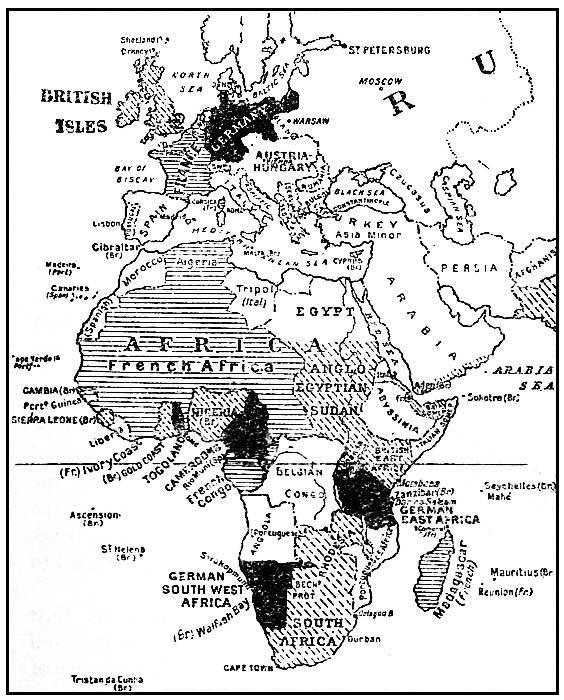

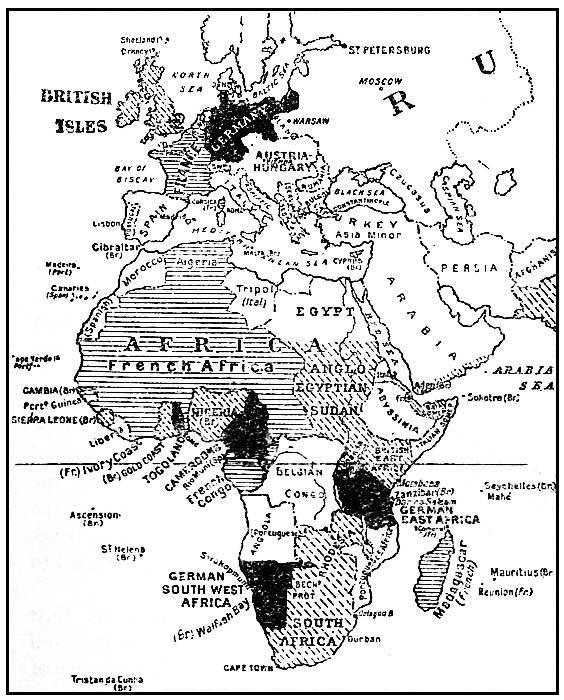

THE GERMAN COLONIES IN AFRICA, 1914.

THE GERMAN COLONIES IN AFRICA, 1914.(Reproduced by permission of The Times.)

Project Gutenberg's Germany's Vanishing Colonies, by Gordon Le Sueur This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Germany's Vanishing Colonies Author: Gordon Le Sueur Release Date: June 26, 2014 [EBook #46103] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GERMANY'S VANISHING COLONIES *** Produced by Matthias Grammel and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Germany's Vanishing

Colonies

BY

GORDON LE SUEUR

AUTHOR OF "CECIL RHODES," ETC.

NEW YORK

McBRIDE, NAST & COMPANY

1915

"ICHABOD"

"Who sows the Wind will reap the Tempest."

By Lieut.-Col. A. St. H. Gibbons, F.R.G.S., F.R.C.I., 23rd (Service) Batt. Roy. Fusiliers (1st Sportsman's)

In giving his readers a very concise and reliable description of "Germany's Vanishing Colonies," the author performs a useful public service. To the travelled man who may have seen something of these Colonies the work carries conviction; for others it has a useful educative value. Knowledge is essential to sound judgment, and although—thanks to the policy of the late Paul Kruger!—a growing interest in our great Empire has permeated all classes in recent years, anything like a comprehensive knowledge of the local conditions and interests of our 12,000,000 miles of Empire is not to be expected until our schools and universities have added to their curriculum systematic instruction in Imperial history and geography.

This book provides important and interesting data on which, at the close of the war, that policy which will determine the status and ownership of Germany's overseas possessions can be built. [Pg 8] To some it may appear that the title of the book implies the dividing of the skin before the lion is killed. Be that as it may; to those who have never felt misgivings as to the ultimate result of this life-and-death struggle for Empire, the speculative element is overshadowed by the supreme importance of inspiring the public mind with an accurate and intelligible grasp of the situation. At times consciously, at others unconsciously, democratic Governments reflect the mind of the community. In due course, our statesmen, working in concert with the Dominion Governments, will be called upon to decide, in the name of the Empire, how far it is politic, either for strategic or economic purposes, to annex all or part of such German oversea possessions as the Allies in council shall decide to be within the British sphere of influence. Let the people in private and public discussion, and through the medium of the Press, come to something like an unanimous decision (and this volume should help them to do so), and so strengthen the hands of the Government when the crucial hour arrives.

No doubt every aspect will be taken into consideration. It will be noted that from the moment Germany decided to establish a colonial Empire her envious hatred of Great Britain took root. She realised that at the British Empire's expense alone could she fully develop her ideal. This feeling has grown and intensified until, in recent years, [Pg 9] she had barely cloaked her ambitious design to replace us as a world Power. When the final word is spoken, and compensation for loss in life and treasure is forced on us by her unscrupulous action is discussed, it will, I think, be ruled that we are more than justified in absorbing, as part payment, those possessions which she had designed to expand at the expense of ours.

Again, British and French Foreign Office dispatches, at the outbreak of war and subsequently, go to show that German diplomacy has been deeply tinged with covetousness and that special kind of hatred born of envy; that she has brushed aside all honourable and humanitarian considerations, and ignored that international code to which she herself had set her seal in favour of a ruthless and unscrupulous application of the principle of brute force. Nor in this case can she offer the "first offenders'" plea. Before the Bar of History she is confronted by Mary Therese and Francis Joseph of Austria, by the quondam Kingdom of Poland, by Denmark and France. Each and all give evidence of forced war as a step towards Prussian expansion.

