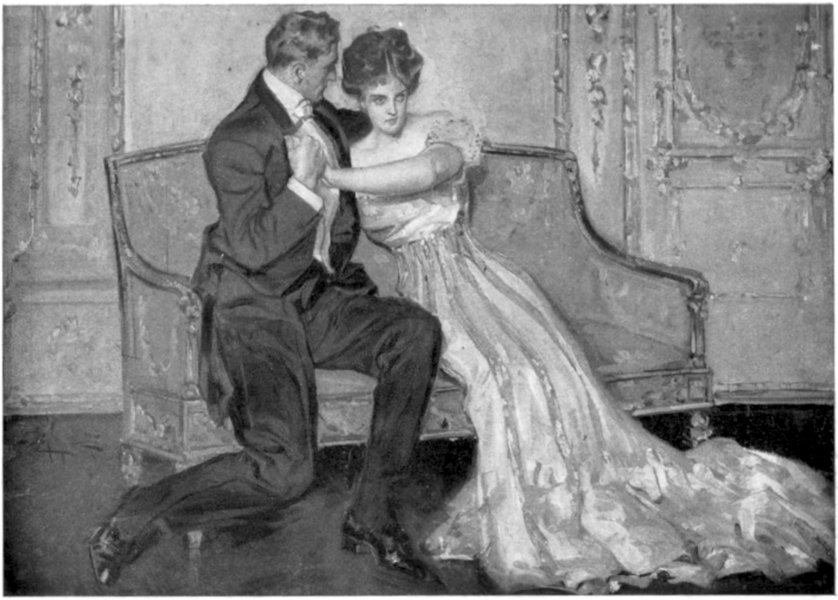

"I will teach you to love me," he cried.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Grain Of Dust, by David Graham Phillips

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Grain Of Dust

A Novel

Author: David Graham Phillips

Release Date: December 15, 2004 [EBook #430]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GRAIN OF DUST ***

Produced by Charles Keller and David Garcia

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

"'I will teach you to love me,' he cried."

"'You won't make an out-and-out idiot of yourself, will you Ursula?'"

"'It has killed me,' he groaned."

"She glanced complacently down at her softly glistening shoulders."

"'Father ... I have asked you not to interfere between Fred and me.'"

"Evidently she had been crying."

"At Josephine's right sat a handsome young foreigner."

Into the offices of Lockyer, Sanders, Benchley, Lockyer & Norman, corporation lawyers, there drifted on a December afternoon a girl in search of work at stenography and typewriting. The firm was about the most important and most famous—radical orators often said infamous—in New York. The girl seemed, at a glance, about as unimportant and obscure an atom as the city hid in its vast ferment. She was blonde—tawny hair, fair skin, blue eyes. Aside from this hardly conclusive mark of identity there was nothing positive, nothing definite, about her. She was neither tall nor short, neither fat nor thin, neither grave nor gay. She gave the impression of a young person of the feminine gender—that, and nothing more. She was plainly dressed, like thousands of other girls, in darkish blue jacket and skirt and white shirt waist. Her boots and gloves were neat, her hair simply and well arranged. Perhaps in these respects—in neatness and taste—she did excel the average, which is depressingly low. But in a city where more or less strikingly pretty women, bent upon being seen, are as plentiful as the blackberries of Kentucky's July—in New York no one would have given her a second look, this quiet young woman screened in an atmosphere of self-effacement.

She applied to the head clerk. It so happened that need for another typewriter had just arisen. She got a trial, showed enough skill to warrant the modest wage of ten dollars a week; she became part of the office force of twenty or twenty-five young men and women similarly employed. As her lack of skill was compensated by industry and regularity, she would have a job so long as business did not slacken. When it did, she would be among the first to be let go. She shrank into her obscure niche in the great firm, came and went in mouse-like fashion, said little, obtruded herself never, was all but forgotten.

Nothing could have been more commonplace, more trivial than the whole incident. The name of the girl was Hallowell—Miss Hallowell. On the chief clerk's pay roll appeared the additional information that her first name was Dorothea. The head office boy, in one of his occasional spells of "freshness," addressed her as Miss Dottie. She looked at him with a puzzled expression; it presently changed to a slight, sweet smile, and she went about her business. There was no rebuke in her manner, she was far too self-effacing for anything so positive as the mildest rebuke. But the head office boy blushed awkwardly—why he did not know and could not discover, though he often cogitated upon it. She remained Miss Hallowell.

Opposites suggest each other. The dimmest personality in those offices was the girl whose name imaged to everyone little more than a pencil, notebook, and typewriting machine. The vividest personality was Frederick Norman. In the list of names upon the outer doors of the firm's vast labyrinthine suite, on the seventeenth floor of the Syndicate Building, his name came last—and, in the newest lettering, suggesting recentness of partnership. In age he was the youngest of the partners. Lockyer was archaic, Sanders an antique; Benchley, actually only about fifty-five, had the air of one born in the grandfather class. Lockyer the son dyed his hair and affected jauntiness, but was in fact not many years younger than Benchley and had the stiffening jerky legs of one paying for a lively youth. Norman was thirty-seven—at the age the Greeks extolled as divine because it means all the best of youth combined with all the best of manhood. Some people thought Norman younger, almost boyish. Those knew him uptown only, where he hid the man of affairs beneath the man of the world-that-amuses-itself. Some people thought he looked, and was, older than the age with which the biographical notices credited him. They knew him down town only—where he dominated by sheer force of intellect and will.

As has been said, the firm ranked among the greatest in New York. It was a trusted counselor in large affairs—commercial, financial, political—in all parts of America, in all parts of the globe, for many of its clients were international traffickers. Yet this young man, this youngest and most recent of the partners, had within the month forced a reorganization of the firm—or, rather, of its profits—on a basis that gave him no less than one half of the whole.

His demand threw his four associates into paroxysms of rage and fear—the fear serving as a wholesome antidote to the rage.

It certainly was infuriating that a youth, admitted to partnership barely three years ago, should thus maltreat his associates. Ingrate was precisely the epithet for him. At least, so they honestly thought, after the quaint human fashion; for, because they had given him the partnership, they looked on themselves as his benefactors, and neglected as unimportant detail the sole and entirely selfish reason for their graciousness. But enraged though these worthy gentlemen were, and eagerly though they longed to treat the "conceited and grasping upstart" as he richly deserved, they accepted his ultimatum. Even the venerable and venerated Lockyer—than whom a more convinced self-deceiver on the subject of his own virtues never wore white whiskers, black garments, and the other badges of eminent respectability—even old Joseph Lockyer could not twist the acceptance into another manifestation of the benevolence of himself and his associates. They had to stare the grimacing truth straight in the face; they were yielding because they dared not refuse. To refuse would mean the departure of Norman with the firm's most profitable business. It costs heavily to live in New York; the families of successful men are extravagant; so conduct unbecoming a gentleman may not there be resented if to resent is to cut down one's income. The time was, as the dignified and nicely honorable Sanders observed, when these and many similar low standards did not prevail in the legal profession. But such is the frailty of human nature—or so savage the pressure of the need of the material necessities of civilized life, let a profession become profitable or develop possibilities of profit—even the profession of statesman, even that of lawyer—or doctor—or priest—or wife—and straightway it begins to tumble down toward the brawl and stew of the market place.

In a last effort to rouse the gentleman in Norman or to shame him into pretense of gentlemanliness, Lockyer expostulated with him like a prophet priest in full panoply of saintly virtue. And Lockyer was passing good at that exalted gesture. He was a Websterian figure, with the venality of the great Daniel in all its pompous dignity modernized—and correspondingly expanded. He abounded in those idealist sonorosities that are the stock-in-trade of all solemn old-fashioned frauds. The young man listened with his wonted attentive courtesy until the dolorous appeal disguised as fatherly counsel came to an end. Then in his blue-gray eyes appeared the gleam that revealed the tenacity and the penetration of his mind. He said:

"Mr. Lockyer, you have been absent six years—except an occasional two or three weeks—absent as American Ambassador to France. You have done nothing for the firm in that time. Yet you have not scorned to take profits you did not earn. Why should I scorn to take profits I do earn?"

