This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Friends in Feathers and Fur, and Other Neighbors

For Young Folks

Author: James Johonnot

Release Date: February 14, 2009 [eBook #28077]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRIENDS IN FEATHERS AND FUR, AND OTHER NEIGHBORS***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/friendsinfeather00johorich |

Good-morning! good-morning! the birdies sing;

Good-by to the windy days of spring!

The sun is so bright, that we must be gay!

Good-morning! good-morning! this glad summer day.

A machine, turned by a crank, has been made to speak words, but nothing below a human being has been able to get thought from a written or printed page and convey it to others. To make the machine requires a vast amount of labor expended upon matter; to get the thought requires the awakening of a human spirit. The work of the machine is done when the crank stops; the mental work, through internal volition, goes on to ever higher achievements.

In schools much labor has been spent in trying to produce human speaking-machines. Words are built up out of letters; short words are grouped into inane sentences such as are never used; and sentences are arranged into unnatural and insipid discourse. To grasp the thin ghost of the thought, the little human spirit must reverse its instinct to [6]reach toward the higher, and, mole-like, burrow downward.

The amount of effort spent in this way, if given to awakening thought, would much more effectively secure the mechanical ends sought, and at the same time would yield fruit in other fields of mental activity.

The matter selected for these higher and better purposes must possess a human interest. The thoughts that bear fruit are those with roots set in past experiences, but which, outgrowing these experiences, reach out toward new light.

In this little book we have again given the initial steps of science rather than the expression of scientific results. Beginning with familiar forms of life, the pupil is led to see more clearly that which is about him, and then to advance into the realm of the unknown with assured steps, in the tried paths of investigation and comparison.

While giving prominence to the facts that inform, we have not been unmindful of the fancy that stimulates. The steady flow of description is frequently interrupted by the ripple of story and verse. While we have made no effort to secure the favor of Mr. Gradgrind by looking at facts only on their lower side, we trust that our effort may prove of some service in the anxious work of parent and teacher.

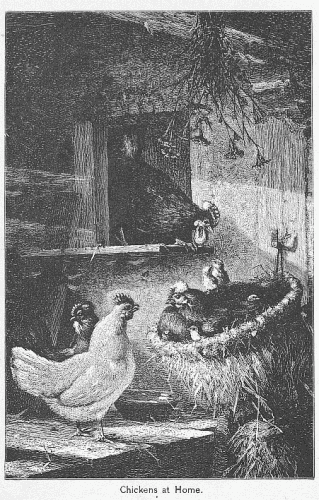

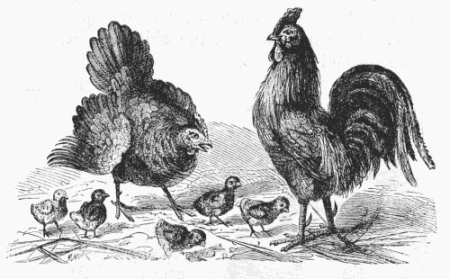

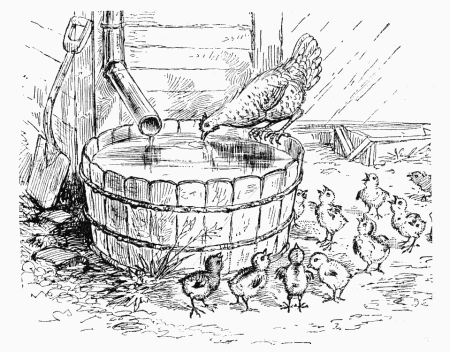

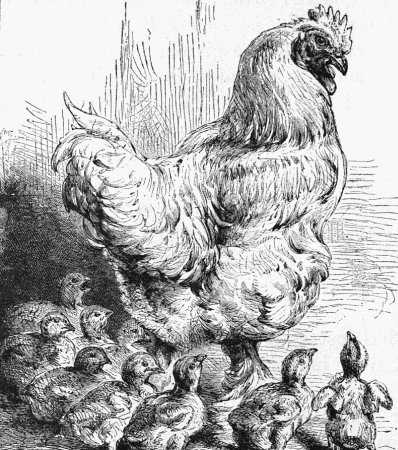

1. Here we find the hen and chickens, a new company of our farm-yard friends. We see that they are very unlike the other friends we have been studying, and, though we know them well, we may find out something new about them.

2. Instead of a coat of hair or fur, the hen is covered with feathers, all pointing backward and lying over each other, so that the rain falls off as from the shingles of a house.

3. When we studied the cat, we found that she had four legs for walking and running, and[12] that she used the paws on her front legs for scratching and catching her prey.

4. We have but two legs for walking or running, our fore legs being arms, and our paws, hands.

5. These new friends, the chickens, have but two legs, and in this way are more like boys and girls than are cats and dogs.

6. But the chicken has the same number of limbs as the others, only those in front are wings instead of fore legs or arms.

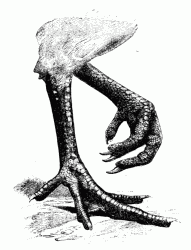

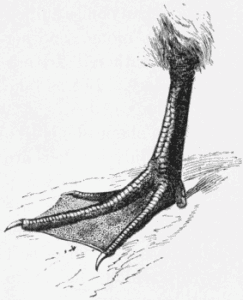

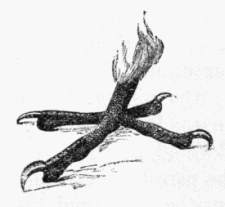

7. Here is a picture of the legs and feet of a hen. We see that the legs are covered with scales, and that each foot has four toes, three pointing forward and one back. Each toe has a long, sharp, and strong nail.

8. Let us look at the hen when she is walking slowly! As she lifts up each foot, her toes curl[13] up, very much as our fingers do when we double them up to make a fist.

9. When the chicken is about a year old, a spur, hard like horn, begins to grow on the inside of each leg. Upon the old cocks these spurs are long and sharp, and he can strike savage blows with them.

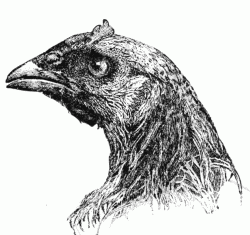

10. It is when we look a hen in the face that we see how much it differs from all the animals we have studied before.

11. The head stands up straight, and the eyes are placed on each side, so that it can look forward, to the side, and partly backward.[14]

12. Two little ears are just back and below the eyes; at first we would hardly know what they are, they are so small and unlike the other ears which we have seen.

13. All the lower part of the face is a bill, hard like horn, and running out to a point. The bill opens and makes the mouth, and two holes in the upper part make the nose.

14. As the whole bill is hard like bone, the hen does not need teeth, and does not have any. She was never known to complain with the tooth-ache.

15. Large bits of food she scratches apart with her feet, or breaks up with her bill; but, as she can not chew, the pieces she takes into her mouth she swallows whole.

16. Upon the top of the head is a red, fleshy comb, which is much larger on cocks than on hens. This comb is sometimes single, and sometimes double.

17. Under the bill on each side there hangs down a wattle of red flesh that looks very much like the comb.

18. The tail of the cock has long feathers, which curl over the rest and give him a very graceful appearance.

1. When the hen walks, she folds her wings close by her side; but when she flies, she spreads them out like a fan. Her body is so heavy that she can fly but a little ways without resting.

2. At night fowls find a place to roost upon a tree, or a piece of timber placed high on purpose for them. Their toes cling around the stick that they stand on, so that they do not fall off.

3. Fowls live upon grain, bugs, and worms.[16] With their long nails and strong toes they scratch in the earth, and with their sharp bills they pick up anything which they find good to eat.

4. If the morsel of food found is too large to be swallowed whole, they pick it to pieces with their bills. The old hen always picks the food to pieces for her chickens.

5. The hen lays eggs, usually one every day, until she has laid from fifteen to twenty. If her eggs are carried away, she will continue to lay for a longer time.

6. When she has a nest full of eggs, she sits upon them, keeping them warm with her body for three weeks. At the end of that time the eggs hatch out into little chicks.

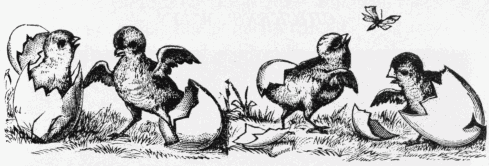

7. When the hatching time comes, the chick inside the egg picks a little hole in his shell, so that he can get his bill out, and then he breaks the shell so that he can step out.

8. When first hatched, the chickens are covered with a fine down, which stays on until their feathers grow. They are able to run about the moment they are out of the shell.

9. The hen is a careful mother. She goes about searching and scratching for food, and, when she finds it, she calls her chickens, and does not eat any herself until they are supplied.

[17]

10. At night, and whenever it is cold, she calls them together and broods them, by lifting her wings a little and letting them cuddle under her to keep warm.

11. When anything disturbs her chicks, the old hen is ready to fight, picking with her bill and striking with her wings with all her might.

12. The cock is a fine gentleman. He walks about in his best clothes, which he brushes every day and keeps clean. He struts a little, to show what a fine bird he is.

13. In the morning he crows long and loud, to let people know it is time to get up; and every little while during the day he crows, to tell the neighbors that all is well with him and his family.

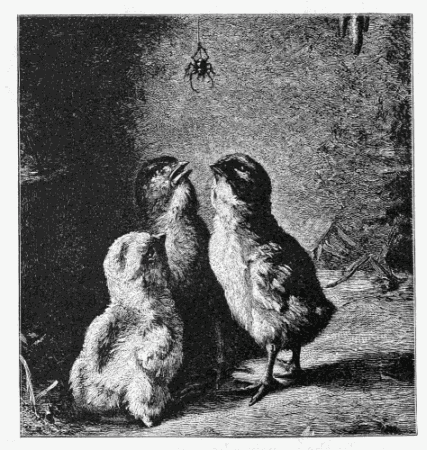

1. When first hatched, chickens look about for something to eat, and they at once snap at a fly or bug which comes in their way. Here we[19] have the picture of three little chickens reaching for a spider that hangs on its thread.

2. Then the little chick knows how to say a great many things. Before he is a week old, if we offer him a fly, he gives a little pleasant twitter, which says, "That is good!" but present to him a bee or a wasp, and a little harsh note says, "Away with it!"