Can a nation so deeply impregnated with such principles since its cradle days so far reform its political methods as to give reasonable assurance that in thirty or forty years hence she will not reintroduce into the life of nations that spirit and practice of mediaeval barbarism (now better [Pg 10] known as "kultur") which at present racks the civilised world? We may leave it to the Ethiopian and the leopard may reply.

Popular opinion at present seems to indicate an almost unanimous opinion that the roar of the last cannon will ring down the curtain on the German Empire of to-day. That Prussia's Polish province and Alsace-Lorraine will cease to be German may be assumed. Should Denmark recover Schleswig-Holstein, should Hanover regain her independence, and Bavaria repudiate Prussia's uncongenial overlordship it would—in the event of a non-annexation policy being adopted—be difficult to decide to whom the present German Colonies belong—this, of course, irrespective of conquests which have been or may be effected in the meantime, and which, in accordance with the German theory that "might is right," will, ipso facto, have been transferred to the Allies with a "clean title."

History serves to show that to annex territory carrying a considerable homogeneous and hostile population is seldom a success, but since the German Colonies are so sparsely settled—partly because her bureaucratic methods discourage immigration, and partly because she has no difficulty in absorbing her surplus population at home—this argument does not apply here. Closely linked with this is the native question. Personal observation, supported by first-hand [Pg 11] information, serves to show that German treatment of indigenous populations is just what might be expected. To the Englishman, discipline implies leadership—to the German, the mere forcing of will, without consideration for their feelings or personal interests, on subordinates. It serves to crush out individuality and self-respect. It is the discipline of "push." Those who have travelled in Germany will have noticed how this spirit permeates all ranks and classes. That its application becomes more intense in dealing with inferior races, where the restraints of civilisation do not exist, will surprise no one. In the Pacific Islands, as in their African Colonies, the same tale is told. Their native population would rejoice to exchange German for British rule.

If, then, we are to save the next generation from a second great European upheaval, and if we desire to emancipate those native races at present under German control from a system of harsh and selfish exploitation, Germany in Europe must, by the elimination of provinces detached from neighbouring states by previous wars of aggression, be deprived of the power she has so notoriously abused, and if we are to do our obvious duty by the native races, her Colonies must pass to other hands.

A. St. H. GIBBONS.

25th December, 1914.

"The Partition of Africa." J. Scott Keltie.

"Modern Germany." J. Ellis Barker.

"Stanford's Compendium of Geography." A. H. Keane.

"British and German East Africa." H. Brode.

"A Footnote to History." R. L. Stevenson.

"In Near New Guinea." Henry Newton.

"China." E. H. Parker.

"Encyclopaedia Brittanica."

"The Journal of the African Society."

"United Empire"—the Journal of the Royal Colonial Institute.

"Haydn's Dictionary of Dates."

"Samoan Consular Reports."

"Blue Books on Affairs of Samoa."

The "Daily Telegraph."

"Germany and the Next War." General von Bernhardi.

| Page | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| GERMANY AND HER COLONIAL EXPANSION |

17 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| SOUTH WEST AFRICA |

36 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| EAST AFRICA |

84 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| TOGOLAND AND KAMERUN |

109 |

| CHAPTER V | |

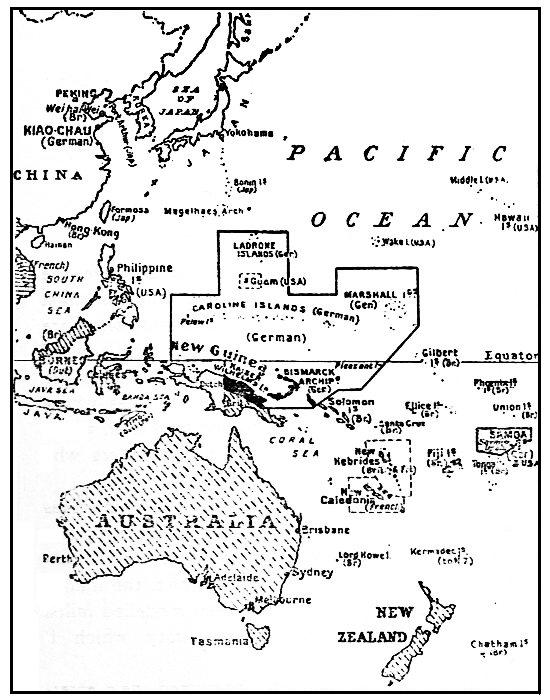

| THE PACIFIC ISLANDS |

124 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| KIAU-CHAU |

172 |

GERMANY'S VANISHING

COLONIES

The German Empire of to-day may best be described as an enlarged and aggrandised Prussia; its people imbued with Prussian ideals and drawing their aspirations from the fountain of Prussia.

In the Confederation of the German States as constituted in 1814, Prussia, under the Hohenzollern Dynasty, was always the turbulent and disturbing element, by methods peculiarly Prussian, working towards a unity of the German states—a comity of nations welded into one under the hegemony of Prussia.

It was not long before Prussian domination became irksome, and her provocative and arrogant attitude created a war with Denmark in 1864 and with Austria in 1866—the latter, a struggle between Hohenzollern and Hapsburg, culminating in the complete discomfiture of Austria.

The war with Denmark gave Germany the harbour of Kiel, together with the million inhabitants of Schleswig-Holstein, and Prussia emerged from the struggle with Austria the leading Power in the new North German Confederation.

Since then the salt of Prussian militarism has been ploughed into the fertile German fields which produced some of the master-minds in the worlds of Thought, Philosophy and Literature.

In accord with true Prussian methods France was forced into a declaration of war in 1870, with the result that the German octopus settled its tentacles upon the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, an area of 5,605 square miles, with 1,500,000 inhabitants.

A new phase of Empire was then created, and the Germany of to-day was constituted as practically a new nation under the rule of William of Hohenzollern, who was elected the "Deutscher Kaiser," or German Emperor, at Versailles on 18th January, 1871.

Prince Otto von Bismarck became the first Chancellor of the new German Empire, and in his hands the fortunes of the House of Hohenzollern prospered, as he set himself to his fixed and single-minded purpose—that was, to elevate Prussia to the foremost place amongst the continental Powers.