Mr. Lockyer shook his picturesque head in sad remonstrance at this vulgar, coarse, but latterly frequent retort of insurgent democracy upon indignant aristocracy. But he answered nothing.

"Also," proceeded the graceless youth in the clear and concise way that won the instant attention of juries and Judges, "also, our profession is no longer a profession but a business." His humorous eyes twinkled merrily. "It divides into two parts—teaching capitalists how to loot without being caught, and teaching them how to get off if by chance they have been caught. There are other branches of the profession, but they're not lucrative, so we do not practice them. Do I make myself clear?"

Mr. Lockyer again shook his head and sighed.

"I am not an Utopian," continued young Norman. "Law and custom permit—not to say sanctify—our sort of business. So—I do my best. But I shall not conceal from you that it's distasteful to me. I wish to get out of it. I shall get out as soon as I've made enough capital to assure me the income I have and need. Naturally, I wish to gather in the necessary amount as speedily as possible."

"Fred, my boy, I regret that you take such low views of our noble profession."

"Yes—as a profession it is noble. But not as a practice. My regret is that it invites and compels such low views."

"You will look at these things more—more mellowly when you are older."

"I doubt if I'll ever rise very high in the art of self-deception," replied Norman. "If I'd had any bent that way I'd not have got so far so quickly."

It was a boastful remark—of a kind he, and other similar young men, have the habit of making. But from him it did not sound boastful—simply a frank and timely expression of an indisputable truth, which indeed it was. Once more Mr. Lockyer sighed. "I see you are incorrigible," said he.

"I have not acted without reflection," said Norman.

And Lockyer knew that to persist was simply to endanger his dignity. "I am getting old," said he. "Indeed, I am old. I have gotten into the habit of leaning on you, my boy. I can't consent to your going, hard though you make it for us to keep you. I shall try to persuade our colleagues to accept your terms."

Norman showed neither appreciation nor triumph. He merely bowed slightly. And so the matter was settled. Instead of moving into the suite of offices in the Mills Building on which he had taken an option, young Norman remained where he had been toiling for twelve years.

After this specimen of Norman's quality, no one will be surprised to learn that in figure he was one of those solidly built men of medium height who look as if they were made to sustain and to deliver shocks, to bear up easily under heavy burdens; or that his head thickly covered with fairish hair, was hatchet-shaped with the helve or face suggesting that while it could and would cleave any obstacle, it would wear a merry if somewhat sardonic smile the while. No one had ever seen Norman angry, though a few persevering offenders against what he regarded as his rights had felt the results of swift and powerful action of the same sort that is usually accompanied—and weakened—by outward show of anger. Invariably good-humored, he was soon seen to be more dangerous than the men of flaring temper. In most instances good humor of thus unbreakable species issues from weakness, from a desire to conciliate—usually with a view to plucking the more easily. Norman's good humor arose from a sense of absolute security which in turn was the product of confidence in himself and amiable disdain for his fellow men. The masses he held in derision for permitting the classes to rule and rob and spit upon them. The classes he scorned for caring to occupy themselves with so cheap and sordid a game as the ruling, robbing, and spitting aforesaid. Coming down to the specific, he despised men as individuals because he had always found in each and everyone of them a weakness that made it easy for him to use them as he pleased.

Not an altogether pleasant character, this. But not so unpleasant as it may seem to those unable impartially to analyze human character, even their own—especially their own. And let anyone who is disposed to condemn Norman first look within himself—in some less hypocritical and self-deceiving moment, if he have such moments—and let him note what are the qualities he relies upon and uses in his own struggle to save himself from being submerged and sunk. Further, there were in Norman many agreeable qualities, important, but less fundamental, therefore less deep-hidden—therefore generally regarded as the real man and as the cause of his success in which they in fact had almost no part. He was, for example, of striking physical appearance, was attractively dressed and mannered, was prodigally generous. Neither as lawyer nor as man did he practice justice. But while as lawyer he practiced injustice, as man he practiced mercy. Whenever a weakling appealed to him for protection, he gave it—at times with splendid recklessness as to the cost to himself in antagonisms and enmities. Indeed, so great were the generosities of his character that, had he not been arrogant, disdainful, self-confident, resolutely and single-heartedly ambitious, he must inevitably have ruined himself—if he had ever been able to rise high enough to be worthy the dignity of catastrophe.

Successful men are usually trying persons to know well. Lambs, asses, and chickens do not associate happily with lions, wolves, and hawks—nor do birds and beasts of prey get on well with one another. Norman was regarded as "difficult" by his friends—by those of them who happened to get into the path of his ambition, in front of instead of behind him, and by those who fell into the not unnatural error of misunderstanding his good nature and presuming upon it. His clients regarded him as insolent. The big businesses, seeking the rich spoils of commerce, frequent highly perilous waters. They need skillful pilots. Usually these lawyer-pilots "know their place" and put on no airs upon the quarter-deck while they are temporarily in command. Not so Norman. He took the full rank, authority—and emoluments—of commander. And as his power, fame, and income were swiftly growing, it is fair to assume that he knew what he was about.

He was admired—extravagantly admired—by young men with not too broad a vein of envy. He was no woman hater—anything but that. Indeed, those who wished him ill had from time to time hoped to see him tumble down, through miscalculation in some of his audacities with women. No—he did not hate women. But there were several women who hated him—or tried to; and if wounded vanity and baffled machination be admitted as just causes for hatred, they had cause. He liked—but he did not wholly trust. When he went to sleep, it was not where Delilah could wield the shears. A most irritating prudence—irritating to friends and intimates of all degrees and kinds, in a race of beings with a mania for being trusted implicitly but with no balancing mania for deserving trust of the implicit variety.

And he ate hugely—and whatever he pleased. He could drink beyond belief, all sorts of things, with no apparent ill effect upon either body or brain. He had all the appetites developed abnormally, and abnormal capacity for gratifying them. Where there was one man who envied him his eminence, there were a dozen who envied him his physical capacities. We cannot live and act without doing mischief, as well as that which most of us would rather do, provided that in the doing we are not ourselves undone. Probably in no direction did Norman do so much mischief as in unconsciously leading men of his sets down town and up to imitate his colossal dissipations—which were not dissipation for him who was abnormal.

Withal, he was a monster for work. There is not much truth in men's unending talk of how hard they work or are worked. The ravages from their indulgences in smoking, drinking, gallantry, eating too much and too fast and too often, have to be explained away creditably, to themselves and to others—notably to the wives or mothers who nurse them and suffer from their diminishing incomes. Hence the wailing about work. But once in a while a real worker appears—a man with enormous ingenuity at devising difficult tasks for himself and with enormous persistence in doing them. Frederick Norman was one of these blue-moon prodigies.

Obviously, such a man could not but be observed and talked about. Endless stories, some of them more or less true, most of them apocryphal, were told of him—stories of his shrewd, unexpected moves in big cases, of his witty retorts, of his generosities, of his peculiarities of dress, of eating and drinking; stories of his adventures with women. Whatever he did, however trivial, took color and charm from his personality, so easy yet so difficult, so simple yet so complex, so baffling. Was he wholly selfish? Was he a friend to almost anybody or to nobody? Did he ever love? No one knew, not even himself, for life interested him too intensely and too incessantly to leave him time for self-analysis. One thing he was certain of; he hated nobody, envied nobody. He was too successful for that.

He did as he pleased. And, on the whole, he pleased to do far less inconsiderately than his desires, his abilities, and his opportunities tempted. Have not men been acclaimed good for less?

In the offices, where he was canvased daily by partners, clerks, everyone down to the cleaners whose labors he so often delayed, opinion varied from day to day. They worshiped him; they hated him. They loved him; they feared him. They regarded him as more than human, as less than human; but never as just human—though always as endowed with fine human virtues and even finer human weaknesses. Miss Tillotson, next to the head clerk in rank and pay—and a pretty and pushing young person—dreamed of getting acquainted with him—really well acquainted. It was a vain dream. For him, between up town and down town a great gulf was fixed. Also, he had no interest in or ammunition for sparrows.