3. When running about, the chick has a little calling note, which says, "Here I am!" and the old hen clucks back in answer; but, when there is danger, he calls for help in a quick, sharp voice, which brings the old hen to him at once.

4. The hen has also her ways of speech. She cackles long and loud, to let her friends know that she has just laid an egg; she clucks, to keep up a talk with her chicks; she calls them when she has found something to eat; and she softly coos over them when she broods them under her wings.

5. But, should she see a strange cat or a hawk about, she gives a shriek of alarm, which all the little ones understand, for they run and hide as quickly as possible. When the danger is past she gives a cluck, which brings them all out of their hiding-places.

1. Sometimes ducks' eggs are placed under the hen, and she hatches out a brood of young ducks. As soon as they are out of the shell they make for the water, and plunge in and have a swim.[21]

2. The old hen can not understand this. She keeps out of the water when she can. She thinks her chicks will be drowned, and she flies about in great distress until they come out.

3. At an inn in Scotland a brood of chickens was hatched out in cold weather, and they all died. The old hen at once adopted a little pig, not old enough to take care of himself, that was running about the farm-yard.

4. She would cluck for him to come when she had round something to eat, and, when he shivered with cold, she would warm him under her wings. The pig soon learned the hen's ways, and the two kept together, the best of friends, until the pig grew up, and did not need her help any more.

5. There is another story of a hen that adopted three little kittens, and kept them under her wings for a long time, not letting their mother go near them. The old cat, however, watched her chance, and carried off the kittens one by one to a place of safety.

6. Hens do not always agree, and sometimes they are badly treated by one another, as is shown in this story:

7. An old hen had been sitting on a nest full of eggs, in a quiet place in the garden, until they[22] were nearly ready to hatch. One day she left her nest a few moments to get something to eat, and, while she was gone, a bantam hen, on the watch, took possession of it.

8. When the real mother came back, she was in great distress; but the bantam kept the nest, and in a few days hatched out as many of the eggs as she could cover.

9. She then strutted about at the head of her company of chickens, and passed them off upon her feathered friends as her own.

10. Hens are usually timid, and they run or fly away when they see any danger. But in defence of their chicks they are often very bold.

11. A rat one day went into a chicken-house where there was a brood of young chickens. The old hen pounced upon him, and a fierce battle took place.

12. The rat soon had enough of it, and tried to get away; but the hen kept at him until one of the family came and killed him.

13. One day a sparrow-hawk flew down into a farm-yard to catch a chicken. A cock about a year old at once darted at him and threw him on his back.

14. While lying there he could defend himself[23] with his talons and beak; but when he rose and tried to take wing, the cock rushed at him and upset him the second time.

15. The hawk by this time thought more of getting away than he did of his dinner; but the cock kept him down until somebody came and caught him.

16. The cock looks after the hens and chicks, and is ready to fight for them in time of danger. He scratches for them, and, when he finds something good to eat, like the gentleman he is, he calls them to the feast before he touches it himself.

17. He also has his own fun. Sometimes he will find a tempting worm and call all the hens, and, just as they are about to seize it, he will swallow it, and give a sly wink, as much as to say, "Don't you wish you may get it!"

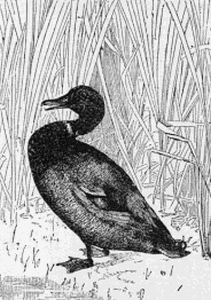

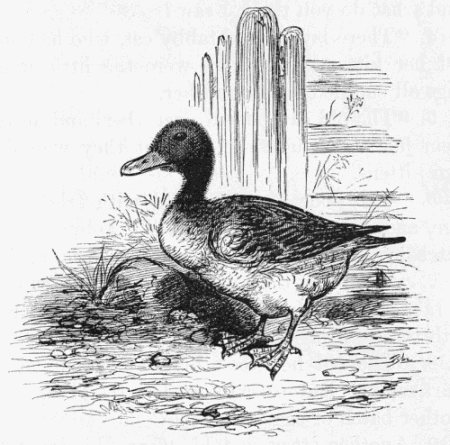

1. Here comes a duck waddling along, another of our feathered friends on two legs. Let us take a good look at her.

2. In shape she is like the hen, only her legs are shorter and her body flatter. Her feathers are very thick, and next her skin she has a coat of soft down, which helps to keep her warm.

3. The duck's wings are strong, and she can fly to a great distance without being tired. Wild ducks fly a great many miles without resting.

4. The duck has no comb or wattles on its head, and its long bill is broad and blunt at the end. Its tail is short and pointed, and it has no drooping tail feathers. The duck has the same number of toes as a chicken, but its foot is webbed by a strong skin, which binds the toes together.

5. The duck is formed for swimming. It pushes itself along in the water, using its webbed[26] feet for paddles. The down on its breast is filled with oil, so that no water can get through to the skin.

6. When in the water we will see the duck often dive, and stay under so long that we begin to fear it will never come up, and we wonder what it does that for.

7. If we could watch it under the water, we would see that it thrusts its broad bill into the mud at the bottom, and brings out worms, water-bugs, and roots of plants, which it eats.

8. Should a frog or a tadpole come within reach, the duck would snap it up in an instant; and even fish are sometimes caught.

9. The old mother duck every morning leads her brood to the water. As she waddles along on the land, her gait is very awkward, but the moment she and her little ones get to the water they sail out in the most graceful way.

1. Dame Bridson had several families of ducklings, and one day as I watched her feeding them she told me this story:

2. "I once put a number of duck's eggs under a hen, and they all hatched out nicely. When the ducks were a few days old, the hen left them for a few minutes to pick up some food.[28]

3. "When she came back I heard a furious cackling, and ran to see what was the matter. And what do you think I saw?

4. "There lay my old tabby cat, who had just lost her kittens, and there were the little ducklings all cuddled up around her.

5. "The old cat purred over them and licked them just as though she thought they were her own kittens.

6. "The poor hen was wild with fright and rage, and a little way back stood Toby, the old watch-dog, trying to find out what was the trouble.

7. "From that time, until they were big enough to take care of themselves, tabby came and slept with the ducklings every night.

8. "The old hen took her loss very much to heart, and I had to comfort her by giving her another batch of eggs to sit on."

9. Another story is told of an old dog who took a fancy to a brood of young ducks, who had lost their mother. They followed him about everywhere, and, when he lay down, the ducklings nestled all about him.

10. One duckling used to scramble upon the dog's head and sit down upon his eye; but the old dog never moved, though the pressure upon[29] the eye must have hurt him. He seemed to think more of his little friends than of himself.

11. One day a young lady was sitting in a room close by a farm-yard, in which there were chickens, ducks, and geese feeding and playing together.

12. While busy with her sewing, a drake came into the room, took hold of her dress, and tried to pull her toward the door.

13. She was afraid at first, and pushed him away; but he came back again and again, and she soon saw that he was not angry, but was trying to get her to follow him.

14. She got up, and he led her to the side of a pond, where she found a duck with its head caught in a railing. She made haste to set the poor creature free, and the drake flapped his wings and gave a joyous quack of thanks.

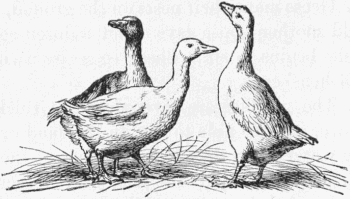

1. The goose and the duck are much alike in looks and ways. The legs of the goose are longer, so that it stands higher and can walk better on land.

2. The goose is larger than the duck, its neck longer, and its wings broader. Its feet are webbed, so that it can swim well in the water.

3. Its bill is broad and more pointed than that of a duck. Its wings are very strong, and it is able to fly a great distance without rest.

4. When in the water it does not dive like the duck, but it thrusts its bill down into the water or mud the length of its long neck.

5. The feathers of the goose are white or gray, and very light and soft, and are used for making beds and pillows. Not a great while ago pens were made of the quills that come out of the[31] wings of the goose, and everybody who wrote used them.

6. Geese make their nests on the ground, where the old mother goose lays about a dozen eggs before she begins to sit. These eggs are twice the size of hens' eggs.

7. The goslings are covered with a thick coat of down, and are able to run on the land or swim in the water when they first come out of the shell.

8. The goose and the gander together take good care of their goslings. When anything comes near, they stretch out their necks and give a loud hiss.

9. Should a strange dog venture too near, they will take hold of him with their bills and beat him with their wings until he is glad to get away.

1. The feathers of the goose are of great value. They are plucked out three or four times a year, at times when the weather is warm and fair.

2. The goose likes cold water. Great flocks of wild geese live in the swamps and lakes in the cold northern regions, and we can see them flying overhead in the spring and fall.

3. A miller once had a flock of geese, and he lost them all except one old goose, that for a long time swam round alone on the mill-pond.

4. Now, the miller's wife placed a number of duck's eggs under a hen, and, as soon as they were hatched, the ducklings ran to the water.

5. The old goose, seeing the fright and flurry of the hen, sailed up with a noisy gabble, and took[33] the ducklings in charge, and swam about with them.

6. When they were tired, she led them to the shore and gave them back to the care of the hen, who, to her great joy, found that they were all safe and sound.

7. The next day down came the ducklings to the pond, with the hen fussing and fretting as before. The goose was waiting near the shore.

8. When the ducklings had taken to the water, the hen, to get near them, flew upon the back of the goose, and the two sailed up and down the pond after the ducklings.

9. So, day after day, away sailed the ducklings, and close behind them came the mother hen, now quite at her ease on the back of the friendly goose, watching her gay little brood.

10. A lady tells this story of a gander: "My grandfather was fond of pets, and he had once a droll one, named Swanny. This was a gander he had raised near the house, because he had been left alone by the other geese.

11. "This gander would follow him about like a dog, and would be very angry if anyone laid a hand upon him.

12. "Swanny sometimes tried to make himself[34] at home with the flock of geese; but they always drove him away, and then he would run and lay his head on my grandfather's knee, as though sure of finding comfort there.

13. "At last he found a friend of his own kind. An old gray goose became blind, and the flock turned her out. Swanny took pity on her, led her about, and provided for her all the food she needed.