Bismarck's policy was directed towards extension, but it was extension of Prussia (or Germany) in Europe and the consolidation of the portions [Pg 19] added to the German Empire. In 1871 he declared "Germany does not want Colonies." He refused to embark upon dazzling adventures in which the risk stirred the imagination, and when an agitation arose in favour of making Germany a sea Power, he confronted it with the words of Frederick the Great: "All far-off acquisitions are a burden to the State." This view he held until the last decade of his career.

Bismarck looked forward, however, to the germanisation of the Low Countries, the absorption of which Cecil Rhodes declared to the German Emperor he believed to be the destiny of Germany.

The spirit of Prussia was even instilled into Austria, and Prussian example was emulated by the House of Hapsburg.

As Prussia set herself to the repression of Danish nationality in Schleswig-Holstein and of French in Alsace-Lorraine, so Austria adopted a policy of eradicating national traits in Hungary.

The national unity aimed at by Bismarck having been established, Germany continued to thrive and grow during the peaceful years following 1871; and the development of the trade of this infant amongst nations is a world's phenomenon.

Yet as with Prussia in the past, so with the greater Germany of to-day, history is a tale of one persistent struggle for possessions.

As is natural during times of peace, the population of Germany increased at an enormous rate, [Pg 20] growing from 35,500,000 in 1850 to 66,000,000 in 1912—an average of about 615,000 per annum—while the present increase is roughly 900,000 per annum.

Between the years 1881 and 1890 German emigration amounted to 130,000 annually; but it was only 18,500 in 1913, and this was more than counterbalanced by immigration from Austria, Russia, and Italy.

Over-population soon became a pressing question, and the obvious remedy was expansion of frontiers or new territories for the accommodation of the surplus.

German policy in a very few years became directed towards extension of territories, for it was apparent that emigration to foreign countries and dependencies only strengthened other nations.

An outlet for the surplus population was required; but in view of the need for men to feed the military machine which had founded the German Empire and upon which its strength depended, it was clear that emigration to foreign countries and dependencies was an inexpedient measure of relief, as it would be applied at the expense of the mother country.

In the year 1882 the German Colonisation Society was started, with the object of acquiring Colonies oversea and the establishment of a navy and mercantile marine to form the link binding the isolated territories to the motherland.

The society was formed by merchants and traders with the end in view of extending trade; but to the militarist section the idea of Imperial expansion presented itself, and to that party the Colonies appealed rather from a strategical than a commercial standpoint.

The society received enthusiastic support, and, indeed, all Germany began to look to Colonies which were to be purely German; and with this enlarged horizon, policy settled down to the acquisition of oversea territory, the ambition being naturally accompanied by an aspiration towards a powerful navy, necessary, ostensibly, to keep communications open.

The German Emperor held very determined ideas on the subject of expansion, but the Chancellor, Bismarck, altered his views only so far as to approve of the founding of Trade Colonies under Imperial Protection.

Bismarck was loth to weaken his military machine by the emigration of men; and the German ideal of colonisation was not, therefore, a policy of settlement but one of commercial exploitation; inasmuch as Germany's aim was to develop home industries in order to keep in employment at home the men who formed the material of her armour.

Germans were required to remain Germans; and this object it was hoped to attain by settlements in German Colonies, where compact centres of [Pg 22] German kultur could be established to teach the art of order to the remaining peopled kingdoms.

The German view being that the British oversea Empire was acquired "by treachery, violence and fomenting strife," one cannot imagine, especially with her Prussian traditions, a violent disturbance of the "good German conscience" in contemplating means of attaining an object.

In the first Prussian Parliament Bismarck thundered out "Let all questions to the King's Ministers be answered by a roll of drums," and, in sneering at the ballot as "a mere dice-box," he declared: "It is not by speechifying and majorities that the great questions of the day will have to be decided, but by blood and iron."

Prussia had fought for and won her predominance; her greatness was acquired by the sword; and the Bismarck cult has prevailed in that no other means of expansion and nationalisation than by conquest presents itself to the German mind. All negotiations with foreign nations, therefore, have been conducted to the accompaniment of the rattle of the sword in the scabbard.

Speaking of Colonies in his recent bombastic book, General von Bernhardi said: "The great Elector laid the foundation of Prussia's power by successful and deliberately planned wars"; and in justifying the right to make war he says: "It may be that a growing people cannot win Colonies from uncivilised races, and yet the State wishes [Pg 23] to retain the surplus population which the mother country can no longer feed. Then the only course left is to acquire the necessary territory by war."

Germany now proposed to tread the same path as England, but she had arrived late in the day and the methods whereby she purposed making up for lost time were not the methods whereby England had established herself.

Behind German colonisation lies no record of great accomplishments inspired by lofty ideals and high aspirations, carried into effect by noble self-sacrifice on the part of her sons; the history conjures up no pageant of romantic emprise nor vista of perilous undertakings in unexplored parts of the globe by the spirits of daring and adventure; it holds no pulse-stirring stories of the blazing of new trails; and scattered over its pages we do not find imprints of the steps of pioneers of true civilisation, nor are its leaves earmarked with splendid memories.

Where England gave of the best of her manhood to establish in daughter states in the four quarters of the globe her ideals of freedom, justice, and fair commerce—that manhood whose inspiration and incentive was their country's honour, but whose guerdon was in many a case a lonely grave or a more imposing monument in the "sun-washed spaces"—the ambassadors of German kultur followed upon a beaten track to seize at the opportune moment the material benefit of the crop where [Pg 24] the others had ploughed with the expenditure of their physical energy, sown with the seeds of their intellect, and fertilised with their blood.

Casting about between 1882 and 1884 for territory over which to hoist her flag, Germany found that nearly the whole of the world was occupied; and direct action of conquest not being expedient, Germans were busy seeking to accomplish their aims by secret methods of intrigue, always accompanied by deprecation of the infringement of the vested rights of others.

Active steps for the acquisition of territory began to be taken in 1884.

Under pretext of being interested in the suppression of the slave trade, Germany concerned herself in the affairs of Zanzibar, long subject to the influence of the Portuguese and British; but Germany later abandoned her ambitions in the island on the cession of Heligoland.

Africa was the one continent which had not been partitioned, and Germany's quest of territory brought about the "scramble for Africa."

Germany had annexed portions of the west coast (Togoland and Kamerun), and the vacillating policy of the British Government during 1882-1883 enabled the Germans to annex an enormous tract of territory north of the Orange River, which became known as German South West Africa.