It was in December that Miss Hallowell—Miss Dorothea Hallowell—got her temporary place at ten dollars a week—that obscure event, somewhat like a field mouse taking quarters in a horizon-bounded grain field. It was not until mid-February that she, the palest of personalities, came into direct contact with Norman, about the most refulgent. This is how it happened.

Late in that February afternoon, an hour or more after the last of the office force should have left, Norman threw open the door of his private office and glanced round at the rows on rows of desks. The lights in the big room were on, apparently only because he was still within. With an exclamation of disappointment he turned to re-enter his office. He heard the click of typewriter keys. Again he looked round, but could see no one.

"Isn't there some one here?" he cried. "Don't I hear a typewriter?"

The noise stopped. There was a slight rustling from a far corner, beyond his view, and presently he saw advancing a slim and shrinking slip of a girl with a face that impressed him only as small and insignificant. In a quiet little voice she said, "Yes, sir. Do you wish anything?"

"Why, what are you doing here?" he asked. "I don't think I've ever seen you before."

"Yes. I took dictation from you several times," replied she.

He was instantly afraid he might have hurt her feelings, and he, who in the days when he was far, far less than now, had often suffered from that commonplace form of brutality, was most careful not to commit it. "I never know what's going on round me when I'm thinking," explained he, though he was saying to himself that the next time he would probably again be unable to remember one with nothing distinctive to fix identity. "You are—Miss——?"

"Miss Hallowell."

"How do you happen to be here? I've given particular instructions that no one is ever to be detained after hours."

A little color appeared in the pale, small face—and now he saw that she had a singularly fair and smooth skin, singularly beautiful—and he wondered why he had not noticed it before. Being a close observer, he had long ago noted and learned to appreciate the wonders of that most amazing of tissues, the human skin; and he had come to be a connoisseur. "I'm staying of my own accord," said she.

"They ought not to give you so much work," said he. "I'll speak about it."

Into the small face came the look of the frightened child—a fascinating look. And suddenly he saw that she had lovely eyes, clear, expressive, innocent. "Please don't," she pleaded, in the gentle quiet voice. "It isn't overwork. I did a brief so badly that I was ashamed to hand it in. I'm doing it again."

He laughed, and a fine frank laugh he had when he was in the mood. At once a smile lighted up her face, danced in her eyes, hovered bewitchingly about her lips—and he wondered why he had not at first glance noted how sweet and charmingly fresh her mouth was. "Why, she's beautiful," he said to himself, the manly man's inevitable interest in feminine charm wide awake. "Really beautiful. If she had a figure—and were tall—" As he thought thus, he glanced at her figure. A figure? Tall? She certainly was tall—no, she wasn't—yes, she was. No, not tall from head to foot, but with the most captivating long lines—long throat, long bust, long arms, long in body and in legs—long and slender—yet somehow not tall. He—all this took but an instant—returned his glance to her face. He was startled. The beauty had fled, leaving not a trace behind. Before him wavered once more a small insignificance. Even her skin now seemed commonplace.

She was saying, "Did you wish me to do something?"

"Yes—a letter. Come in," he said abruptly.

Once more the business in hand took possession of his mind. He became unconscious of her presence. He dictated slowly, carefully choosing his words, for perhaps a quarter of an hour. Then he stopped and paced up and down, revolving a new idea, a new phase of the business, that had flashed upon him. When he had his thoughts once more in form he turned toward the girl, the mere machine. He gazed at her in amazement. When he had last looked, he had seen an uninteresting nonentity. But that was not this person, seated before him in the same garments and with the same general blondness. That person had been a girl. This time the transformation was not into the sweet innocence of lovely childhood, but into something incredibly different. He was gazing now at a woman, a beautiful world-weary woman, one who had known the joys and then the sorrows of life and love. Heavy were the lids of the large eyes gazing mournfully into infinity—gazing upon the graves of a life, the long, long vista of buried joys. Never had he seen anything so sad or so lovely as her mouth. The soft, smooth skin was not merely pale; its pallor was that of wakeful nights, of weeping until there were no more tears to drain away.

"Miss Hallowell—" he began.

She startled; and like the flight of an interrupted dream, the woman he had been seeing vanished. There sat the commonplace young person he had first seen. He said to himself: "I must be a little off my base to-night," and went on with the dictation. When he finished she withdrew to transcribe the letter on the typewriter. He seated himself at his desk and plunged into the masses of documents. He lost the sense of his surroundings until she stood beside him holding the typewritten pages. He did not glance up, but seized the sheets to read and sign.

"You may go," said he. "I am very much obliged to you." And he contrived, as always, to put a suggestion of genuineness into the customary phrase.

"I'm afraid it's not good work," said she. "I'll wait to see if I am to do any of it over."

"No, thank you," said he. And he looked up—to find himself gazing at still another person, wholly different from any he had seen before. The others had all been women—womanly women, full of the weakness, the delicateness rather, that distinguishes the feminine. This woman he was looking at now had a look of strength. He had thought her frail. He was seeing a strong woman—a splendidly healthy body, with sinews of steel most gracefully covered by that fair smooth skin of hers. And her features, too—why, this girl was a person of character, of will.

He glanced through the pages. "All right—thank you," he said hastily. "Please don't stay any longer. Leave the other thing till to-morrow."

"No—it has to be done to-night."

"But I insist upon your going."

She hesitated, said quietly, "Very well," and turned to go.

"And you mustn't do it at home, either."

She made no reply, but waited respectfully until it was evident he wished to say no more, then went out. He bundled together his papers, sealed and stamped and addressed his letter, put on his overcoat and hat and crossed the outer office on his way to the door. It was empty; she was gone. He descended in the elevator to the street, remembered that he had not locked one of his private cases, returned. As he opened the outer door he heard the sound of typewriter keys. In the corner, the obscure, sheltered corner, sat the girl, bent with childlike gravity over her typewriter. It was an amusing and a touching sight—she looked so young and so solemnly in earnest.

"Didn't I tell you to go home?" he called out, with mock sternness.

Up she sprang, her hand upon her heart. And once more she was beautiful, but once more it was in a way startlingly, unbelievably different from any expression he had seen before.

"Now, really. Miss—" He had forgotten her name. "You must not stay on here. We aren't such slave drivers as all that. Go home, please. I'll take the responsibility."

She had recovered her equanimity. In her quiet, gentle voice—but it no longer sounded weak or insignificant—she said, "You are very kind, Mr. Norman. But I must finish my work."

"Haven't I said I'd take the blame?"

"But you can't," replied she. "I work badly. I seem to learn slowly. If I fall behind, I shall lose my place—sooner or later. It was that way with the last place I had. If you interfered, you'd only injure me. I've had experience. And—I must not lose my place."

One of the scrub women thrust her mussy head and ragged, shapeless body in at the door. With a start Norman awoke to the absurdity of his situation—and to the fact that he was placing the girl in a compromising position. He shrugged his shoulders, went in and locked the cabinet, departed.

"What a queer little insignificance she is!" thought he, and dismissed her from mind.

Many and fantastic are the illusions the human animal, in its ignorance and its optimism, devises to change life from a pleasant journey along a plain road into a fumbling and stumbling and struggling about in a fog. Of these hallucinations the most grotesque is that the weak can come together, can pass a law to curb the strong, can set one of their number to enforce it, may then disperse with no occasion further to trouble about the strong. Every line of every page of history tells how the strong—the nimble-witted, the farsighted, the ambitious—have worked their will upon their feebler and less purposeful fellow men, regardless of any and all precautions to the contrary. Conditions have improved only because the number of the strong has increased. With so many lions at war with each other not a few rabbits contrive to avoid perishing in the nest.

Norman's genius lay in ability to take away from an adversary the legal weapons implicitly relied upon and to arm his client with them. No man understood better than he the abysmal distinction between law and justice; no man knew better than he how to compel—or to assist—courts to apply the law, so just in the general, to promoting injustice in the particular. And whenever he permitted conscience a voice in his internal debates—it was not often—he heard from it its usual servile approbation: How can the reign of justice be more speedily brought about than by making the reign of law—lawyer law—intolerable?