14. "When he thought she needed a swim, he took her neck in his bill and led her to the water, and then guided her about by arching his neck over hers.

15. "When she hatched out a brood of goslings, Swanny took the best of care of them, as well as of their mother. In this way they lived together for several years."

16. Here is another story, showing that geese have good sense:

17. A flock of geese, living by a river, built their nests on the banks; but the water-rats came and stole the eggs.

18. Then the geese made their nests in the trees, where the rats could not get at them; and when the goslings were hatched, they brought them down one by one under their wings.

1. To show that the goose has a great deal of good sense, this story is told:

2. At a small country church a poor blind woman used to come in every Sunday morning, as regular as the clock, a minute or two behind the pastor.

3. She was always alone, came in the last and went away the first of any. The pastor, who was a new-comer, was puzzled to know how she got about so well.

4. One day he set out to visit her, and found that she lived in a small cottage, more than a mile away.

5. On his way to her home, he crossed a stream on a narrow rustic bridge, with a railing on only one side.

6. He rapped at the door, and asked of the[36] woman who opened it, "Does the blind woman who comes to church every Sunday live here?" "Yes, that she does! but she's out in the field now."

7. "Why do you let the poor creature come all the way by herself, and across the bridge, too? She will fall into the water some day and be drowned!"

8. The woman laughed softly. "Sure, she doesn't go alone—the goose takes her!" said she.

9. "What do you mean by the goose taking her?" said the pastor.

10. "Sure," said the woman, "it is the goose whose life she saved when it was a little gosling. And now it comes every Sunday at the same minute to take her to church.

11. "It gets her skirt into its mouth, and leads her along quite safely. When it comes to the bridge it puts her next the rail, and keeps between her and the water.

12. "It stays about the church-door till the service is out, and then it takes her by the gown and brings her home just the same."

13. The pastor was greatly pleased with this story, and soon after he preached a sermon on kindness to animals.

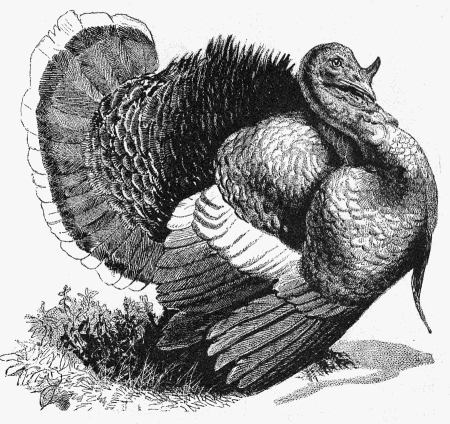

1. The turkey is about as large as a goose, but its legs are longer, and it stands up higher. Its feet are partly webbed, so that it can swim a little.

2. Its bill is short, thick, and pointed, and upon its head, above and between the eyes, grows a fleshy wattle, which does not stand up like the[38] comb of a cock, but hangs down over the bill. Upon the breast is a tuft of long, coarse hair.

3. The tail is broad and rounded, and hangs downward; but the turkey can raise it and spread it out like a fan.

4. The turkey can fly but a little way, but it can run very fast. At night, it roosts on trees or high places.

5. The hen-turkey is timid, but the old gobbler rather likes to quarrel. He is a vain bird, and it is funny to see him strut up and down, with his tail spread out, and his wings drawn down, his feathers ruffled, and his neck drawn back, and to hear him puff, and cry, "Gobble! gobble!"

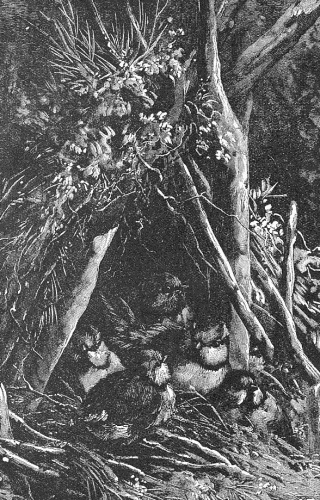

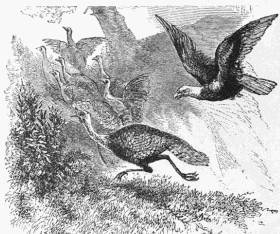

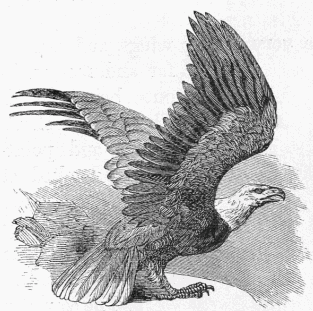

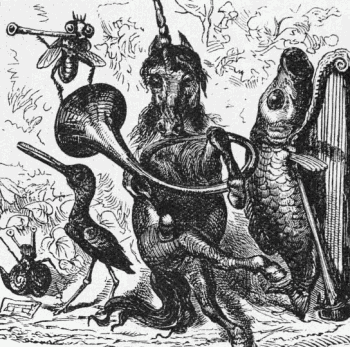

6. Great flocks of wild turkeys are found in the West, where they live in the woods upon nuts and insects. The eagles sometimes pounce down and carry off young turkeys, as is shown in this picture.

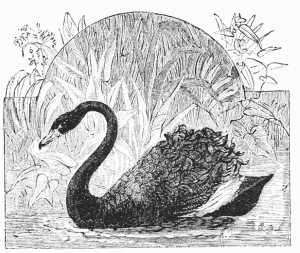

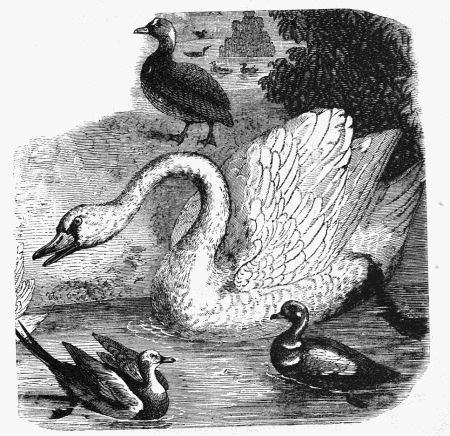

1. Here we have the picture of the swan, the largest bird of the goose kind. It is not often seen in this country, but is found in the Central Park, New York, and in a few other places.

2. It has short, stout legs, and webbed feet,[40] like the duck, and it waddles along on the land in a slow and awkward way. It is clothed with feathers of a fine quality, like the goose, and those we see in this country are pure white. Black swans are found in some countries.

3. Its neck is much longer than that of the goose, and when it swims, sitting high in the water, with its long neck arched, it is one of the most graceful birds in the world. It has strong wings, and wild swans can fly a long distance without tiring. Tame swans do not fly far.

4. The bill of the swan is broad, and pointed like that of the goose, but a little longer. Below the eyes, and at the base of the bill, a narrow band of black extends across the front of the head.

5. The swans run in pairs. The mother swan lays from five to eight eggs, and hatches them in six weeks. The young swans are called cygnets. They are covered with down, and are able to walk and swim when first out of the shell.

6. The father swan watches the nest, and helps take care of the young ones. He will fly at anything that comes near, and he is able to strike terrible blows with his wings. He can drive away any bird, even the eagle.

7. Swans usually build nests of a few coarse[41] sticks, and a lining of grass or straw. They have a curious habit, however, of raising their nests higher, and of raising the eggs at the same time.

8. At times they seem to know that some danger threatens them, and then they turn their instinct for raising their nests to some purpose. A person who observed all the facts tells this story:

9. For many years an old swan had built her nest on the border of a park, by the river-side. From time to time she had raised her nest, but never more than a few inches.

10. Once, when there had been no rain for a long time, and the river was very low, she began to gather sticks and grasses to raise her nest, and she would scarcely stop long enough to eat.

11. She seemed so anxious to get materials for nest-building that she attracted the attention of the family living near by, and a load of straw was carried to her. This she worked all into her nest, and never stopped until the eggs had been raised two and a half feet.

12. In the night a heavy rain fell, the river flowed over its banks, and the water came over the spot where the eggs had been; but it did not quite come up to the top of the new nest, and so the swan saved them.

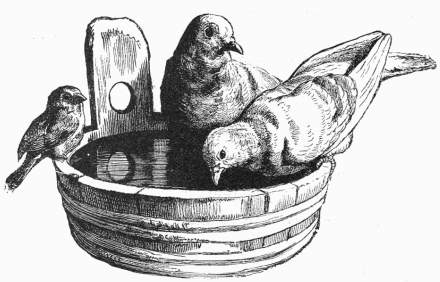

1. Everybody likes the dove; it is such a pretty bird, and is always so clean. It flies all about the yard, the garden, and the street. Even the rudest boys do not often disturb it.

2. It is about the size of a half-grown chicken, and looks more like a chicken than any of the other birds we have studied.

3. The doves about our houses are usually white, or a bluish gray. They live in pairs, each pair having its own nest, or home; but where[43] doves are kept, many pairs live in the same house or dove-cote.

4. They have a short, pointed bill, like a chicken, and strong legs and toes, so that they can walk and scratch easily.

5. The mother dove lays but two eggs before sitting, and then her mate sits on the nest half of the time until the eggs are hatched. The young doves, called squabs, are covered with down like chickens, but, unlike chickens, the old ones must feed them a week or two before they are able to go about by themselves.

6. Both the father and mother dove feed the young ones with a kind of milky curd which comes from their own crops.

7. When the chicken drinks, it sips its bill full,[44] and then raises its head and swallows; but the dove does not raise its head until it has drank enough.

8. The pigeon—which is another name for the dove—has very strong wings, and can fly far and fast without tiring. When taken from their home a great distance, pigeons will fly straight back.

9. Before we had railroads and telegraphs, people would take pigeons away from home, and send them back with a letter tied under their wings. These were called carrier-pigeons.

10. The doves in each home are very fond of each other. We can hear the father dove softly cooing to his mate at almost any time when they are about.

11. One day a farmer shot a male dove, and tied the body to a stake to scare away other birds. The poor widow was in great distress. She first tried to call him away, and then she brought him food. When she saw he did not eat, her cries were pitiable.

12. She would not leave the body, but day after day she continued to walk about the stake, until she had worn a beaten track around it. The farmer's wife took pity on her, and took away the dead bird, and then she went back to the dove-cote.

