for a while after that and I am forced to stay home for a few weeks. Taking it all in all, I do not have much time to work on my clearing.”

“That’s what I would call an ideal existence,” said Bill.

As they talked, Bob came up and walked along with them. It did not seem half as tiring when they were talking as when they apparently covered mile after mile in silence.

“Have you ever seen the salmon run?” asked Crouch.

“No, I never have,” replied Bill.

“If you get a chance, don’t miss it,” said Crouch. “By the way, where do you two fellows come from?”

“We are stationed in San Francisco,” replied Bill.

“You ought to get good fishing around there,” said Crouch.

“We haven’t been there long enough to get any fishing,” explained Bob. “We were stationed down in the Imperial Valley until a few weeks ago.”

“What are you fellows, anyway?” asked Crouch.

“We are in the Army,” said Bill. “We are in the Air Service.”

“Do you fly airplanes?”

“That’s our job,” replied Bob.

“I’d rather hunt bears,” said Crouch. “The highest that I want to get is up on the ‘poop deck’ of a horse. That’s far enough for me to fall. Well, here we are at the shack. What are you going to do now?”

“Take our car and hunt for a place to camp,” replied Bill.

“No use of your doing that. I am here all by myself. I haven’t any beds, but I can give you a room and you can spread out your blankets on a couple of old mattresses that I have and sleep in comfort. You must be tired and ought to get a good night’s rest. I can cook up some grub for supper and then you can turn in. What do you say?”

“It’s too good to be true,” said Bill. “If you hadn’t asked me to sleep in your house, I would have rolled up in my blanket out here by the car and slept on the ground. I am just that tired. That was a mighty big fire, wasn’t it?”

“Just a baby,” replied Sam. “Only about eight or nine hundred acres. Why some of them cover that many thousand acres and we have several at the same time.”

“I’ll get out blankets and bags while you help get supper,” said Bob to Bill as they reached the house.

Supper, the laying of their beds and the short talk after supper were like a dream to Bill. Both he and Bob were asleep as soon as they landed between their blankets.

“Say, are you fellows going to sleep all day?”

Bill sat up. The sun was shining into the room. It was late in the morning. His muscles were sore and he was stiff all over. Every movement that he made started new pains through his body.

“I thought that we might go fishing this morning,” said Crouch.

“That’s an idea at that,” said Bill. “Bob, wake up, we are going fishing.”

“You go fishing and let me sleep,” said Bob drowsily.

“Come on, breakfast is on the table,” said Crouch.

“All right, if I must,” replied Bob. “I don’t feel much like it, though.”

“All the stiffness and soreness will be gone after we have been out for a few minutes,” said Crouch.

So the days passed. The young aviators stayed several days with Sam Crouch and learned more about wood life and the art of fishing than they could have learned in several months by themselves. Finally the time came when they wanted to push farther up into the woods. It was hard to say good-bye to Sam, but they finally did, promising to look him up again whenever they came back that way.

“Here’s something to take with you,” said Sam as they were about to start away.

Sam handed them a glass jar. Bill looked to see what it contained, but could not determine anything from its appearance. Obviously it was some kind of dried meat. Sam saw the inquiry in Bill’s expression.

“It’s jerkey,” explained Sam.

“What’s that?” asked Bill.

“You don’t know what jerkey is?”

“Never heard of it,” replied Bob.

“I can’t eat all the deer meat that I get during the hunting season, so I dry it for future use,” said Sam. “This is dried venison. I think that you will like chewing it while you are fishing.”

“Thanks very much,” said Bill and Bob in unison as they started away.

That night they camped several miles away from Sam Crouch’s clearing. As far as they could see, there was no settlement within miles. The fishing was good and they were more than satisfied when they finished their supper.

“This is really our first night out,” said Bill. “We started out with the idea that we would camp every night, but have never done it before. What will we do with our stuff?”

“Just leave everything as it is until morning,” replied Bob. “There’s no one anywhere around here.”

“I don’t know whether that is the proper thing to do,” replied Bill. “I guess that it doesn’t make any difference, though, for we have to start back home tomorrow.”

The boys rolled up in their blankets and were soon asleep. Bill was later awakened by the sound of something moving around his clothes. He sat up and threw the beam of his flashlight around. It finally rested upon an animal the likes of which he had never seen before. The animal was eating or nibbling one of his leggins. Bill jumped up, and with the movement there was no doubt as to the identity of the animal. It raised its quills until it looked like a large thistle.

“Bob,” called Bill. “Here’s a porcupine.”

“Where?” asked Bob as he sat up.

The porcupine made no attempt to move away in spite of all the noise. It sat quietly as if it were in its own domain. The only difference was that it had stopped nibbling on the leather leggins. The aviators knew that they could not catch it in their hands, so looked around for something to wrap around it. While they were searching, the porcupine ambled away and was soon lost in the darkness.

“Well, he got away,” said Bill, as they again rolled themselves in their blankets.

“He would have made a good mascot for the squadron,” said Bob.

“Unique but rather sticky,” said Bill as he dropped off to sleep.

About an hour later Bill was awakened again. He had the feeling that there was something rummaging in the camp equipage. He threw his flashlight in the general direction of where the supplies were piled and was almost frozen stiff with fright at what he saw.

A large brown bear was mauling among the boxes and cans trying hard to find something to eat. Not far off another bear was delving in the garbage pit. Then there was a terrible crashing and smashing as the first bear vented its rage against the pots, pans, and kettles. This woke Bob.