About a fortnight after the trifling incident related in the previous chapter, Norman had to devise a secret agreement among several of the most eminent of his clients. They wished to band together, to do a thing expressly forbidden by the law; they wished to conspire to lower wages and raise prices in several railway systems under their control. But none would trust the others; so there must be something in writing, laid away in a secret safety deposit box along with sundry bundles of securities put up as forfeit, all in the custody of Norman. When he had worked out in his mind and in fragmentary notes the details of their agreement, he was ready for some one to do the clerical work. The some one must be absolutely trustworthy, as the plain language of the agreement would make clear to the dullest mind dazzling opportunities for profit—not only in stock jobbing but also in blackmail. He rang for Tetlow, the head clerk. Tetlow—smooth and sly and smug, lacking only courageous initiative to make him a great lawyer, but, lacking that, lacking all—Tetlow entered and closed the door behind him.

Norman leaned back in his desk chair and laced his fingers behind his head. "One of your typewriters is a slight blonde girl—sits in the corner to the far left—if she's still here."

"Miss Hallowell," said Tetlow. "We are letting her go at the end of this week. She's nice and ladylike, and willing—in fact, most anxious to please. But the work's too difficult for her. She's rather—rather—well, not exactly stupid, but slow."

"Um," said Norman reflectively. "There's Miss Bostwick—perhaps she'll do."

"Miss Bostwick got married last week."

Norman smiled. He remembered the girl because she was the oldest and homeliest in the office. "There's somebody for everybody—eh, Tetlow?"

"He was a lighthouse keeper," said Tetlow. "There's a story that he advertised for a wife. But that may be a joke."

"Why not that Miss—Miss Halloway?" mused Norman.

"Miss Hallowell," corrected Tetlow.

"Hallowell—yes. Is she—very incompetent?

"Not exactly that. But business is slackening—and she's been only temporary—and——"

Norman cut him off with, "Send her in."

"You don't wish her dismissed? I haven't told her yet."

"Oh, I'm not interfering in your department. Do as you like. . . . No—in this case—let her stay on for the present."

"I can use her," said Tetlow. "And she gets only ten a week."

Norman frowned. He did not like to hear that an establishment in which he had control paid less than decent living wages—even if the market price did excuse—yes, compel it. "Send her in," he repeated. Then, as Tetlow was about to leave, "She is trustworthy?"

"All our force is. I see to that, Mr. Norman."

"Has she a young man—steady company, I think they call it?"

"She has no friends at all. She's extremely shy—at least, reserved. Lives with her father, an old crank of an analytical chemist over in Jersey City. She hasn't even a lady friend."

"Well, send her in."

A moment later Norman, looking up from his work, saw the dim slim nonentity before him. Again he leaned back and, as he talked with her, studied her face to make sure that his first judgment was correct. "Do you stay late every night?" asked he smilingly.

She colored a little, but enough to bring out the exquisite fineness of her white skin. "Oh, I don't mind," said she, and there was no embarrassment in her manner. "I've got to learn—and doing things over helps."

"Nothing equal to it," declared Norman. "You've been to school?"

"Only six weeks," confessed she. "I couldn't afford to stay longer."

"I mean the other sort of school—not the typewriting."

"Oh! Yes," said she. And once more he saw that extraordinary transformation. She became all in an instant delicately, deliciously lovely, with the moving, in a way pathetic loveliness of sweet children and sweet flowers. Her look was mystery; but not a mystery of guile. She evidently did not wish to have her past brought to view; but it was equally apparent that behind it lay hid nothing shameful, only the sad, perhaps the painful. Of all the periods of life youth is the best fitted to bear deep sorrows, for then the spirit has its full measure of elasticity. Yet a shadow upon youth is always more moving than the shadows of maturer years—those shadows that do not lie upon the surface but are heavy and corroding stains. When Norman saw this shadow upon her youth, so immature-looking, so helpless-looking, he felt the first impulse of genuine interest in her. Perhaps, had that shadow happened to fall when he was seeing her as the commonplace and colorless little struggler for bread, and seeming doomed speedily to be worsted in the struggle—perhaps, he would have felt no interest, but only the brief qualm of pity that we dare not encourage in ourselves, on a journey so beset with hopeless pitiful things as is the journey through life.

But he had no impulse to question her. And with some surprise he noted that his reason for refraining was not the usual reason—unwillingness uselessly to add to one's own burdens by inviting the mournful confidences of another. No, he checked himself because in the manner of this frail and mouselike creature, dim though she once more was, there appeared a dignity, a reserve, that made intrusion curiously impossible. With an apologetic note in his voice—a kind and friendly voice—he said:

"Please have your typewriter brought in here. I want you to do some work for me—work that isn't to be spoken of—not even to Mr. Tetlow." He looked at her with grave penetrating eyes. "You will not speak of it?"

"No," replied she, and nothing more. But she accompanied the simple negative with a clear and honest sincerity of the eyes that set his mind completely at rest. He felt that this girl had never in her life told a real lie.

One of the office boys installed the typewriter, and presently Norman and the quiet nebulous girl at whom no one would trouble to look a second time were seated opposite each other with the broad table desk between, he leaning far back in his desk chair, fingers interlocked behind his proud, strong-looking head, she holding sharpened pencil suspended over the stenographic notebook. Long before she seated herself he had forgotten her except as machine. There followed a troubled hour, as he dictated, ordered erasure, redictated, ordered re-readings, skipped back and forth, in the effort to frame the secret agreement in the fewest and simplest, and least startlingly unlawful, words. At last he leaned forward with the shine of triumph in his eyes.

"Read straight through," he commanded.

She read, interrupted occasionally by a sharp order from him to correct some mistake in her notes.

"Again," he commanded, when she translated the last of her notes.

This time she was not interrupted once. When she ended, he exclaimed: "Good! I don't see how you did it so well."

"Nor do I," said she.

"You say you are only a beginner."

"I couldn't have done it so well for anyone else," said she. "You are—different."

The remark was worded most flatteringly, but it did not sound so. He saw that she did not herself understand what she meant by "different." He understood, for he knew the difference between the confused and confusing ordinary minds and such an intelligence as his own—simple, luminous, enlightening all minds, however dark, so long as they were in the light-flooded region around it.

"Have I made the meaning clear?" he asked.

He hoped she would reply that he had not, though this would have indicated a partial defeat in the object he had—to put the complex thing so plainly that no one could fail to understand. But she answered, "Yes."

He congratulated himself that his overestimate of her ignorance of affairs had not lured him into giving her the names of the parties at interest to transcribe. But did she really understand? To test her, he said:

"What do you think of it?"

"That it's wicked," replied she, without hesitation and in her small, quiet voice.

He laughed. In a way this girl, sitting there—this inconsequential and negligible atom—typefied the masses of mankind against whom that secret agreement was directed. They, the feeble and powerless ones, with their necks ever bent under the yoke of the mighty and their feet ever stumbling into the traps of the crafty—they, too, would utter an impotent "Wicked!" if they knew. His voice had the note of gentle raillery in it as he said:

"No—not wicked. Just business."

She was looking down at her book, her face expressionless. A few moments before he would have said it was an empty face. Now it seemed to him sphynxlike.

"Just business," he repeated. "It is going to take money from those who don't know how to keep or to spend it and give it to those who do know how. The money will go for building up civilization, instead of for beer and for bargain-trough finery to make working men's wives and daughters look cheap and nasty."

She was silent.

"Now, do you understand?"

"I understand what you said." She looked at him as she spoke. He wondered how he could have fancied those lack-luster eyes beautiful or capable of expression.

"You don't believe it?" he asked.

"No," said she. And suddenly in those eyes, gazing now into space, there came the unutterably melancholy look—heavy-lidded from heartache, weary-wise from long, long and bitter, experiences. Yet she still looked young—girlishly young—but it was the youthful look the classic Greek sculptors tried to give their young goddesses—the youth without beginning or end—younger than a baby's, older than the oldest of the sons of men. He mocked himself for the fancies this queer creature inspired in him; but she none the less made him uneasy.

"You don't believe it?" he repeated.

"No," she answered again. "My father has taught me—some things."