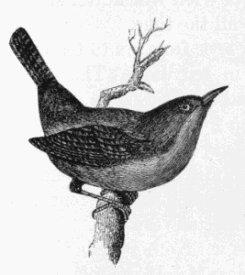

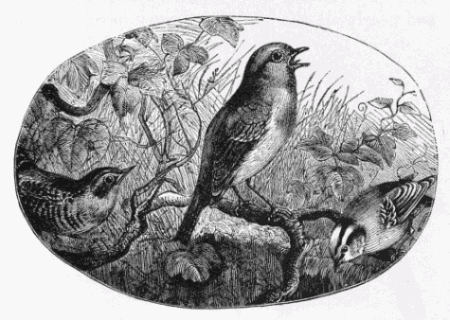

1. One of the prettiest birds that fly about our doors in summer is the friendly little wren. It makes its home near the house, and its glad song can be heard throughout the whole day.

2. One kind of wren builds its nest under the eaves, as shown in the picture; but the common house-wren builds in almost any hole it can find in a shed or stable.

3. They have been known to choose an old boot left standing in a corner, an old hat hanging against the wall, and one time a workman, taking down a coat which he had left for two or three days, found a wren's nest in the sleeve.

4. The wren flies low, and but a little way at a time. Its legs, like most of the singing birds, are small and weak, and it does not walk, but when on the ground it goes forward by little hops.

5. It flies with a little tremor of its wings, but[48] without any motion of its body or tail. While its mate is sitting, the father wren will flutter slowly through the air, singing all the time.

6. The mother wren lays from six to ten eggs, and hatches them out in ten days. The young birds are naked of feathers, and seem to have only mouths, which open for something to eat.

7. The old birds are busy in bringing the young ones worms and insects, until they are old enough to fly. In this way a single pair of wrens will destroy many hundred insects every day.

8. The wren quarrels with other birds if they try to build nests too near it. It will often take the nest of the martin or bluebird when the owner is away, and hold on to it.

9. At one time a wren was seen to go into the nest which a pair of martins had just finished. When the martins came back, it beat them off. The martins kept watch, and, when the wren was out, they went back into their box, and built up a strong door, so the wren could not get in.

10. For two days the wren tried to force its way in; but the martins held on, and went without food during that time. At last the wren gave up, and built a nest elsewhere, leaving the martins in quiet possession of their own nest.

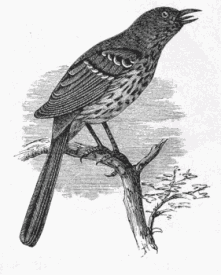

1. The thrush is one of our best singing birds. It does not come near the house, like the wren, but it builds its nest in thickets and quiet places, where it is not liable to be disturbed.

2. It lives on berries and insects. It is a shy bird; but in the edge of the wood its song may be heard often during the day, becoming more frequent toward evening.

3. The mother bird lays from four to six eggs,[50] and both father and mother sit on the eggs and take care or the young.

4. The thrush is double the size of the wren, and nearly all the kinds are brown in color, some having their wings tipped with red or yellow.

5. The brown thrush, or brown thrasher as it is sometimes called, is bold and strong, and when a cat or fox comes prowling about near its nest it flies at him so savagely that he is glad to get out of the way.

6. It is not afraid of hawks, and it has a special spite against snakes that come around to rob its nest. When it sees a snake, it flies at him with great rage, and kills him or drives him off.

7. The hermit thrush lives in the dark, thick woods, and many people think its song, which is heard in the evening twilight, is sweeter than that of any other bird.

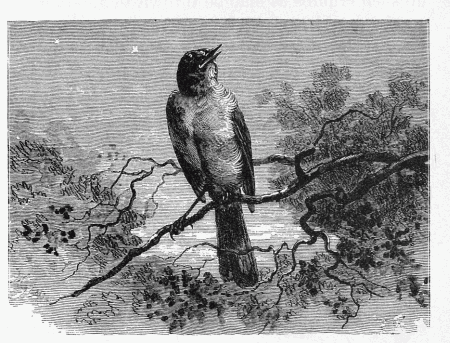

So says the old song, but Robin sings just as sweetly all the summer long.

2. The robin is better known than most birds. It comes earliest in the spring, and goes away late in the fall. It builds its nest near houses, and[52] every day flies about the garden and yard, picking up such crumbs as may be thrown to it. It is the special favorite of children.

3. It is three times as large as the wren. Its color is a dark olive-gray above, with a red breast. Its head and throat are streaked with black and white.

4. It has a pleasant, home-like little song, and its notes vary with the weather, being much more joyous on bright, warm days.

5. The English robin is about half the size of ours, but has the same gray coat, and a somewhat redder breast.

6. It lives about yards and gardens, and wakes people up in the morning with its charming little song. It does not like to have other birds, or cats, come too near its nest; and when they do, it flies at them with great rage.

7. When the robin has once built its nest it[53] is not easily driven away. Once, a wagon loaded for a journey was left standing a few days in a yard. Under the canvas covering of this wagon a pair of robins built their nest.

8. After the wagoner started, he found the nest, with the young just hatched. The old birds went along, taking turns in brooding the young ones and in flying about for worms.

9. The wagon went a hundred miles and back, and, by the time it came back to the place of starting, the young birds were pretty well grown. You may be sure that the wagoner did not let any one disturb the birds on the route.

10. One spring a pair of thrushes were seen about the garden of a country house. One of them seemed ill, and could hardly get about. It would hop a little way, and then stop, too tired to go farther.

11. Her mate took good care of her. He got her into a safe place in a tree, brought her worms and insects, and cheered her with his music.

12. In the course of three or four days she got better; and one day, when he came with her dinner, she flew a little way to meet him, and in a short time they went off together, each singing a joyous song.

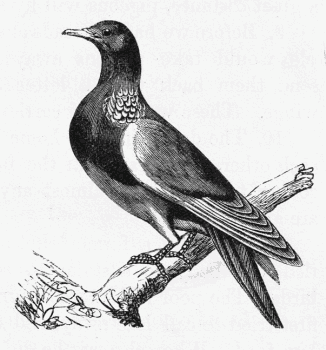

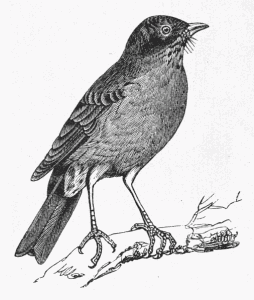

1. The English blackbird is about the size of our robin. It is a cousin to the thrush, and sings a sweet little song.

2. It builds its nest in trees and hedges near houses, and all day long you can hear its song as it goes about busy in taking care of its family.

3. One spring, a couple of blackbirds built their nest on a tree that stood by the garden fence, near a cottage. All went well with them until the eggs were hatched, and four little birds filled the nest.

4. But the old cat had been on the watch, and[55] had found out where the nest was. One morning, while the mother bird was out after worms, the cat thought it a good time to make her breakfast on young birds. So she climbed to the top of the fence, and crept along on its narrow edge until she came almost in reach of the nest.

5. But Mr. Blackbird, who had been watching her for some time, with a loud cry of rage now made a dash at her and hit her square in the face.

6. The cat tried to strike him with her claw; but she had to hold on to the fence to keep from falling, and so could not spring upon him.

7. After hitting her several times, the bird lit upon her back, and struck her with his wings, and pecked her with all his might.

8. The cat tried to turn and get at him, but lost her hold and rolled off the fence. But the bird kept flying at her until she ran away. Then he perched on a rail and sang a joyous song.

9. The next day the cat came creeping along again toward the nest; but the blackbird was ready for her, and gave her another good drubbing until she again fell off the fence and ran away.

10. Afterward, the bird took to hunting the cat every time she came about, until he finally drove her entirely out of the garden.

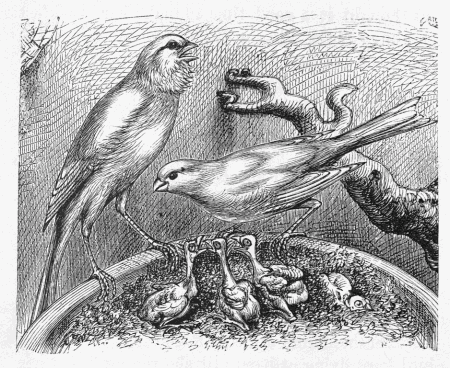

1. Canary-birds were first found in a warm region, and they can not live out-of-doors in our country. They have lived so long in cages, and been taken care of, that now they have lost the power to get their own living, and, if turned out, would soon starve to death.

2. The canary is one of the sweetest of all the bird singers, and it is so pretty in its ways, and so[57] clean, that it is more often made a pet than any other bird. It has a sweet song of its own, but it is easily taught to sing a great many new notes. The songs of the canary, as we hear them, are very different from its song when wild.

3. A canary will often become so tame that it will fly about the room, come when called, perch on its mistress's finger, and eat out of her mouth.

4. The canary lays from four to six eggs, and hatches them in about two weeks. Both father and mother bird take care of the young.

5. In a large cage with two parts, two finches were in one end and two canaries in the other. The finches hatched out their eggs, but did not feed their young ones enough. The father canary, hearing their hungry cries, forced himself between the bars into their part of the cage, and fed them. This he did every day, till the finches were shamed into feeding the little ones themselves.

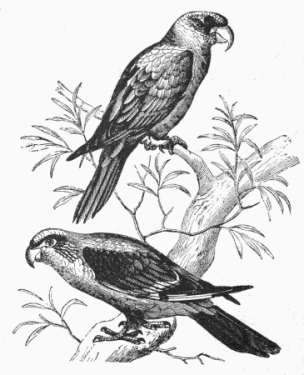

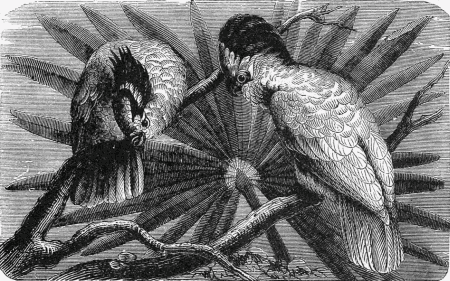

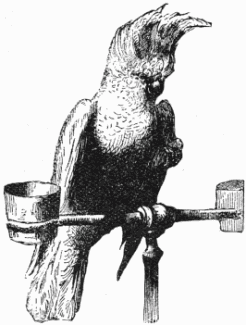

1. Next to the canary, the parrot is the pet bird of the house-hold. It is kept for its bright colors, its curious ways, and its power to talk.