Altogether the German Colonies in Africa [Pg 25] acquired in 1884 amounted to over 1,000,000 square miles.

By what is known as the "Caprivi Treaty" of the 1st July, 1890, Great Britain and Germany agreed as to their respective "spheres of influence" in Africa.

Great Britain assumed protection over the Island of Zanzibar, and ceded to Germany in exchange the Island of Heligoland.

This exchange was regarded in Germany generally as a most disadvantageous one; but the possession of Heligoland as a fortress was of inestimable value to Germany—making possible the Borkum-Wilhelmshaven-Heligoland-Brunsbüttel naval position, and the German militarist section craved it in order to forestall France.

The territory of the Sultan of Zanzibar on the mainland of Africa was ceded to Germany, with the harbour of Dar-es-Salaam; and the boundaries were so delimited as to include in German East Africa the mountain of Kilima 'Njaro, the German Emperor being supposed to have expressed a wish to possess the highest mountain in Africa as a mere matter of sentiment.

The Caprivi Treaty also defined the boundaries of South West Africa.

In 1884 Germany had also busied herself in the Pacific, and had hoisted her flag on several islands as well as in North New Guinea, where the Australasian Colonies had established settlements and [Pg 26] vainly urged annexation on the British Government.

In 1885 the sum of 180,000 marks was voted by the Reichstag "for the protection" of these new German Colonies.

The opening of 1891 saw Germany with ample territory oversea to accommodate surplus population; while we, secure in our own strength, with amused tolerance, allowed her to climb to "her place in the sun."

It was not the intention of Germany, however, to use the Colonies as dumping grounds, nor to encourage a policy of emigration—but rather to exploit them as supports for home industry.

Many German industries depend upon foreign countries for the import of a continual supply of raw material which cannot be produced in Germany; while part of their necessaries are even obtained from abroad. They also depend to a considerable extent upon foreign countries for the sale of manufactures.

Their prosperity depends upon import and export trade; for while the home industries provide work for masses of the population, all the products cannot be consumed at home and markets have to be found elsewhere if employment is to continue.

It can never be said to be an economic interest to encourage the establishment of industries in Colonies—at least not manufactories of articles made at home.

The establishment of such may be of interest to provide work for those who emigrate; but from the point of view of countries like Germany, whose existence depends on keeping their men at home, it is far preferable to develop every possible industry at home, and retain the Colonies only as markets and producers of raw material.

This Germany proceeded to do. Developing Colonial trade, she extended her home industries. During eight years her Colonial trade rose from scarcely £5,000,000 to £12,000,000, and the effect of the acquisition of Colonies upon her home industries is marked in the fact that she employed in those industries 11,300,000 men in 1907 as against 6,400,000 in 1882.

Germany, moreover, protects even her agriculture against the competition of her own Colonies—shutting out their meat and their grain.

Germany's conception of the idea of Colonies, therefore, was to build up overseas a new Germany composed of daughter states, which would remain essentially German and be the means of keeping her men at home in remunerative employment by providing raw material for the development of her industries.

A continental nation, surrounded by powerful neighbours, it seemed in her case a suicidal policy to scatter her population abroad; and therefore she exploited her Colonies in such a way as to help her to concentrate her people at home, where she [Pg 28] required men in time of peace for economic development and in time of war for defence—and offence.

As a natural sequence to the responsibility of oversea dominions, it becomes a question of life and death to keep open the oversea commerce protected by a powerful navy; and this point was strongly urged by the National Party which, advocating colonisation, arose in Germany in 1892.

But with the growth of Germany's oversea trade and her navy, a new and splendid vista unfolded itself—no less than Germany, from her place in the sun, mistress of the world.

To quote von Bernhardi: "The German nation, from the standpoint of its importance to civilisation, is fully entitled not only to demand a place in the sun, but to aspire to an adequate share in the sovereignty of the world far beyond the limits of its present sphere of influence."

Von Treitschke, the neurotic German historian and poet, again "incessantly points his nation towards the war with England, to the destruction of England's supremacy at sea as the means by which Germany is to burst into that path of glory and of world dominion."[A]

"Treitschke dreamed of a greater Germany to come into being after England had been crushed on the sea."[B]

To obtain their object no other means presented itself than the Prussian militarist method.

Bismarck's object—the goal towards which he strove, to so amply secure the position in Europe that it could never be questioned—seemed to have been attained by the machine of militarism, the huge army created and kept in being by national self-sacrifice. So to obtain what was now aimed at, the instrument was to be an invincible fleet which would in defiance of everyone keep sea communications open.

As early as 1896 the "world Power" idea had evolved, and at the celebration in that year of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the foundation of the German Empire, the Emperor termed it a "world Empire."

On the question of the rights of others the German Emperor was at all events satisfied, for he announced to the German Socialists: "We Hohenzollerns take our crown from God alone, and to God alone we are responsible," which leaves nothing more to be said on that point.

To German minds the domination of the world was a very real ambition and quite in accord with the best Prussian traditions.

In 1905 the German Emperor visited Tangier to impress upon a cynical brother Emperor the right to a place in Moroccan affairs; while in 1911 German diplomacy asserted that Germany was anxious to preserve the independence and integrity [Pg 30] of Morocco because of her important interests in the country. As a matter of fact, German trade had steadily lost ground in Morocco and "in 1909 was exactly equal to 1/1500th or one-fifteenth part of one single per cent of her whole foreign trade."[C]

Anent the Agadir crisis in 1911, Von Bernhardi naively admits that it was "only the fear of the intervention of England that deterred us from claiming a sphere of interests of our own in Morocco."

The "sphere of interests" in Morocco consisted in coveting Agadir, the best harbour on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, which would have been of enormous importance to Germany and her Colonies because ordinarily the German fleet would be tied to the North Sea for want of coaling stations.

During Great Britain's time of stress with the South African Republics, in the same way Baron Marshall von Bieberstein declared officially that "the continued independence of the Boer Republics was a German interest."

The interest of Germany, apart from the undoubted hope of making the Republics German Colonies, it might simply be remarked, was that Germany had in contemplation the construction of a railway line from Pretoria to Santa Lucia Bay on the east coast, 800 miles nearer Europe than the port of Cape Town.