He drummed impatiently on the table. He resented her impertinence—for, like all men of clear and positive mind, he regarded contradiction as in one aspect impudent, in another aspect evidence of the folly of his contradictor. Then he gave a short laugh—the confessing laugh of the clever man who has tried to believe his own sophistries and has failed. "Well—neither do I believe it," said he. "Now, to get the thing typewritten."

She seated herself at the machine and set to work. As his mind was full of the agreement he could not concentrate on anything else. From time to time he glanced at her. Then he gave up trying to work and sat furtively observing her. What a quaint little mystery it was! There was in it—that is, in her—not the least charm for him. But, in all his experience with women, he could recall no woman with a comparable development of this curious quality of multiple personalities, showing and vanishing in swift succession.

There had been a time when woman had interested him as a puzzle to be worked out, a maze to be explored, a temple to be penetrated—until one reached the place where the priests manipulated the machinery for the wonders and miracles to fool the devotees into awe. Some men never get to this stage, never realize that their own passions, working upon the universal human love of the mysterious, are wholly responsible for the cult of woman the sphynx and the sibyl. But Norman, beloved of women, had been let by them into their ultimate secret—the simple humanness of woman; the clap-trappery of the oracles, miracles, and wonders. He had discovered that her "divine intuitions" were mere shrewd guesses, where they had any meaning at all; that her eloquent silences were screens for ignorance or boredom—and so on through the list of legends that prop the feminist cult.

But this girl—this Miss Hallowell—here was a tangible mystery—a mystery of physics, of chemistry. He sat watching her—watching the changes as she bent to her work, or relaxed, or puzzled over the meaning of one of her own hesitating stenographic hieroglyphics—watched her as the waning light of the afternoon varied its intensity upon her skin. Why, her very hair partook of this magical quality and altered its tint, its degree of vitality even, in harmony with the other changes. . . . What was the explanation? By means of what rare mechanism did her nerve force ebb and flow from moment to moment, bringing about these fascinating surface changes in her body? Could anything, even any skin, be better made than that superb skin of hers—that master work of delicacy and strength, of smoothness and color? How had it been possible for him to fail to notice it, when he was always looking for signs of a good skin down town—and up town, too—in these days of the ravages of pastry and candy? . . . What long graceful fingers she had—yet what small hands! Certainly here was a peculiarity that persisted. No—absurd though it seemed, no! One way he looked at those hands, they were broad and strong, another way narrow and gracefully weak.

He said to himself: "The man who gets that girl will have Solomon's wives rolled into one. A harem at the price of a wife—or a—" He left the thought unfinished. It seemed an insult to this helpless little creature, the more rather than the less cowardly for being unspoken; for, no doubt her ideas of propriety were firmly conventional.

"About done?" he asked impatiently.

She glanced up. "In a moment. I'm sorry to be so slow."

"You're not," he assured her truthfully. "It's my impatience. Let me see the pages you've finished."

With them he was able to concentrate his mind. When she laid the last page beside his arm he was absorbed, did not look at her, did not think of her. "Take the machine away," said he abruptly.

He was leaving for the day when he remembered her again. He sent for her. "I forgot to thank you. It was good work. You will do well. All you need is practice—and confidence. Especially confidence." He looked at her. She seemed frail—touchingly frail. "You are not strong?"

She smiled, and in an instant the frailty seemed to have been mere delicacy of build—the delicacy that goes with the strength of steel wires, or rather of the spider's weaving thread which sustains weights and shocks out of all proportion to its appearance. "I've never been ill in my life," said she. "Not a day."

Again, because she was standing before him in full view, he noted the peculiar construction of her frame—the beautiful lines of length so dextrously combined that her figure as a whole was not tall. He said, "A working woman—or man—needs health above all. Thank you again." And he nodded a somewhat curt dismissal. When she glided away and he was alone behind the closed door, he reflected for a moment upon the extraordinary amount of thinking—and the extraordinary kind of thinking—into which this poor little typewriter girl had beguiled him. He soon found the explanation for this vagary into a realm so foreign to a man of his high tastes and ambitions. "It's because I'm so in love with Josephine," he decided. "I've fallen into the sentimental state of all lovers. The whole sex becomes novel and interesting and worth while."

As he left the office, unusually late, he saw her still at work—no doubt doing over again some bungled piece of copying. She had her normal and natural look and air—the atomic little typewriter, unattractive and uninteresting. With another smile for his romantic imaginings, he forgot her. But when he reached the street he remembered her again. The threatened blizzard had changed into a heavy rain. The swift and sudden currents of air, that have made of New York a cave of the winds since the coming of the skyscrapers, were darting round corners, turning umbrellas inside out, tossing women's skirts about their heads, reducing all who were abroad to the same level of drenched and sullen wretchedness. Norman's limousine was waiting at the curb. He, pausing in the doorway, glanced up and down the street, had an impulse to return and take the girl home. Then he smiled satirically at himself. Her lot condemned her to be out in all weathers. It would not be a kindness but an exhibition of smug vanity to shelter her this one night; also, there was the question of her reputation—and the possibility of turning her head, perhaps just enough to cause her ruin. He sprang across the wind-swept, rain-swept sidewalk and into the limousine whose door was being held open by an obsequious attendant. "Home," he said, and the door slammed.

Usually these journeys between office and home or club in the evening gave Norman a chance for ten or fifteen minutes of sleep. He had discovered that this brief dropping of the thread of consciousness gave him a wonderful fresh grip upon the day, enabled him to work or play until late into the night without fatigue. But that evening his mind was wide awake. Nor could he fix it upon business. It would interest itself only in the hurrying throngs of foot passengers and the ideas they suggested: Here am I—so ran his thoughts—here am I, tucked away comfortably while all those poor creatures have to plod along in the storm. I could afford to be sick. They can't. And what have I done to deserve this good fortune? Nothing. Worse than nothing. If I had made my career along the lines of what is honest and right and beneficial to my fellow men, I'd probably be plugging home under an umbrella—and to a pretty poor excuse for a home. But I was too wise to do that. I've spent this day, as I spend all my days, in helping the powerful rich to add to their wealth and power, to add to the burdens those poor devils out there in the rain must bear. And I'm rewarded with a limousine, and all the rest of it.

These thoughts neither came from nor produced a mood of penitence, or of regret even. Norman was simply indulging in his favorite pastime—following without prejudice the leading of a chain of pure logic. He despised self-deceivers. He always kept himself free from prejudice and all its wiles. He took life as he found it; but he did not excuse it and himself with the familiar hypocrisies that make the comfortable classes preen themselves on being the guardians and saviours of the ignorant, incapable masses. When old Lockyer said one day that this was the function of the "upper classes," Norman retorted: "Perhaps. But, if so, how do they perform it? Like the brutal old-fashioned farm family that takes care of its insane member by keeping him chained in filth in the cellar." And once at the Federal Club—By the way, Norman had joined it, had compelled it to receive him just to show his associates how a strong man could break even such a firmly established tradition as that no one who amounted to anything could be elected to a fashionable club in New York. Once at the Federal Club old Galloway quoted with approval some essayist's remark that every clever human being was looking after and holding above the waves at least fifteen of his weaker fellows. Norman smiled satirically round at the complacently nodding circle of gray heads and white heads. "My observation has been," said he, "that every clever chap is shrewd enough to compel at least fifteen of his fellows to wait on him, to take care of him—do his chores—and his dirty work." The nodding stopped. Scowls appeared, except on the face of old Galloway. He grinned. He was one of the few examples of a very rich man with a sense of humor. Norman always thought it was this slight incident that led to his getting the extremely profitable—and shady—Galloway business.

No, Norman's mood, as he watched the miserable crowds afoot and reflected upon them, was neither remorseful nor triumphant. He simply noted an interesting fact—a commonplace fact—of the methods of that sardonic practical joker, Life. Because the scheme of things was unjust and stupid, because others, most others, were uncomfortable or worse—why should he make himself uncomfortable? It would be an absurdity to get out of his limousine and trudge along in the wet and the wind. It would be equally absurd to sit in his limousine and be unhappy about the misery of the world. "I didn't create it, and I can't recreate it. And if I'm helping to make it worse, I'm also hastening the time when it'll be better. The Great Ass must have brains and spirit kicked and cudgeled into it."