2. The parrot is about the size of the dove. In color, those that we see most often are green or gray. Some parrots are of a bright red, and others are gay with bright green, red, and yellow.

3. The parrot has a thick, strong, and hooked bill. It is so strong that it can take hold of[61] the branch of a tree and hold itself up, and with it it can crack the hardest nuts.

4. It came from a warm region, and must have a warm room in winter, or it will die. It lives on nuts and seeds, but when kept in the house it will sometimes eat meat.

5. The parrot learns to love its master and those that take care of it; but it is often cross to strangers, and will give them a terrible bite with its hooked bill if they come too near.

6. Like other birds, the parrot has four toes on each foot; but two of these are in front and two behind. The toes are very strong, and with them it can grasp things as we do with our hands.[62]

7. With these toes it climbs easily, reaching up first one foot and then the other, and sometimes taking hold with its bill. When eating, it holds its food in its claw, biting off pieces to suit it.

8. When wild, the voice of the parrot is a loud, unpleasant scream, and it does not forget this scream in its new home. But it also learns to talk, and it may be taught to say many words as plainly as boys or girls speak.

9. Parrots can whistle, and some have been taught to sing. They need good care, which they repay by their pleasant ways and curious tricks. Some of the parrot kind are called paroquets, and some are called cockatoos.

10. This curious story is told of a parrot: One day, Sarah, a little girl of eight years, had been reading about secret writing with lemon-juice.

11. Not having any lemon, she thought she would try vinegar. So, after dinner, she took a cruet, and was just pouring the vinegar into a spoon, when her parrot sang out, "I'll tell mother! Turn it out! Turn it out!"

12. The child, thinking the parrot would really tell her mother, threw down the cruet and the spoon, and ran away to the nursery as fast as her legs could carry her.

1. A green parrot, kept in a family for a long time, became so tame that she had the free run of the house. When hungry, Polly would call out, "Look! cook! I want potato!"

2. She was very fond of potatoes, and if anything else was put in her pan she would throw it out, and scream at the top of her voice, "Won't have it! Turn it out!"

3. The children in the house were all girls, and Polly for some reason had taken a great dislike to boys. One day some boys came on a visit, and,[64] as boys do, made a great noise. This was too much for Polly, who screamed out, "Sarah! Sarah! here's a hullaballoo!"

Cockatoo

Cockatoo4. Polly was very fond of the mistress of the house, and was always on the lookout for her at the breakfast-table.

5. If she did not come down before the meal was begun, Polly would say, in the most piteous tone, "Where's dear mother? Is not dear mother well?"

6. Another parrot had learned to sing "Buy a Broom" just like a child. If she made a mistake, she would cry out, "O la!" burst out laughing, and begin again on another key.

7. This parrot laughed in such a hearty way that for your life you could not help joining with her, and then she would cry out, "Don't make me laugh! I shall die! I shall die!"

8. Next she will cry; and if you say, "Poor[65] Poll, what is the matter?" she says, "So bad! so bad! Got a bad cold!" After crying some time, she grows more quiet, makes a noise like drawing a long breath, and says, "Better now," and then begins to laugh.

9. If any one vexes her, she begins to cry; if pleased, she laughs. If she hears any one cough or sneeze, she says, "What a bad cold!"

10. Here is a story which a boy tells of a parrot: "Poll was a great friend of mine, and had been in the house ever since I could remember.

11. "Offy was a pug-dog, so fat that a little way off he looked like a muff to which some one had tied a tail. I hated Offy, for he was always barking at me, and I think he knew I was afraid of him. Poll hated Offy, too, and with good reason.

12. "The pug was always sneaking round, and stealing the cake which Poll had laid aside for her supper. Poll missed her cake and was furious, but the dog licked his chops and laughed.

13. "One day Poll hid herself on the top of the cupboard and watched. Offy came as usual to steal her cake, when she pounced on his back and gave him such a drubbing that he never stole any more from her."

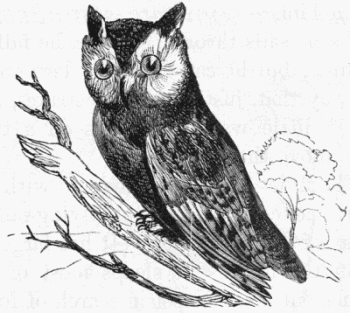

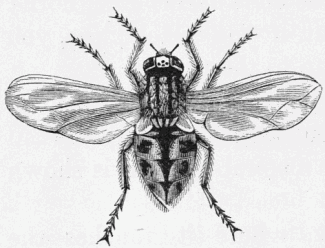

1. Sometimes we see a bird come sweeping down into the farm-yard and seize a chicken and fly away with it, and sometimes we see the same bird pounce down upon a robin, a wren, or a dove, and carry it off.

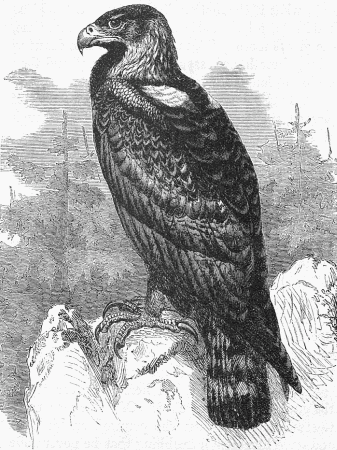

2. This robber is the hawk. Another robber, larger and stronger than the hawk, is the eagle, which we see on the opposite page. Let us look at them.[68]

3. They are covered with mottled black and white feathers, which make them look gray. In some kinds of hawks, the breast is nearly white.

4. They have very strong wings, and can fly far and fast without being tired. The beak is short, strong, and pointed, and hooked at the end. It is made so that it can easily tear flesh from the bones of animals.

5. The claws, or talons, are strong, sharp, and hooked, and the leg above is short and strong.

6. The hawk preys upon chickens, the smaller birds, squirrels, and other small animals. The eagle will carry off hens, turkeys, rabbits, lambs, and the like. They have been known to carry off a baby.

7. The hawk and the eagle seize their prey, not with their beaks, but with their talons. They[69] drive their long, sharp nails into the flesh, and the chicken or rabbit is dead in a few minutes.

8. They carry their prey to their nests, and there they hold it in their talons, and, with their beaks, tear off the flesh, which they eat, and feed to their young.

9. Both the hawk and the eagle have sharp eyes, and they can see a long distance. If we should see an eagle in a cage, we would find that its eyes are bright and a deep yellow in color; but they look wild and cruel, and we do not like to go very near it.

10. The fish-hawk preys upon fish. He sails slowly over the water until his sharp eyes see a fish, and then he dives down so straight and swift that he rarely misses.

11. Sometimes, when he comes up from the water, an old eagle that has been on the watch pounces upon him. The hawk tries to get away, but the eagle soon overtakes him.

12. With an angry scream the hawk drops the fish, and the eagle swoops downward so quickly that he catches the fish before it reaches the water. With his prey in his talons, he then soars away to his nest in the tree-tops, or high up among the rocks on the mountain-side.

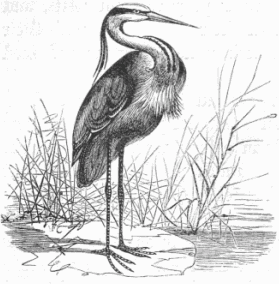

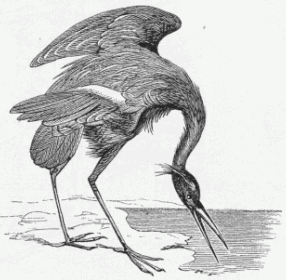

1. We have here the picture of a heron, a very curious bird. It has long legs, a large body, a long neck, and a long pointed bill.

2. Its toes are long and pointed, and when spread out they cover a large space. It can turn its neck and bill so that sometimes it looks as if it would wring its own neck off.

3. The heron lives on frogs and fish. With its long legs it can wade out in the shallow water, and its toes spread out so it does not sink in the mud.

4. When ready for breakfast, it wades in where the water is half-leg deep. Then it stands so still that the fish, the frogs, and the water-rats will swim all about its legs.[71]

5. All at once, as quick as a flash, down plunges the beak, and up comes a frog from the water, and down it goes, whole, into the long throat. Another comes along, and goes the same way.

6. When it has had enough, it steps ashore, cleans its feathers with its long bill, and goes to sleep standing on one leg. Its middle toe has a double nail, and with this it scratches off the down that sticks to its bill after cleaning its feathers.

7. The heron flies high in the air. When flying, its legs extend out straight behind, and its neck curls over and rests on its back.

8. The stork is another bird with long legs that wades in the water and eats frogs and fish. In Holland, the stork is so tame that it lives in the farm-yard, and often builds its nest on the house-tops.

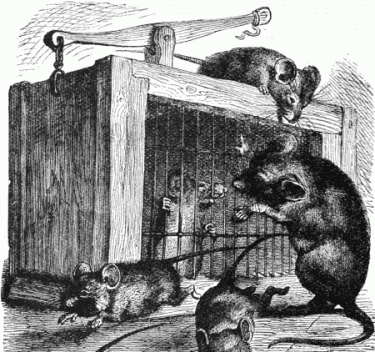

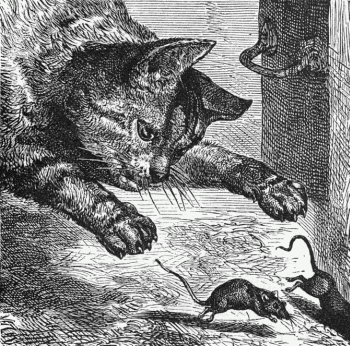

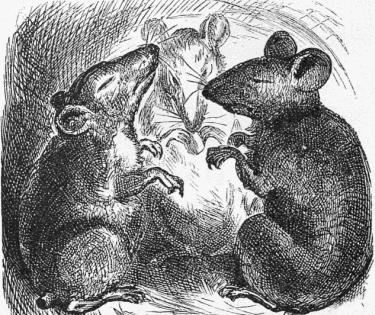

1. Here are some of our near neighbors, little fellows in fur, who are so very friendly that they visit us by night and by day, and seem as much at home in our house as we are.