German history holds no record of the integrity or independence of her neighbours being either of German interest or concern, and her attitude is in accord with her principle of concealing her real intention by adopting a spirit of deprecation.

This is amply exemplified in the German Emperor's letter to Lord Tweedmouth of 14th February, 1908, stigmatising as "nonsensical and untrue" the idea that the German fleet was being built for any other purpose "than her needs in relation with her rapidly growing trade."

The real obstacle to realisation of the great German dream was British naval supremacy; and all German thought and energy was devoted to the construction of a navy strong enough to challenge that supremacy. When she could do that it was within the bounds of possibility that Germany would indeed be the world Power.

Roughly, the German Colonial Empire is five times as big as Germany, with a population of about 14,000,000 natives; and the question of German Colonial policy is a question of native policy.

It is in Germany's interest that the natives should be as numerous as possible, for it is their labour, intelligence, and industry that makes the Colonial Empire useful and necessary to Germany.

Individual settlers are not encouraged to emigrate, but the plantations, ranches, etc., whence Germany drew her supplies of raw material such as cotton, rubber, wool, etc., are developed by [Pg 32] chartered companies and trading firms, and the so-called settlers are the managers of these.

Independent German farmers in her Colonies are few and far between, and the settlements which were to be centres of German kultur have not eventuated. A new Germany has not been created oversea.

There was, moreover, no room in German Colonial expansion for individualism, which has proved such a strength to England but was suppressed in Germany. The individual German is not given scope but subordinated to a system.

The truth seems to be that Germany had not got the class of men she required for her scheme of Colonial development—or exploitation seems the better word.

Germany's requirements were lands for growing raw material by native labour, and markets from which she could not be excluded—and she thought she had found them in her Colonies.

The Colonies cried out for European enterprise and European capital, but they did not want individual settlers.

Under British rule the German has proved a most desirable Colonist, but he has never thriven under his own Colonial administration.

He is by nature extremely assimilative, and in our Colonies he prospers, not only competing with but outstripping the British trader owing to the employment of undercutting methods which do not [Pg 33] so readily occur to the British mind, hampered as it usually is by a sense of fair play.

In the eastern province of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope, the members of the German Legion who settled after disbandment about King William's Town, Hanover, Stutterheim, etc., have developed into prosperous farmers and merchants.

A sandy waste in the neighbourhood of Cape Town, once thought to be worthless, was subdivided and taken up almost entirely by Germans, and they have turned the land into one of the most productive portions of the Cape Peninsula.

In America the German immigrants have readily assimilated, though in Brazil they have formed separate centres.

In the German Colonies a set-back to development has been the fact that they have never realised the importance of respecting local manners and customs, but the home machinery has been applied in every particular to conditions wholly dissimilar and unsuitable.

In South West Africa, for instance, Dr Bönn of Munich says they "solved the native problem by smashing tribal life."

Being trained and accustomed to obey, moreover, the German cannot act without orders, and lacks initiative and therefore administrative ability.

Compulsory military service has been instituted, and the German Colonial administration is cordially [Pg 34] detested except where perhaps it favours ill-treatment and oppression of natives.

Where the British have evolved a system of government which is a comity of commonwealths within a monarchy, and hold their dependencies by the sense of honour and appreciation, to which the attitude of South Africa bears splendid witness, the German's grip was by the claws of militarism and terrorism.

Under the circumstances it is perhaps not surprising that the Germans should fall into the error that the British dependencies would embrace an opportunity of "throwing off the British yoke"; and the assumed disloyalty of British Colonies, with the further assumption, widely distributed, that various peoples under the British flag were capable of being tampered with easily, may well have been one of the most cogent theories leading the German Emperor and his advisers to their fateful decision.

With the extraordinary aptitude of the Germans for intrigue, perhaps the war Lords were not altogether foolish in their conclusions.

There was a chance of seduction, especially with native races in Africa, but it was a very small chance, and, like many another well-laid scheme, this one failed because its authors did not understand the material which was to be used to work it.

It failed in Africa because the African is more than the beast of burden the German Colonists [Pg 35] schooled and deluded themselves into thinking. They did not understand the native; and, in a word, the native hates the German, especially the officials.

Their methods of colonisation have good points in matter of detail, routine work, etc.; but if colonisation be regarded as something more than the exploitation of a subject race and the passive holding of its territory, they must be written down a failure, for the extraordinary efficiency of the administrative machinery falls far short of compensating for the rottenness of the policy behind it.

A nation in whom a much-vaunted kultur has produced an ideal of national life whose highest expression is the atmosphere of a penal settlement, is foredoomed to failure as a coloniser.

Ever since her acquisition of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope, vitally important to her in view of her interests in the East, Great Britain had been unquestionably the supreme Power in the south of the African Continent.

With the passing of the Dutch East India Company, Holland had ceased to be a South African Power; while the Portuguese had lost their status. The latter in reality only held an area along the coast of her possessions, a great proportion of the interior, which undoubtedly had once been beneficially occupied by Portuguese, having reverted to savagedom.

The southern point of Portuguese South East Africa extended to and included Delagoa Bay and Lourenço Marquez, while the southern boundary of their western Colony was about the 22° S.

From the days of its earliest history the Cape Colony was subject to attacks by natives, and the constant raids by hordes of Kafirs caused the Colony to extend its borders and absorb and settle the Hinterland.

THE GERMAN COLONIES IN AFRICA, 1914.

THE GERMAN COLONIES IN AFRICA, 1914.Up to 1883 the natural course of beneficial occupation and development had been towards the east and north-east borders, over the more fertile and naturally resourceful portions of the country, rather than west and north-west, where a comparatively arid zone intervened.

Towards the Orange and Vaal Rivers the hardiest race of pioneers the world has ever seen, the "Voor-trekking" Boers, pressed onwards to escape from subjection to any form of government excepting their own patriarchal control. Their story hardly comes within the scope of this modest work; but it is indissolubly connected with the making of South Africa, and a brief sketch of their history may be permissible.

The exodus of the Boers, who were composed of farmers of not only Dutch but French and English origin, commenced with the Great Trek of 1836, and they spread out ever seeking freedom from restraint. They came into collision with the Zulus under Dingaan, by whom a number of them were treacherously massacred, but whom they finally severely defeated and Dingaan fled.