At his house in Madison Avenue, just at the crest of Murray Hill, there was an awning from front door to curb and a carpet beneath it. He passed, dry and comfortable, up the steps. A footman in quiet rich livery was waiting to receive him. From rising until bedtime, up town and down town, wherever he went and whatever he was about, every possible menial detail of his life was done for him. He had nothing to do but think about his own work and keep himself in health. Rarely did he have even to open or to close a door. He used a pen only in signing his name or marking a passage in a law book for some secretary to make a typewritten copy.

Upon most human beings this sort of luxury, carried beyond the ordinary and familiar uses of menial service, has a speedily enervating effect. Thinking being the most onerous of all, they have it done, also. They sink into silliness and moral and mental sloth. They pass the time at foolish purposeless games indoors and out; or they wander aimlessly about the earth chattering with similar mental decrepits, much like monkeys adrift in the boughs of a tropical forest. But Norman had the tenacity and strength to concentrate upon achievement all the powers emancipated by the use of menials wherever menials could be used. He employed to advantage the time saved in putting in shirt buttons and lacing shoes and carrying books to and from shelves. In this lay one of the important secrets of his success. "Never do for yourself what you can get some one else to do for you as well. Save yourself for the things only you can do."

In his household there were three persons, and sixteen servants to wait upon them. His sister—she and her husband, Clayton Fitzhugh, were the other two persons—his sister was always complaining that there were not enough servants, and Frederick, the most indulgent of brothers, was always letting her add to the number. It seemed to him that the more help there was, the less smoothly the household ran. But that did not concern him; his mind was saved for more important matters. There was no reason why it should concern him; could he not compel the dollars to flood in faster than she could bail them out?

This brother and sister had come to New York fifteen years before, when he was twenty-two and she nineteen. They were from Albany, where their family had possessed some wealth and much social position for many generations. There was the usual "queer streak" in the Norman family—an intermittent but fixed habit of some one of them making a "low marriage." One view of this aberration might have been that there was in the Norman blood a tenacious instinct of sturdy and self-respecting independence that caused a Norman occasionally to do as he pleased instead of as he conventionally ought. Each time the thing occurred there was a mighty and horrified hubbub throughout the connection. But in the broad, as the custom is, the Normans were complacent about the "queer streak." They thought it kept the family from rotting out and running to seed. "Nothing like an occasional infusion of common blood," Aunt Ursula Van Bruyten (born Norman) used to say. For her Norman's sister was named.

Norman's father had developed the "queer streak." Their mother was the daughter of a small farmer and, when she met their father, was chambermaid in a Troy hotel, Troy then being a largish village. As soon as she found herself married and in a position with whose duties she was unfamiliar, she set about fitting herself for them with the same diligence and thoroughness which she had shown in learning chamber work in a village hotel. She educated herself, selected not without shrewdness and carefully put on an assortment of genteel airs, finally contrived to make a most creditable appearance—was more aristocratic in tastes and in talk than the high mightiest of her relatives by marriage. But her son Fred was a Pinkey in character. In boyhood he was noted for his rough and low associates. His bosom friends were the son of a Jewish junk dealer, the son of a colored wash-woman, and the son of an Irish day laborer. Also, the commonness persisted as he grew up. Instead of seeking aristocratic ease, he aspired to a career. He had choice of several rich and well-born girls; but he developed a strong distaste for marriage of any sort and especially for a rich marriage. A fortune he was resolved to have, but it should be one that belonged to him. When he was about ready to enter a law office, his father and mother died leaving less than ten thousand dollars in all for his sister and himself. His sister hesitated, half inclined to marry a stupid second cousin who had thirty thousand a year.

"Don't do it, Ursula," Fred advised. "If you must sell out, sell for something worth while." He laughed in his frank, ironical way. "Fact is, we've both made up our minds to sell. Let's go to the best market—New York. If you don't like it, you can come back and marry that fat-wit any time you please."

Ursula inspected herself in the glass, saw a face and form exceeding fair to look upon; she decided to take her brother's advice. At twenty she threw over a multi-millionaire and married Clayton Fitzhugh for love—Clayton with only seventeen thousand a year. Of course, from the standpoint of fashionable ambition, seventeen thousand a year in New York is but one remove from tenement house poverty. As Clayton had no more ability at making money than had Ursula herself, there was nothing to do but live with Norman and "take care of him." But for this self-sacrifice of sisterly affection Norman would have been rich at thirty-seven. As he had to make her rich as well as himself, progress toward luxurious independence was slower—and there was the house, costing nearly fifty thousand a year to keep up.

There had been a time in Norman's career—a brief and very early time—when, with the maternal peasant blood hot in his veins, he had entertained the quixotic idea of going into politics on the poor or people's side and fighting for glory only. The pressure of expensive living had soon driven this notion clean off. Norman had almost forgotten that he ever had it, was no longer aware how strong it had been in the last year at law school. Young men of high intelligence and ardent temperament always pass through this period. With some—a few—its glory lingers long after the fire has flickered out before the cool, steady breath of worldliness.

All this time Norman has been dressing for dinner. He now leaves the third floor and descends toward the library, as it still lacks twenty minutes of the dinner hour.

As he walked along the hall of the second floor a woman's voice called to him, "That you, Fred?"

He turned in at his sister's sitting room. She was standing at a table smoking a cigarette. Her tall, slim figure looked even taller and slimmer in the tight-fitting black satin evening dress. Her features faintly suggested her relationship to Norman. She was a handsome woman, with a voluptuous discontented mouth.

"What are you worried about, sis?" inquired he.

"How did you know I was worried?" returned she.

"You always are."

"Oh!"

"But you're unusually worried to-night."

"How did you know that?"

"You never smoke just before dinner unless your nerves are ragged. . . . What is it?"

"Money."

"Of course. No one in New York worries about anything else."

"But this is serious," protested she. "I've been thinking—about your marriage—and what'll become of Clayton and me?" She halted, red with embarrassment.

Norman lit a cigarette himself. "I ought to have explained," said he. "But I assumed you'd understand."

"Fred, you know Clayton can't make anything. And when you marry—why—what will become of us!"

"I've been taking care of Clayton's money—and of yours. I'll continue to do it. I think you'll find you're not so badly of. You see, my position enables me to compel a lot of the financiers to let me in on the ground floor—and to warn me in good time before the house falls. You'll not miss me, Ursula."

She showed her gratitude in her eyes, in a slight quiver of the lips, in an unsteadiness of tone as she said, "You're the real thing, Freddie."

"You can go right on as you are now. Only—" He was looking at her with meaning directness.

She moved uneasily, refused to meet his gaze. "Well?" she said, with a suggestion of defiance.

"It's all very natural to get tired of Clayton," said her brother. "I knew you would when you married him. But—Sis, I mind my own business. Still—Why make a fool of yourself?"

"You don't understand," she exclaimed passionately. And the light in her eyes, the color in her cheeks, restored to her for the moment the beauty of her youth that was almost gone.

"Understand what?" inquired he in a tone of gentle mockery.

"Love. You are all ambition—all self control. You can be affectionate—God knows, you have been to me, Fred. But love you know nothing about—nothing."

His was the smile a man gives when in earnest and wishing to be thought jesting—or when in jest and wishing to be thought in earnest.

"You mean Josephine? Oh, yes, I suppose you do care for her in a way—in a nice, conventional way. She is a fine handsome piece—just the sort to fill the position of wife to a man like you. She's sweet and charming, she appreciates, she flatters you. I'm sure she loves you as much as a girl knows how to love. But it's all so conventional, so proper. Your position—her money. You two are of the regulation type even in that you're suited to each other in height and figure. Everybody'll say, 'What a fine couple—so well matched!'"

"Maybe you don't understand," said Norman.

"If Josephine were poor and low-born—weren't one of us—and all that—would you have her?"

"I'm sure I don't know," was his prompt and amused answer. "I can only say that I know what I want, she being what she is."

Ursula shook her head. "I have only to see you and her together to know that you at least don't understand love."