2. When, in the night, we[75] hear tiny feet as they patter over the floor, or scamper across the pillow, or we find in the morning that the loaf for breakfast has been gnawed and spoiled, we are not apt to feel friendly toward the mouse.

3. But, as he stands here by the trap, let us take a good look at him. We find that he has a coat of fine fur, which he always keeps clean, and a long tail that has no hair. He has whiskers like the cat; sharp claws, so that he can run up the side of a house, or climb anything that is a little rough; and eyes that can see in the night.

4. He has large ears, so that he can hear the faintest sound; and short legs, so that he can creep into the smallest hole.

5. His nose is pointed, and his under jaw is shorter than the upper one. In front, on each jaw, he has two sharp teeth, shaped like the edge of a chisel, and these he uses to gnaw with.

6. These teeth are growing all the while; and if he does not gnaw something hard nearly every day, so as to wear them off, they will soon become so long that he can not use them.

1. Mice increase so fast that, if we did not have some way to destroy them, they would soon overrun the house, so that we could not live in it.

2. They have their homes in the hollow walls, and can go about from one part of the house to the other without being seen; and when they smell food they gnaw a hole through the wall to get at it.[77]

3. They are playful little animals, and may easily be tamed. When a mouse comes into the room where people live, it is ready to run away at once if anything moves.

4. But if all are still, it will scamper about the floor, and look over and smell everything in the room. The next day it will come back, and finally it will play about the room as if no one were there.

5. The mice that run about the house have gray coats; but some mice are white, with pink eyes, and these are often tamed and kept as pets.

6. A lady once tamed a common gray mouse, so that it would eat out of her hand. She also had a while mouse in a cage.

7. The gray mouse was very angry when he saw the lady pet the white mouse; and one day he some way got into the cage, and when the lady came back into the room, she found the white mouse was dead.

8. Music sometimes seems to have a strange effect upon a mouse. At one time, when a man was playing upon his violin, a mouse came out of his hole and danced about the floor. He seemed almost frantic with delight, and kept time to the music for several minutes. At last he stopped, fell over on the floor, and they found he was dead.

1. White-paw was a young mouse that lived with his mother. Their home was in a barn, behind some sacks of corn, and a very nice home it was.

2. When a sunbeam flashed in upon them at midday, "That was the sun," said Mrs. Mouse. When a ray of the moon stole quietly in, "That is the moon," said the simple-minded creature, and thought she was very wise to know so much.[79]

3. But little White-paw was not so contented as his mother. As he frisked and played in his one ray of sunshine or one gleam of moonlight, he had queer little fancies.

4. One morning, while at breakfast on some kernels of corn and sweet apples which his mother had brought home, he asked:

5. "Mother, what is the world?"

6. "A great, terrible place!" was the answer, and Mrs. Mouse looked very grave indeed.

7. "How do you know, mother? Have you ever been there?" asked the youngster.

8. "No, child; but your father was lost in the great world, my son," and Mrs. Mouse's voice had a little shake in it.

9. "Ah!" said the son, "that was for want of knowing better."

10. "Knowing better! Why, he was the wisest mouse alive!" said the faithful Mrs. Mouse.

11. "I could not have been alive then," thought White-paw to himself. Then he said aloud, "Mother, I have made up my mind to go and see the world; so good-by!"

12. His mother wept. She tried to have him stay at home and be content—but all in vain; so she gave him a great hug, and he was off.

1. He had not gone many steps when he met Mr. Gaffer Graybeard, a wise old mouse, and a great friend to the family.

2. "Well, where are you off to, Mr. Pertnose?" he asked, as the young traveler was whisking by. "I'm off to see the world," was the answer.

3. "Then good-by, for I never expect to see you again; but take an old mouse's advice, and beware of mouse-traps." "What are mouse-traps?"[81] asked White-paw. "You will know when you see them," was the answer.

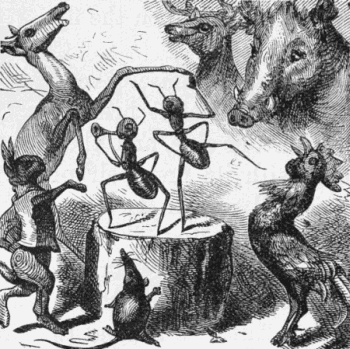

4. White-paw went on his way, and just outside he met another young mouse who had also started to see the world, and the two went on together.

5. "Oh, how big the world is!" said White-paw, as they went into the farm-yard, and began to look about them.

6. "And what queer creatures live in the world!" said the other, as the cocks crowed, the hens clucked, the chickens peeped, the cow lowed, the sheep bleated, the pigs grunted, and the old house-dog barked.

7. "If we are to find out about the world, we must ask questions," said White-paw.

8. So the two friends went about, stopping every now and then to admire or wonder at the new things they saw every moment.

9. Soon they came across a friendly-looking pig. "Please, sir," asked the wee simple things, "are you a mouse?"

10. The pig looked down to them through his "specs" as he heard the question in the tiny little squeaking voice, and he grunted a little as he replied:[82]

11. "Yes, if you like to call me so," and the two friends went on.

12. In a little while they came up where the old cow was feeding; and White-paw, taking off his hat, said, "Please, are you a mouse?"

13. The old cow was too busy to answer such questions, but she shook her head in such a way that the travelers were glad to get off safe.

14. "There are great friendly mice, and great unfriendly mice, in the world!" said White-paw, as they went on their way.

15. Next they met a motherly old hen, who was busy in scratching up food for her chickens; and White-paw asked, "Please, ma'am, are you a mouse?" "We don't mind what folks call us," said the old hen, giving them a friendly wink.

16. As they went on they learned a great many things about the world; but as yet White-paw had not heard one word about a mouse-trap.

17. Having gone around the farm-yard, White-paw and his friend went through the gate toward the house. Here they met the dog, and asked the same question that they had asked before.

18. But the dog barked and snapped so that they could not ma ke him hear, and they ran away in terror.

1. In their haste the two friends bolted into the kitchen of the farm-house, where an old tabby-cat lay dozing before the fire. But when they came in she arose to meet them.

2. "What a polite fat mouse!" thought White-paw. "Please, ma'am—" But pussy's eyes were fixed upon him with a horrid glare, and he could not go on.

3. Alas! his poor little friend! There was a[84] cry and a crunching of bones, and White-paw just escaped through a hole into the pantry.

4. When he had in part got over his fright, he smelled toasted cheese—something he had heard of but never tasted. He sniffed about, and soon saw it in a little round hole.

5. By this time he was very hungry, and he reached out for the dainty morsel; but there was a sudden click, and he turned back—but too late! His tail and one of his legs were caught by the cruel teeth of a trap.

6. He pulled with all his might, but could not get away. He heard a little squeak, and an old mouse came limping up with only three legs.

7. "Pull hard, my son; better lose a leg and tail than your life. See! I was caught like you. How came you here?" he asked.

8. "I came to see the world, and 'tis a terrible place!" As White-paw spoke, he pulled himself free, but left one paw and the point of his tail in the trap.

9. The two hopped off together, and, after some friendly advice from the old mouse, White-paw limped away to his home, and soon found himself by his mother's side, where he could have his wounds dressed, and rest in peace.

1. "My dear son, what is the world like?" asked Mrs. Mouse, after she had hugged White-paw, and set his supper before him.

2. "Oh, it's a grand place! There are great black mice, and great white ones, and great spotted ones, and great friendly mice with long noses, and great uncivil mice with horns.

3. "Then there are queer mice with only two[86] legs, and some terrible mice that make a great noise." At this moment, Gaffer Graybeard came in, and White-paw said, "Sir, I've learned what a mouse-trap is." "Ah! then," said the sage, "you've not seen the world in vain."

1. Some kinds of mice live in the fields and woods, and never come into the house. The tiny little harvest-mouse has its home in the grain or thick grass, and feeds upon grain and insects.

2. It makes a nest of grass neatly woven together, and places it on the stalks, about a foot from the ground, where it is out of the way of the wet.

3. The nest is round, and about the size of a large orange. When the mother mouse goes away, she closes up the door of her nest, so no one can see her little ones.

4. The harvest-mouse runs up the corn and grass stalks easily. In climbing, it holds on by its tail as well as by its claws. The way it comes down from its nest is very curious. It twists its tail about the stalk and slides down.

5. Another of the field-mice is the dormouse, that lives in the woods. It has a bushy tail, and makes its nest in hollow trees. It lives upon nuts and fruit. As cold weather comes on, it rolls itself up in a ball, and sleeps until spring.

6. Once a dormouse was caught and kept in a cage, when it became quite tame, and a great pet with the children. One day it got out of its cage,[90] and the children hunted all over the house, but could not find it, and gave it up as lost.

7. The next day, as they sat down to dinner, a cold meat-pie was put upon the table. When it was cut open, there was the dormouse in the middle, curled up, and fast asleep.

8. The deer-mouse lives mostly in the fields, but it also makes its home in barns and houses. Its back and sides are of a slate color, but the under part of its body, and its legs and feet, are white. It is sometimes called the white-footed mouse, or wood-mouse. It builds a round nest in trees, that looks like a bird's nest, and it lives upon grain, seeds, and nuts.

9. This mouse seems fond of music, and once in a while one sings. Its song is very sweet, somewhat like that of a canary, but not so loud. Mr. Lockwood's singing mouse would keep up its wonderful little song ten minutes without stopping.