Dissensions arose amongst the Boers shortly after, and a number trekked on and established a separate settlement, with Potchefstroom as capital. Those who remained occupied Natal and established a Republic.

Here, however, they did not find peace, for Sir George Napier, in command of the British forces at the Cape, dispatched a contingent to drive them out. This contingent the Boers nearly annihilated.

A settler, Dick King, then made his memorable ride from Durban to Grahamstown, covering the distance of 375 miles in nine days, and reinforcements were sent up.

Natal was, in 1843, declared to be a British Colony, with the result that a fresh exodus of Boers occurred across the Drakensberg Mountains into Griqualand.

For forty years the Boers wandered, but wherever they tried to settle they were pressed on—being continually told that they could not shake off their allegiance, although no step was taken to reclaim them or the country they won.

So far from receiving protection from the Cape Government, the latter even armed the Griquas against the Boers, and sent a military force to the assistance of the natives. And so they were harried until they were allowed to establish their Republics of the Transvaal and Free State, until overtaken by the destiny which Providence had marked out for them.

In 1881 an attempt was made by Great Britain to annex the Transvaal, but after General Colley's defeat and death at Majuba the independence of the Transvaal was acknowledged under British suzerainty.

The western border of the Transvaal Republic marched on Bechuanaland and the Kalahari Desert, and in 1882 the Transvaal completed a convention with the Portuguese Government under which the former was granted a concession to build a railway from the capital, Pretoria, to Delagoa Bay on the east coast.

The delimited boundary of the Cape Colony was the Orange River, but as early as 1793 a Dutch expedition from the Cape took possession of Walfisch Bay, Angra Pequena, as well as Possession, Ichaboe, and other islands on the south-west coast in the name of the Dutch East India Company, while Namaqualand and Damaraland had been traversed from end to end by British and Dutch traders and explorers.

British statesmen, however, neglected the south-west, though the islands were annexed at different times between 1861 and 1867, and Walfisch Bay in 1878. In 1874 the islands were incorporated in the Cape Colony.

The mainland on the south-west, however, remained an open field as far as actual occupation went, in spite of its being tacitly acknowledged a British "sphere of influence."

Until the "scramble for Africa" no one would have regarded with anything but ridicule the idea that an enormous tract of country, comprising Great Namaqualand and Damaraland, would have been lost to Great Britain; yet British statesmen at home, [Pg 42] feeling secure in the country's position, refused to encourage anything but a policy of gradual absorption.

In 1867 the Home Government was strongly urged by the Government of the Cape to annex Great Namaqualand and Damaraland, but declined to undertake the responsibility.

In the following year the residents of the territory, including numerous German missionaries, urged that the country might be declared British and be subject to British administration; but the proposal was met with disfavour.

In the year 1877 that great-minded Imperialist, Sir Bartle Frere, then Governor of the Cape of Good Hope, advised by the Executive Council at the Cape, made a strong recommendation that as a first step an Order in Council should be passed, empowering the Cape Parliament to legislate for the purpose of annexing the coast up to the Portuguese boundary; and that in the meanwhile no time should be lost in hoisting the British flag at Walfisch Bay. This latter step was assented to, and it was shortly afterwards carried into effect; but Sir Bartle Frere's larger proposals were negatived.

Sir Bartle Frere subsequently renewed his representations on the subject, but the Imperial Government continued of opinion that no action should be taken.[D]

The British Imperial Government was satisfied that there could be no possible danger in delay, and were disturbed at the unsettled state of the native territories of the Cape Colony and the recurrence of native disturbances which have been a prevailing element in the existence of the Colony.

The Imperial Government finally decided that it was unnecessary to extend their possessions beyond the then boundaries, that the Orange River should be maintained as the north-western boundary of the Cape Colony, and that the Government would give no encouragement to schemes for the extension of British jurisdiction over Great Namaqualand and Damaraland.

Up to 1883 the only assent to petitions from the Cape Government, from residents in Great Namaqualand and Damaraland, and from the natives of those territories, was for the annexation of the islands off the coast, and of Walfisch Bay and a very small portion of the country immediately surrounding it.

The danger of Germany stepping in was never disturbing to the minds of the British statesmen, and they were merely concerned with weighing the advantages of embracing the occasion.

German diplomacy had, however, been at work in its insidious way; and although active operations under Bismarck's policy of forming "Trade Colonies" were not undertaken by the German [Pg 44] Government until well into 1884, the promoters and originators of the German Colonisation Society had been busy ever since the first conception of the Colonial idea in Germany.

During the years preceding 1884, indeed, representatives of the Bremen and Hamburg merchants had made many not unsuccessful efforts to worm themselves into the trading centres in Southern Africa.

Ambassadors of German commerce set out as pioneers of the new movement, and as early as August, 1883, the Standard newspaper published a communication from its special correspondent in Berlin—headed "The First German Colony"—reporting that a Bremen firm had "acquired" the Bay of Angra Pequena (Luderitzbucht) on the south-west coast of Africa.

The article proceeds that "the German Press, which was disappointed by the Reichstag last year (re the Samoa Bill), expresses great satisfaction at the consent of the German Government to protect the infant Colony and to allow the German flag to be hoisted over it. The semi-official Post declares that this is the most practicable kind of colonisation, because it avoids international difficulties. In spite of the statement ... that the German Government avoids giving any encouragement to immigration, the Post is convinced that if Germans will promote the increase of German manufacturing industry by founding commercial Colonies, they [Pg 45] will not lack the powerful protection of the Imperial Government."

There the whole of Bismarck's ex-territorial policy lies in a nutshell: the continued expansion of Germany from within by means of trade with purely German dominions.

Beyond this the German Government expressed no intention of actually annexing territory, though it was a straw which showed very clearly the direction in which the wind set.

It was an inexpedient policy for the Government to proceed to declaring Protectorates over areas not in actual occupation by other Powers yet coming within their "spheres of influence," and the subterfuge resorted to was the establishment of trade centres by merchants who would claim the protection of the German flag; albeit it could not be seriously argued that the mere foundation of a trading station could constitute territorial acquisition in any part of the world where Germany as a Power had not the least claim.