"It might be well if you didn't," said Norman dryly. "You might be less unhappy—and Clayton less uneasy."

"Ah, but I can't help myself. Don't you see it in me, Fred? I'm not a fool. Yet see what a fool I act."

"Spoiled child—that's all. No self-control."

"You despise everyone who isn't as strong as you." She looked at him intently. "I wonder if you are as self-controlled as you imagine. Sometimes I wish you'd get a lesson. Then you'd be more sympathetic. But it isn't likely you will—not through a woman. Oh, they're such pitifully easy game for a man like you. But then men are the same way with you—quite as easy. You get anything you want. . . . You're really going to stick to Josephine?"

He nodded. "It's time for me to settle down."

"Yes—I think it is," she went on thoughtfully. "I can hardly believe you're to marry. Of course, she's the grand prize. Still—I never imagined you'd come in and surrender. I guess you do care for her."

"Why else should I marry?" argued he. "She's got nothing I need—except herself, Ursula."

"What is it you see in her?"

"What you see—what everyone sees," replied Fred, with quiet, convincing enthusiasm. "What no one could help seeing. As you say, she's the grand prize."

"Yes, she is sweet and handsome—and intelligent—very superior, without making others feel that they're outclassed. Still—there's something lacking—not in her perhaps, but in you. You have it for her—she's crazy about you. But she hasn't it for you."

"What?"

"I can't tell you. It isn't a thing that can be put into words."

"Then it doesn't exist."

"Oh, yes it does," cried Ursula. "If the engagement were to be broken—or if anything were to happen to her—why, you'd get over it—would go on as if nothing had happened. If she didn't fit in with your plans and ambitions, she'd be sacrificed so quick she'd not know what had taken off her head. But if you felt what I mean—then you'd give up everything—do the wildest, craziest things."

"What nonsense!" scoffed Norman. "I can imagine myself making a fool of myself about a woman as easily as about anything else. But I can't imagine myself playing the fool for anything whatsoever."

There was mysterious fire in Ursula's absent eyes. "You remember me as a girl—how mercenary I was—how near I came to marrying Cousin Jake?"

"I saved you from that."

"Yes—and for what? I fell in love."

"And out again."

"I was deceived in Clayton—deceived myself—naturally. How is a woman to know, without experience?"

"Oh, I'm not criticising," said the brother.

"Besides, a love marriage that fails is different from a mercenary marriage that fails."

"Very—very," agreed he. "Just the difference between an honorable and a dishonorable bankruptcy."

"Anyhow—it's bankrupt—my marriage. But I've learned what love is—that there is such a thing—and that it's valuable. Yes, Fred, I've got the taste for that wine—the habit of it. Could I go back to water or milk?"

"Spoiled baby—that's the whole story. If you had a nursery full of children—or did the heavy housework—you'd never think of these foolish moonshiny things."

"Yet you say you love!"

"Clayton is as good as any you're likely to run across—is better than some I've seen about."

"How can you say?" cried she. "It's for me to judge."

"If you would only judge!"

Ursula sighed. "It's useless to talk to you. Let's go down."

Norman, following her from the room, stopped her in the doorway to give her a brotherly hug and kiss. "You won't make an out-and-out idiot of yourself, will you, Ursula?" he said, in his winning manner.

The expression of her eyes as she looked at him showed how strong was his influence over her. "You know I'll come to you for advice before I do anything final," said she. "Oh, I don't know what I want! I only know what I don't want. I wish I were well balanced—as you are, Fred."

The brother and sister dined alone. Clayton was, finding his club a more comfortable place than his home, in those days of his wife's disillusionment and hesitation about the future. Many weak creatures are curiously armed for the unequal conflict of existence—some with fleetness of foot, some with a pole-cat weapon of malignance, some with porcupine quills, some with a 'possumlike instinct for "playing dead." Of these last was Fitzhugh. He knew when to be silent, when to keep out of the way, when to "sit tight" and wait. His wife had discovered that he was a fool—that he perhaps owed more to his tailor than to any other single factor for the success of his splendid pose of the thorough gentleman. Yet she did not realize what an utter fool he was, so clever had he been in the use of the art of discreet silence. Norman suspected him, but could not believe a human being capable of such fathomless vacuity as he found whenever he tried to explore his brother-in-law's brain.

After dinner Norman took Ursula to the opera, to join the Seldins, and after the first act went to Josephine, who had come with only a deaf old aunt. Josephine loved music, and to hear an opera from a box one must be alone. Norman entered as the lights went up. It always gave him a feeling of dilation, this spectacle of material splendor—the women, whose part it is throughout civilization to-day to wear for public admiration and envy the evidences of the prowess of the males to whom they belong. A truer version of Dr. Holmes's aphorism would be that it takes several generations in oil to make a deep-dyed snob—wholly to destroy a man's or a woman's point of view, sense of the kinship of all flesh, and to make him or her over into the genuine believer in caste and worshiper of it. For all his keenness of mind, of humor, Norman had the fast-dyed snobbishness of his family and friends. He knew that caste was silly, that such displays as this vulgar flaunting of jewels and costly dresses were in atrocious bad taste. But it is one thing to know, another thing to feel; and his feeling was delight in the spectacle, pride in his own high rank in the aristocracy.

His eyes rested with radiant pleasure on the girl he was to marry. And she was indeed a person to appeal to the passion of pride. Simply and most expensively dressed in pearl satin, with only a little jewelry, she sat in the front of her parterre box, a queen by right of her father's wealth, her family's position, her own beauty. She was a large woman—tall, a big frame but not ungainly. She had brilliant dark eyes, a small proud head set upon shoulders that were slenderly young now and, even when they should became matronly, would still be beautiful. She had good teeth, an exquisite smile, the gentle good humor of those who, comfortable themselves, would not have the slightest objection to all others being equally so. Because she laughed appreciatively and repeated amusingly she had great reputation for wit. Because she industriously picked up from men a plausible smatter of small talk about politics, religion, art and the like, she was renowned as clever verging on profound. And she believed herself both witty and wise—as do thousands, male and female, with far less excuse.

She had selected Norman for the same reason that he had selected her; each recognized the other as the "grand prize." Pity is not nearly so close kin to love as is the feeling that the other person satisfies to the uttermost all one's pet vanities. It would have been next door to impossible for two people so well matched not to find themselves drawn to each other and filled with sympathy and the sense of comradeship, so far as there can be comradeship where two are driving luxuriously along the way of life, with not a serious cause for worry. People without half the general fitness of these two for each other have gone through to the end, regarding themselves and regarded as the most devoted of lovers. Indeed, they were lovers. Only one of those savage tests, to which in all probability they would never be exposed, would or could reveal just how much, or how little, that vague, variable word lovers meant when applied to them.

As their eyes met, into each pair leaped the fine, exalted light of pride in possession. "This wonderful woman is mine!" his eyes said. And her eyes answered, "And you—you most wonderful of men—you are mine!" It always gave each of them a thrill like intoxication to meet, after a day's separation. All the joy of their dazzling good fortune burst upon them afresh.

"I'll venture you haven't thought of me the whole day," said she as he dropped to the chair behind her.

It was a remark she often made—to give him the opportunity to say, "I've thought of little else, I'm sorry to say—I, who have a career to look after." He made the usual answer, and they smiled happily at each other. "And you?" he said.

"Oh, I? What else has a woman to think about?"

Her statement was as true as his was false. He was indeed all she had to think about—all worth wasting the effort of thought upon. But he—though he did not realize it—had thought of her only in the incidental way in which an ambition-possessed man must force himself to think of a woman. The best of his mind was commandeered to his career. An amiable but shakily founded theory that it was "our" career enabled him to say without sense of lying that his chief thought had been she.

"How those men down town would poke fun at you," said she, "if they knew you had me with you all the time, right beside you."

This amused him. "Still, I suspect there are lots of men who'd be exposed in the same way if there were a general and complete show-down."

"Sometimes I wish I really were with you—working with you—helping you. You have girls—a girl—to be your secretary—or whatever you call it—don't you?"

"You should have seen the one I had to-day. But there's always something pathetic about every girl who has to make her own living."