“What’s all the noise?” asked Bob.

Bill didn’t know whether to answer or to keep quiet. The bears were but a few feet away. If he said anything, it might attract the attention of the bears. If he didn’t, Bob might call out again and then that would attract them. At the present time they were busily engaged in wrecking the camp and were not interested in either the flashlight or Bob’s talking.

Bob did not need to get an answer to his question, for he looked in the beam of the flashlight and saw what was going on. What was to be done now? Neither one of the two young airmen could answer the question. Bill finally decided that something must be done, so jumped up and began clapping his hands and shouting.

The bear at the garbage pit stood up, but stayed where it was. It looked as large as a house to Bill, so he stopped in his tracks wondering whether to run toward or away from the bear. The other bear ambled off a few feet and then turned around to watch the proceedings. For a long time both Bill and the bear stood watching each other.

Bill again started shouting and then made another short dash after the nearest bear. It walked slowly away for a few more feet and then stopped and turned around. Bill began to lose his bravery just then, for the bear seemed to look him straight in the eye. The effect on the second bear was entirely different, for it made a dash to get away. The direction it took was rather unfortunate for Bob, for the bear headed right at Bob.

Evidently it did not see Bob stretched out on the ground, but Bob saw the bear coming and dropped down flat in his blankets. The bear did not have any designs against Bob, however, for it cleared him with a bound and was off in the woods. The shout that Bob gave as the bear reached his blankets was too much for the first one and it ambled off and disappeared in the thickets.

“This is no place for a white man,” said Bob after the bears had both gone. “I am in favor of packing up and getting out right now.”

“That’s all right with me,” replied Bill. “But I don’t think that they will come back. I think that they are gone for the night.”

“You can stay here if you want to, but not for mine; I’m on my way,” said Bob.

“Well, we might as well move on,” said Bill after looking at his watch. “It’s only a couple of hours until daylight and that will give us a good start.”

“Our vacation in the woods is over,” said Bob “Now we go back to our routine flying.”

“We have had a wonderful time, though, and I am coming back,” said Bill. “I am going to find out from Sam the next time, though, what to do when bears invade our camp.”

They started back to San Francisco very much impressed with the life in the forests. Each was determined to return as soon as he could, but neither realized that they would return almost as soon as they joined their squadron, but with an entirely different reason for the visit.

“How did you enjoy your life in the woods?” asked Captain Smith when Bill Bruce and Bob Finch reported for duty at the flying field at the Presideo at San Francisco.

“We had a fine time and found it very educational,” replied Bill. “I never knew that there were so many different kinds of trees. We were very fortunate in meeting Mr. George Cecil, the District Forester. He is in charge of all the National Forests in Oregon and Washington. We probably would have run into all kinds of trouble if he hadn’t given us a start in the customs and manners of life in the woods. Then we were drafted to fight a forest fire, and say, boy, if you want to get action, join a forest fire-fighting gang. It is hard work, but the terrifying, destructive grandeur of a forest fire is beyond description.”

“You didn’t enjoy it any more than I did when those bears raided our camp when we were asleep,” interjected Bob. “I wasn’t the only one who was ready to start back home.”

“I must admit that our education was not quite complete in that respect,” admitted Bill. “Before I go out again, I am going to get someone to tell me what to do when a bear romps through your camp after dark.”

“What did you do?” asked Smith.

“Just what a normal man would do,” replied Bill. “I was scared to death when I saw the first bear and more scared when I saw the second one, but I tried not to show it.”

“You have been having a vacation, and now you will have to get back to work,” said Captain Smith. “We are observing the fire of the coast defense guns this morning. Bruce will take the first shoot and Finch, you take the second one. Sergeant Breene can use the radio, but you had better give him your sensings of the positions of the shots with reference to the target before he sends them down. You can get some idea as to the distance the shot falls from the target by the length of the cable between the target and the tug. You will shove off in half an hour. Your plane is having a new engine installed so that you will have to use Batten’s.”

“I don’t know much about artillery adjustment,” said Bill. “During the war I was a pursuit pilot.”

“Now’s the best time to learn then,” replied Smith.

“Why the trick leggins?” asked Kiel, the Commander of the Second Flight in the Ninth Squadron.

“I had no choice,” replied Bill. “A porcupine started to eat my best ones while I was up in Oregon. All my others need cleaning too badly to wear. These wrapped leggins are comfortable, even though they take more time to put on.”

“I thought that everyone threw away those leggins as soon as they could after the war,” said Kiel.

“It’s a good thing that I saved these,” replied Bill. “If I hadn’t, I would have been waiting in my quarters now for my others to be shined and repaired. Then you would have had to take this mission. From my point of view, I would rather have had it that way.”

“Well, Sergeant, how’s the old bus percolating?” asked Bill when he came out onto the line and met Sergeant Breene.

“A new engine is being installed in yours,” replied Breene.

“I know that, but how is Lieutenant Batten’s? That’s the one that you and I are going to take out on this artillery mission.”

“I don’t know anything about his plane,” replied Breene. “His crew chief takes care of it.”

“Well, get your flying togs, for we take off as soon as we can get the bus warmed up.”

In a few minutes they were flying around over the reservation while they checked their radio with the ground station at the airdrome. The antenna wire hung two hundred feet below the plane and formed an arc with the lead “fish” at the end of the wire. The fish was a weight shaped in a stream line form so that the wire would ride steadily through the air and hang well down below the plane.