For many years there had in Germany been advocates of colonisation schemes with a considerably wider horizon, who had formulated ideas of expansion and pressed their views upon the German Government and public. Foremost amongst these was Herr Ernst von Weber, and the enunciation of his higher ambitions for his country, in a remarkable article published in 1879, not only attracted considerable attention in South Africa but induced [Pg 46] Sir Bartle Frere again to draw the attention of the Home Government to the avouched plan for a German Colony in South Africa.

Herr von Weber in his article pointed to the attractive prospect and noble ambition by which Englishmen might be inspired to found a new Empire in the African continent, "possibly more valuable and more brilliant than even the Indian Empire."

Von Weber argued that it was the duty of Germany to protest against steps taken by England to realise this ambition; urging in support that Germans had a peculiar interest in the "Boer" territories—"for here dwell a splendid race of people nearly allied to us (Germans)."

After going into the history of the Boers, the writer of the article states quite seriously that the Transvaal Boers had "the most earnest longing that the German Empire, which they properly regard as their parent and mother country, should take them under its protection."

As a matter of fact, except in Government circles in the coterie of continental intriguers who surrounded and misled Paul Kruger, the German is barely tolerated by the Boers, and vervluchste Deutscher (cursed German) is as common a descriptive as verdomde Rooinek (damned Englishman).[E]

In the first place, to the Boers every German is a Jew—a gentleman, in his mind, associated with a watch with defective parts or a "last year's ready reckoner."

Next, the Boer, while proud of his ancestry, strongly disclaims any loyalty to a European Power; and although a Dutch dialect is in almost universal use, he would indignantly repudiate a suggestion that he is bound by any ties to Holland, even after he has been fully persuaded of the actual existence of that country.

The Boer trekkers, besides those of Dutch origin, included the descendants of many noble French families, and their numbers were supplemented by English immigrants who were sent out to the eastern province of the Cape Colony in 1820. Many of these trekked with the Boers owing to dissatisfaction at being denied political and civil rights; and of the original 3053 immigrants who landed in 1820, only 438 remained a few years later, on their original grants in the Cape Colony.

While the Boers protested and fought against annexation by great Britain, it was merely because of repugnance to restraint and certainly not out of any love for Germany.

After expatiating on the richness of the mineral resources of the Transvaal, von Weber points to the possibilities of the country if Delagoa Bay were acquired.

In spite of claiming the Boers as kindred, however, [Pg 48] he shows the cloven hoof by stating that "a constant mass immigration of Germans would gradually bring about a decided numerical preponderance of Germans over the Dutch population, and of itself would by degrees effect the germanisation of the country in a peaceful manner."

He goes on to recommend that Germany ought "at any price," in order to forestall England, to get possession of points on both the west and east coasts of Africa, where factories could be established, branches of which, properly fortified, could be gradually pushed farther and farther inland and so by degrees form a wide network of German settlements.

That these views were not held by Herr von Weber alone in Germany must have been apparent to our Foreign and Colonial Offices, but the only steps taken were to ask the British ambassador in Berlin for a report; and this, when received, assured the Government that the plan had no prospect of success, because the German Government felt more the want of soldiers than of Colonies, and consequently discouraged emigration—while the German Government's disinclination to acquire distant dependencies had been marked in the rejection of the Samoa Bill.

The possibility of a reversal of feeling did not occur to anyone apparently, and the British Government was therefore quite satisfied that "the plan had no prospect of success"; and having intimated [Pg 49] the same to Sir Bartle Frere, abandoned interest in the matter.

To the Prussian militarist section in Germany Ernst von Weber's exhortation irresistibly appealed. A glance at the map of South Africa will show how feasible it was for Germany not only to curtail the expansion of British territory from the south, but to secure the dominion of the greater part of the continent for Germany.

It was a great ideal and came near to consummation by insidious working of German Government agents, bountifully assisted in their object by the vacillation and indifference of the British Colonial and Foreign Offices.

In the south-west was a huge area of which no actual annexation had been proclaimed, yet to the mind of our statesmen amply secured by being understood to be within the "sphere of British influence." Between it and the Transvaal Republic lay another unprotected area stretching across the Kalahari so-called "desert" and including Bechuanaland, the happy hunting-ground of missionaries and Matabele raiders. South-east of the Transvaal, stretching to the coast, was another unoccupied region comprising Tongaland and part of Zululand, with an excellent harbour on the east coast at St Lucia Bay.

Give any Power Great Namaqualand and Damaraland on the west coast, add Bechuanaland in the interior and a working agreement with the [Pg 50] Transvaal Republic with access to the east coast at St Lucia Bay, then the Cape Colony was shut in by very circumscribed borders for ever from her Hinterland; while a dream of "Africa all Red" was smothered in its genesis, and its record filed away for future reference in the archives of the might have been.

But a belt across the southern portion of the continent did not comprise the sum-total of the Prussian ambition. There was an enormous and fabulously rich extent of country stretching up to and beyond the Zambezi, occupied only by marauding savages under the rule of Lo Bengula, King of the Amandebele—and now known as Rhodesia.

With a distinct vision of the prize offering, the German set out with the mailed fist wrapped in cotton wool to stalk his prey delicately.

In 1883 while German traders were busy establishing a footing in Great Namaqualand and Damaraland, diplomacy and intrigue had been at work in the Transvaal. The Boer Government had concluded an agreement with the Portuguese whereby they obtained an outlet to the east coast by a railway to Delagoa Bay, and the Boers had begun to occupy portions of Bechuanaland, separating the Transvaal and Namaqualand.

Boer Republics were proclaimed over the territories of several Bechuana chiefs, and overtures were made by German emissaries from the Transvaal to Lo Bengula for a concession over the territory under his sway.

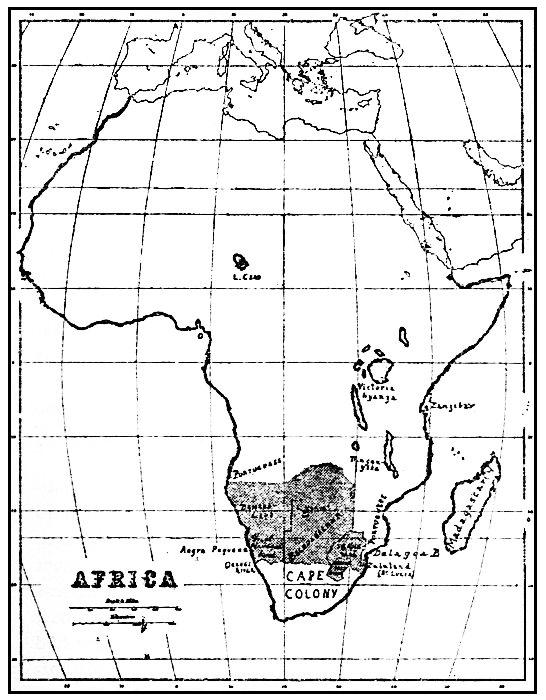

SOUTH AFRICA IN 1883.