"Pathetic!" protested Miss Burroughs. "Not at all. I think it's fine."

"You wouldn't say that if you had tried it."

"Indeed, I should," she declared with spirit. "You men are entirely too soft about women. You don't realize how strong they are. And, of course, women don't resist the temptation to use their sex when they see how easy it is to fool men that way. The sad thing about it is that the woman who gets along by using her sex and by appealing to the soft-heartedness of men never learns to rely on herself. She's likely to come to grief sooner or later."

"There's truth in all that," said Norman. "Enough to make it dangerously unjust. There's so much lying done about getting on that it's no wonder those who've never tried to do for themselves get a wholly false notion of the situation. It is hard—bitterly hard—for a man to get on. Most men don't. Most men? All but a mere handful. And if those who do get on were to tell the truth—the whole truth—about how they succeeded—well, it'd not make a pleasant story."

"But you've got on," retorted the girl.

"So I have. And how?" Norman smiled with humorous cynicism. "I'll never tell—not all—only the parts that sound well. And those parts are the least important. However, let's not talk about that. What I set out to say was that, while it's hard for a man to make a decent living—unless he has luck—and harder still—much harder—for him to rise to independence——"

"It wasn't so dreadfully hard for you," interrupted Josephine, looking at him with proud admiration. "But then, you had a wonderful brain."

"That wasn't what did it," replied he. "And, in spite of all my advantages—friendships, education, enough money to tide me over the beginnings—in spite of all that, I had a frightful time. Not the work. Of course, I had to work, but I like that. No, it was the—the maneuvering, let's call it—the hardening process."

"You!" she exclaimed.

"Everyone who succeeds—in active life. You don't understand the system, dear. It's a cutthroat game. It isn't at all what the successful hypocrites describe in their talks to young men!" He laughed. "If I had followed the 'guides to success,' I'd not be here. Oh, yes, I've made terrible sacrifices, but—" his look at her made her thrill with exaltation—"it was worth doing. . . . I understand and sympathize with those who scorn to succeed. But I'm glad I happened not to be born with their temperament, at least not with enough of it to keep me down."

"You're too hard on yourself, too generous to the failures."

"Oh, I don't mean the men who were too lazy to do the work or too cowardly to dare the—the unpleasant things. And I'm not hard with myself—only frank. But we were talking of the women. Poor things, what chance have they got? You scorn them for using their sex. Wait till you're drowning, dear, before you criticise another for what he does to save himself when he's sinking for the last time. I used everything I had in making my fight. If I could have got on better or quicker by the aid of my sex, I'd have used that."

"Don't say those things, Fred," cried Josephine, smiling but half in earnest.

"Why not? Aren't you glad I'm here?"

She gave him a long look of passionate love and lowered her eyes.

"At whatever cost?"

"Yes," she said in a low voice. "But I'm sure you exaggerate."

"I've done nothing you wouldn't approve of—or find excuses for. But that's because you—I—all of us in this class—and in most other classes—have been trained to false ideas—no, to perverted ideas—to a system of morality that's twisted to suit the demands of practical life. On Sundays we go to a magnificent church to hear an expensive preacher and choir, go in expensive dress and in carriages, and we never laugh at ourselves. Yet we are going in the name of One who was born in a stable and who said that we must give everything to the poor, and so on."

"But I don't see what we could do about it—" she said hesitatingly.

"We couldn't do anything. Only—don't you see my point?—the difference between theory and practice? Personally, I've no objection—no strong objection—to the practice. All I object to is the lying and faking about it, to make it seem to fit the theory. But we were talking of women—women who work."

"I've no doubt you're right," admitted she. "I suppose they aren't to blame for using their sex. I ought to be ashamed of myself, to sneer at them."

"As a matter of fact, their sex does few of them any good. The reverse. You see, an attractive woman—one who's attractive as a woman—can skirmish round and find some one to support her. But most of the working women—those who keep on at it—don't find the man. They're not attractive, not even at the start. After they've been at it a few years and lose the little bloom they ever had—why, they've got to take their chances at the game, precisely like a man. Only, they're handicapped by always hoping that they'll be able to quit and become married women. I'd like to see how men would behave if they could find or could imagine any alternative to 'root hog or die.'"

"What's the matter with you this evening, Fred? I never saw you in such a bitter mood."

"We never happened to get on this subject before."

"Oh, yes, we have. And you always have scoffed at the men who fail."

"And I still scoff at them—most of them. A lot of lazy cowards. Or else, so bent on self-indulgence—petty self-indulgence—that they refuse to make the small sacrifice to-day for the sake of the large advantage day after to-morrow. Or else so stuffed with vanity that they never see their own mistakes. However, why blame them? They were born that way, and can't change. A man who has the equipment of success and succeeds has no more right to sneer at one less lucky than you would have to laugh at a poor girl because she wasn't dressed as well as you."

"What a mood! Something must have happened."

"Perhaps," said he reflectively. "Possibly that girl set me off."

"What girl?"

"The one I told you about. The unfortunate little creature who was typewriting for me this afternoon. Not so very little, either. A curious figure she had. She was tall yet she wasn't. She seemed thin, and when you looked again, you saw that she was really only slender, and beautifully shaped throughout."

Miss Burroughs laughed. "She must have been attractive."

"Not in the least. Absolutely without charm—and so homely—no, not homely—commonplace. No, that's not right, either. She had a startling way of fading and blazing out. One moment she seemed a blank—pale, lifeless, colorless, a nobody. The next minute she became—amazingly different. Not the same thing every time, but different things."

Frederick Norman was too experienced a dealer with women deliberately to make the mistake—rather, to commit the breach of tact and courtesy—involved in praising one woman to another. But in this case it never occurred to him that he was talking to a woman of a woman. Josephine Burroughs was a lady; the other was a piece of office machinery—and a very trivial piece at that. But he saw and instantly understood the look in her eyes—the strained effort to keep the telltale upper lip from giving its prompt and irrepressible signal of inward agitation.

"I'm very much interested," said she.

"Yes, she was a curiosity," said he carelessly.

"Has she been there—long?" inquired Josephine, with a feigned indifference that did not deceive him.

"Several months, I believe. I never noticed her until a few days ago. And until to-day I had forgotten her. She's one of the kind it's difficult to remember."

He fell to glancing round the house, pretending to be unconscious of the furtive suspicion with which she was observing him. She said:

"She's your secretary now?"

"Merely a general office typewriter."

The curtain went up for the second act. Josephine fixed her attention on the stage—apparently undivided attention. But Norman felt rather than saw that she was still worrying about the "curiosity." He marveled at this outcropping of jealousy. It seemed ridiculous—it was ridiculous. He laughed to himself. If she could see the girl—the obscure, uninteresting cause of her agitation—how she would mock at herself! Then, too, there was the absurdity of thinking him capable of such a stoop. A woman of their own class—or a woman of its corresponding class, on the other side of the line—yes. No doubt she had heard things that made her uneasy, or, at least, ready to be uneasy. But this poorly dressed obscurity, with not a charm that could attract even a man of her own lowly class—It was such a good joke that he would have teased Josephine about it but for his knowledge of the world—a knowledge in whose primer it was taught that teasing is both bad taste and bad judgment. Also, it was beneath his dignity, it was offense to his vanity, to couple his name with the name of one so beneath him that even the matter of sex did not make the coupling less intolerable.

When the curtain fell several people came into the box, and he went to make a few calls round the parterre. He returned after the second act. They were again alone—the deaf old aunt did not count. At once Josephine began upon the same subject. With studied indifference—how amusing for a woman of her inexperience to try to fool a man of his experience!—she said:

"Tell me some more about that typewriter girl. Women who work always interest me."

"She wouldn't," said Norman. The subject had been driven clean out of his mind, and he didn't wish to return to it. "Some day they will venture to make judicious long cuts in Wagner's operas, and then they'll be interesting. It always amuses me, this reverence of little people for the great ones—as if a great man were always great. No—he is always great. But often it's in a dull way. And the dull parts ought to be skipped."

"I don't like the opera this evening," said she. "What you said a while ago has set me to thinking. Is that girl a lady?"

"She works," laughed he.