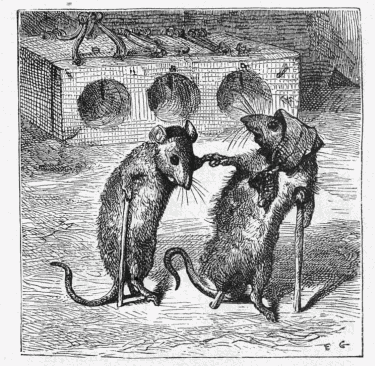

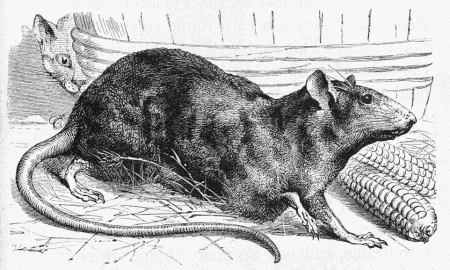

1. The rat looks like a very large mouse. It has the same kind of chisel-teeth, sharp claws, and long tail, and it lives very much in the same way as a mouse.

2. It eats all kinds of food, and will live where most other animals would starve. Its teeth are strong, and it can gnaw its way into the hardest nuts, or through thick boards.

3. The claws of the rat are sharp, so that it can run up the side of a house, or up any steep place where its claws will take hold. When at[92] the bottom of a barrel, or kettle of iron, brass, or tin, it can not climb out.

4. The hind feet of the rat are made in a curious way: they can turn round so that the claws point back. This enables a rat, when it runs down the side of a house, to turn its feet around and hold on, while it goes down head foremost.

5. The tail of the rat is made up of rings, and is covered with scales and very short hair. The rat uses it like a hand to hold himself up and to take hold of things.

6. Rats live in houses and barns, or wherever they can get enough to eat. In cities, they get into drains, and eat up many things which would be harmful if left to decay.

7. They are great pests in the house, running about in the walls, gnawing through the ceilings, and destroying food and clothing.

8. When rats get into a barn, they are very destructive. They eat up grain, and kill young chickens; and they often come in droves, when the pigs are fed, to share the food.

9. Rats increase very fast. Each mother rat produces fifty young ones in a year; and if we did not take great pains to destroy them, they would drive us out of our homes.

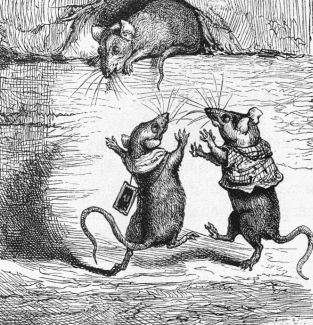

1. Rats are very fond of eggs; but they do not like to be disturbed while eating, and so they contrive to carry the eggs to their nests, where they can enjoy their feast in safety.

2. In carrying off eggs, several rats will often go together. A rat will curl his tail around an egg, and roll it along. Coming to a staircase, they will hand the egg one to another so carefully as not to break it.

3. A lady once watched the rats, which were at work at her egg-basket. One rat lay down on[94] his back, and took an egg in his arms. The other rats then seized him by the head, and dragged him off, egg and all.

4. Rats can easily be tamed, and even a dog can scarcely love its master better than a rat does when it is treated kindly. Mr. Wood tells this story of some tame rats:

5. "Some young friends of mine have a couple of rats which they have tamed. One, quite white, with pink eyes, is called 'Snow,' and the other, which is white, with a brown head and breast, is named 'Brownie.'

6. "The rats know their names as well as any dog could do, and answer to them quite as readily.

7. "They are not kept shut up in a cage, but are as free to run about the house as if they were dogs or cats.

8. "They have been taught a great number of pretty tricks. They play with their young master and mistress, and run about with them in the garden.

9. "They sit on the table at meal-times, and take anything that is offered to them, holding the food in their fore paws and nibbling it; but never stealing from the plates.

10. "They are very fond of butter, and they[95] will allow themselves to be hung up by the hind feet and lick a piece of butter from a plate, or a finger.

11. "Sometimes these rats play a funny game. They are placed on the hat-stand in the hall, or put into a hat and left there until their owners go up-stairs.

12. "They wait until they are called, when they scramble down to the floor, gallop across the hall and up the stairs as fast as they can go.

13. "They then hunt until they find their master, climb to his shoulder, and search every pocket for a piece of bread and butter, which they know is there for them.

14. "They are very clean in their ways, and they are always washing their faces and brushing their mouths and fur with their paws, just as cats do.

15. "It is very amusing to see them search the pockets of those they know: diving into them, sniffing at every portion, and climbing out in search of another.

16. "They will not come at the call of a stranger, nor play any of their tricks with him; but they will allow themselves to be stroked and patted, and they never try to bite."

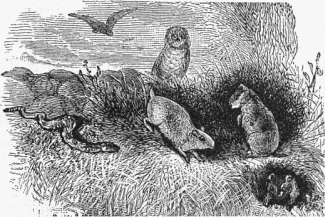

1. We here come to the rabbit, one of our innocent and harmless friends that is a great pet with children. It is very timid and easily scared, but when treated kindly it becomes tame.

2. The rabbit is about the size of a cat, and has a short tail. The wild gray rabbit is not so large as the tame rabbit which we have about the house.

3. The rabbit has sharp gnawing-teeth like the rat and mouse, and it gets its food and eats it in the same way.

4. It eats the leaves and stalks of plants, and is very fond of cabbage, lettuce, and the tender leaves of beets and turnips. It sometimes does much damage by gnawing the bark of young fruit-trees.[97]

5. It has whiskers like the cat, so that it can crawl into holes without making a noise.

6. Its fore feet are armed with strong, blunt claws. It can not climb, but it is able to dig holes in the earth.

7. Our wild rabbit lives in the grass, or in holes which it finds in stumps and hollow trees, and among stones; but the English rabbit digs a hole in the soft ground for its home.

8. The holes that the rabbits dig are called burrows; and where a great many rabbits have burrows close together, the place where they live is called a warren.

9. The burrows have two or more doors, so that if a weasel or some other enemy goes in at one door, the rabbit runs out at the other. In a warren, many burrows open into one another, forming quite a village under ground.

10. The rabbits choose a sandy place for a warren, near a bank, where they can dig easily, and where the water will run off. In these homes they sleep most of the time during the day, and come out by night to feed on such plants as they can find. When wild, the dew gives them drink enough; but when fed with dry grain food, they need water.

1. The rabbit has large ears, and can hear the slightest sound. When feeding or listening, the ears stand up or lean forward; but when running, the ears lie back on its neck.

2. When the rabbit hears any sound to alarm it, it never stops to see what is the matter, but scuds away to its hole, plunges in, and waits there until it thinks the danger has passed away.

3. Then it comes to the mouth of the burrow, and puts out its long ears. If it does not hear anything, it raises its head a little more, and peeps[99] out. Then, if it does not see anything out of the way, it comes out again and begins to feed.

4. Rabbits increase so fast that if they were not kept down they would soon eat up all the plants of our gardens and fields. So a great many animals and birds feed upon them, and a great many are killed for their meat and fur.

5. When first born, the little rabbits are blind, like puppies and kittens, and their bodies are naked. The mother rabbit makes a warm nest for them of dried leaves, and she lines it with fur from her own body.

6. In about ten or twelve days the little rabbits are able to see, and in a few weeks more they are quite able to take care of themselves.

7. The rabbits that we have for pets are of various colors, but mostly white or black, or part white and part black. They do not dig into the earth as the wild ones do, but they love to have their homes in snug little places, like holes.

8. The hind legs of the rabbit are longer than its fore ones, and, instead of walking, it hops along. When it runs, it springs forward with great leaps, and gets over the ground very fast.

9. Pet rabbits that have large ears sell most readily. One of the rabbits, in the picture, looks[100] very curious with one long ear lopped down over his eye, and the other standing up straight.

10. When they live out in the woods and fields, rabbits have many cruel foes. One of the worst of these is the owl, who, prowling about in the dark, springs upon the poor rabbit, and breaks its neck with one fierce stroke of its sharp bill.

11. As a rabbit can not defend itself by fighting, it has long ears to detect danger, and swift feet to get away from an enemy. When alarmed, away it goes, with a hop, skip, and jump, and like a flash passes out of sight.

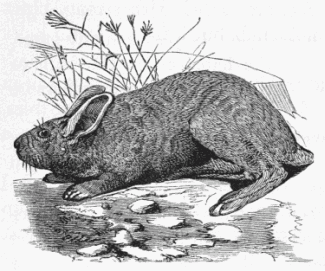

1. The hare looks very much like a large rabbit. It has the same kind of teeth, and eats the same kind of food. Its legs are longer than those of the rabbit, and it runs in the same way, only faster.

2. It does not burrow in the ground nor crawl into holes, but it makes its home in tufts of long grass. As it lies in the same place for a long time, it makes a little hollow, which is called its form.

3. It has larger ears than the rabbit, and seems always listening. It is very timid, and, when it hears any strange sound, away it goes like the wind, running with long leaps.

4. When at rest in its form, it folds its legs under its body, lays its ears back flat on its neck; and, as it is of the color of dried grass, a per[102]son may pass by within a few feet of it and not see it.

5. Its upper lip is divided in the middle, as is also that of the rabbit. It sometimes will fight, and then it hits hard blows with its fore feet, and strikes so fast that its blows sound like the roll of a drum.

6. When the snow falls, the hare sits in its form, and is covered up. But its fur keeps it warm, and the heat of its body melts the snow next to its skin, so that it sits in a kind of snow-cave, the snow keeping off the cold wind.

7. When dogs chase a hare, it runs very fast until the dogs are close to it, when it stops suddenly. This it can do, as it runs by leaping with its long hind legs.

8. The dogs can not stop so quickly, and run past. The hare then starts off in another direction, or doubles, as we say, and so gains upon the dog. In this way it often escapes, and then it goes back to its form.

9. The hare is sometimes tamed, and it soon learns to know its friends; but it is a troublesome pet, as it gnaws the legs of the chairs and tables, and destroys the trees in the yard by gnawing off the bark near the roots.

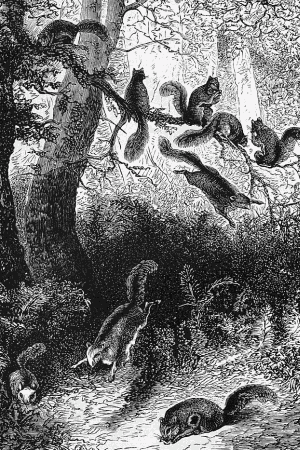

1. Here comes the squirrel—the little fellow that frisks and gambols so prettily over trees and hedges, and that chatters to us as we take a walk in the woods or fields. He is afraid to let us touch him; but he will let us come quite near, as he knows he can easily get away.

2. As we see him scampering along on the fences or trees, the first thing that we notice is his long bushy tail, which he coils up over his back.

3. But we will find one in a cage, and then we will take a closer look. We find that he has[105] chisel-teeth, like the rat and rabbit, and then we know that Mr. Squirrel eats something that he must gnaw.

4. His toes are not strong, like those of the rat or rabbit, but they are long and slender, and we know that he does not dig holes in the ground. The nails are not strong enough to catch prey, but are long, thin, sharp, and bent at their tips.

5. Then we find that the squirrel can turn all his toes around so that the nails point backward, and we see that he is made for running up and down trees, where he has his home.

6. Now we see what he does with his sharp cutting-teeth. He lives upon nuts, and his teeth are for gnawing through the hard shell, to get at the kernel inside.

7. The ears of the squirrel are of moderate size. The rabbit and hare live upon the ground, and, if they did not have large ears and sharp hearing, they would be killed by dogs and other enemies. But the squirrel has his home in trees, out of reach of animals that can not climb; so it does not need such sharp hearing to save itself.

8. When in his home in the trees, the squirrel feels safe; so he curls his tail over his body and head to keep warm, and goes to sleep.

1. As the squirrel is made to climb trees and live on nuts, he builds his nest there, and makes the tree his home. He finds some hollow place in the tree, or he builds where some large limb branches off, so that his nest can not well be seen from below.

2. His nest is made of dried leaves and bits of moss. His summer home is high up on the tree, where he has plenty at air; but his winter nest is as snug in some hole as he can make it.

3. In the fall, the squirrel gathers nuts and corn, and stores them up near his winter nest. Then, when cold weather comes on, he crawls into his bed of leaves, curls up, and goes to sleep.

4. Now and then, in the winter, he wakes, crawls to his store and has a dinner, and then goes to sleep again. When the warm days of spring come on, he wakes up fully, and is ready for his summer's work and play.[107]

5. When the squirrel eats a nut, he takes it in his paws, sits up straight, with his tail curled over his back, and nips off the shell in little bites, turning it about as easily as we could with our hands.

6. The squirrels that we see most often are the little chattering red squirrel, and the gray squirrel, which is about twice as large. In the West and South, a large squirrel, that is partly red and partly gray, is called a fox-squirrel. All these squirrels have fine little rounded ears, and large eyes, so placed that they can look all around.

7. The English squirrel is most like our red squirrel. It is of the same color, but a little larger, and has pointed ears, with a long tuft of hair standing up from the top.

8. The teeth of the squirrel grow, and he wears them off by gnawing nuts. If, when not in his winter's sleep, he should stop gnawing something hard for a week or two, his teeth would become so long that he could not use them again.

1. Here we have the most curious squirrel of all—one that can fly or sail through the air. It is about the size of the common red squirrel, and nearly of the same color, but lighter upon the lower part of its body.

2. It has a loose skin on each side, running from its fore legs to its hind ones. When it is at rest, or when it walks and runs, this skin hangs like a ruffle. But when Mr. Squirrel wants to go fast, or on a long journey, he scampers to the top of a tree and spreads out his legs, drawing the loose skin tight like a sail.

3. He then gives a leap, and away he sails into the air, striking near the foot of another tree a long distance away. He runs up to the top of this[110] tree, and away he goes again, so fast that nothing can catch him.

4. As he sails through the air, he falls toward the ground; but he can carry his legs and tail in such a way that, just before he strikes, he shoots upward a little way, and lands on a tree, some distance above the ground.

5. The flying squirrel is covered with soft, fine fur, but the covering of the flying-sail is finer than that of any other part. It has large eyes, for seeing in the night. It sleeps most of the day, and comes out after sunset in search of food.

6. A squirrel makes a pretty pet, and sometimes it becomes so tame that it runs about like a dog. A squirrel was once found in its nest before its eyes were opened, and brought to the house.

7. It became very tame, and, after it grew up, it would watch its master when he went out, and get into his pocket, where it would stay and peep out to the people it met.

8. When they came to a country place, the squirrel would leap out, run along the road, climb to the tops of the trees, nibble the leaves and bark, and then scamper after his master, and nestle down into his pocket again.

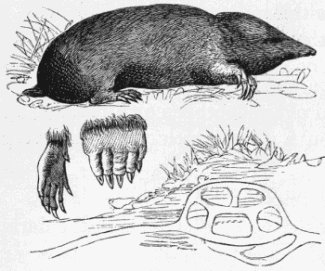

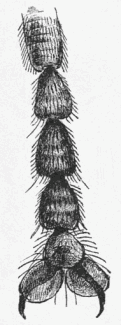

1. Here we have the mole—a very curious animal. It is about the size of a rat, and is covered with a dark brown coat of fine fur. The fur does not lie back, as on the cat, but stands out straight from the body.

2. The legs of the mole are short, and are so formed that it can not stand upon them and raise its body from the ground.

3. The fore legs are large and strong, and each paw has five toes, armed with strong nails. When its toes are together, its fore paw is like a spade; and when they are spread apart, it is like a fork.

4. It has small ears, which are out of sight in the fur; and something like eyes, also deep in the fur, so that it can not see, or at most it can only tell when it is light and when it is dark.[115]

5. Its nose is pointed, and its teeth are all sharp, like those of the cat, but are so small that they look like the points of white needles.

6. What does this little blind animal, that can only creep along, do? how can he get a living? and how does it get away from enemies?

7. We see that all its limbs are so small and set so close to its body that it can easily creep through small holes. Its hair stands out, so that it can crawl both ways.

8. It has no eyes, because it lives in the dark, and does not need to see to get its food.

9. Its nose is pointed and keen, so that it gets its food by scent instead of sight. By scent, too, it can tell when danger is nigh.

10. Its fur is fine and close, so that it is able to live in very damp places, and the wet does not get through to the skin.

11. Its ears and eyes are deep down in the fur, so that, in crawling through a hole, no dirt or dust can get into them.

12. Its teeth are not chisel-shaped, for gnawing, but are sharp and pointed, like the teeth of animals that live on flesh; but they are so small that they would break in trying to eat the bones of even a mouse.

1. As the mole is not made for the sunlight, it must live below ground. With its strong fore paws it digs into the earth, and it can dig so fast that anywhere in the grass it will get out of sight in about a minute.

2. When it is above ground and it scents any danger, it does not run or climb, but it digs; and, when once under ground, it can keep out of the way of almost any enemy.[117]

3. As it digs forward, it pushes the dirt backward, and it will go a long way in a little while. Its hind legs drag behind, and, as they have little to do, they are weak.

4. It digs along in the dark when its keen little nose scents a worm or a grub; this it pushes into its mouth with its paw, and eats in an instant.

5. The meat which it finds below ground has no bones; so its small teeth are all that it needs to chew with. In some safe place, nearly always at the foot of a tree, the mole throws up a little mound of dirt, and in the middle of it builds its nest of dried grass.

6. Then it makes tunnels all around, not any one leading straight up to the nest. In the picture we see the mole's nest and the tunnels leading to it. The mole drinks a great deal, and in its tunnels it digs wells where it can go down and find water.

7. In the summer it keeps near the top of the ground; but in winter it digs down deeper, to find grubs, and because it is warmer.

8. In digging under ground, the mole destroys the roots of grass and plants, and does some damage; but it does much more good, by destroying the grubs which live on the roots of plants.

1. We find in the woods a curious animal called a hedgehog, but which is really a porcupine. The hedgehog is found in Europe, and lives upon insects; the porcupine lives in quite a different way.

2. The porcupine is a little larger than the rabbit. It has short legs, sharp claws, and a short, broad tail. Like the rabbit, it has chisel-teeth for gnawing.

3. It climbs easily; but it moves slowly, both in walking and climbing. Its food is mostly the inside bark of trees. It climbs a tree, and seldom leaves until it has stripped off most of the bark.

4. As it can not run, it has a curious way of defending itself. Besides a coat of warm, soft fur, its back and sides are covered thick with sharp-pointed quills, from two to three inches long.[119]

5. When the porcupine is feeding or going about, these quills lie back flat, like hair; but when there is any danger, they stand out straight. Upon the approach of an enemy, it folds up its paws, curls its head under its fore legs, and shows itself a bundle of sharp quills.

6. Should a dog or hungry wolf then snap at it, the quills get into his mouth, and stick there. Each quill has barbs like a fish-hook, and many an animal has died from the quills working into its flesh after having tried to bite a porcupine.

7. The porcupine can also throw up its back or strike a heavy blow with its tail, driving the quills into the flesh of its enemies.

8. The quills easily break off at their blunt end, and they grow like the hair; so the porcupine has a plenty for use at all times.

9. When men hunt the porcupine, they take care not to get a blow from the tail, and then they watch their chance, and strike the animal on the nose with a club, which kills it at once.

10. The porcupine builds its nest in hollow trees. In the winter it sleeps most of the time, only coming out once in a while to get something to eat.

1. The woodchuck is about twice the size of the common rabbit. Its body is thick, and it has short legs, armed with long, naked nails.

2. It has small, round ears, and a short, bushy tail. It has a thick coat of coarse fur, long whiskers, like a cat, and chisel-teeth for gnawing. It lives upon fruit and the leaves of plants, and is very fond of red clover.

3. When walking, its hind legs do not stand up like those of a cat or dog; but the leg up to the first joint comes down flat upon the ground.

4. With its strong claws it digs a hole in the ground for a home. It chooses a soft place in a bank, where, at first, it can dig up, so that it will not be disturbed by water. Its home has several[121] entrances, so that, if pursued, it can escape by running in or out. In one of its driest rooms it makes its nest of dried grass; and here it stays in stormy weather, only coming out on pleasant days.

5. Woodchucks are very timid, and, when they come out to feed, one sits up and keeps watch. Should it spy any danger, it gives a kind of whistle, and away they all scud to their holes.

6. When winter comes, the woodchuck rolls himself up in his nest and goes to sleep until spring. He is very fat when he takes to his bed in the fall, but is lean when he comes out ready for his next summer's work.