SOUTH AFRICA IN 1883.Tongaland and a portion of the Zululand coast, including St Lucia Bay, was under the subjection of Dinizulu, who had succeeded Cetywayo as King of Zululand, and with him negotiations were entered into, the ultimate end of which was to be the cession to Germany (or the Transvaal) of a portion of the sea-board.

The British Government can hardly really be blamed for not pursuing in 1883 a vigorous policy of annexation in Southern Africa, for in 1879 there had been general native disturbances—including a costly war with the Zulus, with its memorable disaster to the British arms at Isandhlwana and the deplorable death of Prince Victor Napoleon. In 1881 we were defeated by the Boers at Laings Nek and Majuba, the little war ending with a retirement quite the reverse of graceful; in 1882 Egypt was in a foment, and although Sir Garnet Wolseley destroyed Ahmed Arabi at Tel-el-Kebir, the Sudan was still overrun by frenzied fanatics.

The dilatoriness of the Imperial Government, however, is inexcusable in view of the importance of the issue at stake, which was the overthrow of British supremacy in South Africa in favour of Germany.

Fortunately for us, there were at the Cape imperially minded statesmen who were fully alive to the danger threatening Great Britain: Sir Bartle [Pg 54] Frere, Cecil Rhodes, Sir Thomas Upington, and John X. Merriman; and these continually pressed their views upon the Home Government, while Rhodes, who had formulated his own ideas as to the destiny of the sub-continent, set himself to employ his bounteous talents of mental and physical energy to the due accomplishment of a purpose which he made his life's aim.

Fortunately he had at his private command the financial resources indispensable to the consummation of his ideals; for if he had had to rely upon the Home Government for that support, his ambition stood little hope of realisation.

The German hope of obtaining sway over Bechuanaland through the Boers was frustrated by vigorous action on the part of the Cape statesmen. Their protests, and especially the individual efforts of Rhodes, stirred the Home Government into saving for the Empire the territory which the freebooters from the Transvaal had seized upon in the name of their Republic.

Rhodes personally, on behalf of the Cape Government, conducted negotiations with the Boers, but it was not until 1885 that a successful issue was arrived at after a show of force by the Home Government in the expedition of Sir Charles Warren.

The danger of the Cape Colony being cut off from the north through Bechuanaland was obviated, but a large field for German enterprise still lay open.

Their attempts to acquire a footing in Matabeleland were frustrated, and the delegates who set out from the Transvaal in search of a concession from Lo Bengula were unsuccessful in their mission to secure for Germany sway over the countries that now comprise Rhodesia.

For decades British private enterprise had been busy on the coast of Great Namaqualand and Damaraland; in fact in 1863 a British firm (De Pass, Spence & Co.) had purchased from the native chiefs a large tract round about Angra Pequena, and worked the huge deposits of guano on the Ichaboe group of islands, some of which are less than a mile off the mainland.

Disputes were constant up to 1884 between British and German traders; continuous appeals were made for British annexation of the territory from the Orange River to the Portuguese border, but the Government could not be induced to do anything more towards acceding to Sir Bartle Frere's urgent representations than to declare Walfisch Bay, with some fifteen miles around it, to be British territory.

In 1882 a German, Herr Luderitz, the representative in South Africa of the Hamburg and Bremen merchants who pulled the strings of the Government through the German Colonisation Society, established a trading station at Angra Pequena and commenced, in accordance with the preconceived plan of "conquest," to extend the operations of [Pg 56] his business inland by founding trade stations at suitable centres.

The British traders soon began to make representations to the Cape Government owing to Luderitz exercising rights of proprietorship over a large portion of territory which he claimed to own by purchase, and to his levying import duty charges upon goods landed by other traders.

Another cause of complaint was that Luderitz was importing large quantities of arms and ammunition and supplying them to the natives by way of barter.

The German wedge having been insidiously inserted into South West Africa, the propitious moment seemed to have arrived in 1884 for Germany to acquire territorial possession of South West Africa. Representations were accordingly made by the German to the British Government, pointing out that German subjects had substantial interests in and about Angra Pequena in need of protection, and inquiring whether the British were prepared to extend protection to the German industries and subjects north of the Orange River, which British statesmen seemed to have stubbornly determined should remain the boundary of the Cape Colony.

The Governor of the Cape had, indeed, been clearly and distinctly given to understand that, except as regards Walfisch Bay, the Home Government would lend no encouragement to the establishment [Pg 57] of British jurisdiction in Great Namaqualand and Damaraland north of the Orange River.

Bismarck's application to Lord Granville, therefore, placed the latter in an awkward predicament, inasmuch as he intimated that if Great Britain were not agreeable to providing protection for the lives and properties of German subjects, the German Government would do its best to extend to it the same measure of protection which they gave to their subjects in other remote places.

Bismarck took care, however, to impress upon the British Foreign Office that in any action the German Government might take there was no underlying design to establish a territorial footing in South Africa. He disclaimed any intention other than to obtain protection for the property of German subjects; and this assurance was complacently accepted as a complete reply to the representations of the Cape statesmen.

The Home Government seem, at the same time, to have understood at the beginning of 1884 that the choice lay before them of formally annexing South West Africa from the Orange River north to the Portuguese border, or acquiescing in a German annexation.

With almost criminal procrastination, however, they deferred replying to the German inquiry, deeming it necessary to communicate with the Government of the Cape Colony and invite that Government, in the event of South West Africa [Pg 58] being declared to be under British jurisdiction, to undertake the responsibility and cost of the administration of the territory.

Lord Granville, moreover, temporised by informing Bismarck that the Cape Colonial Government had certain establishments along the south-western coasts, and that he would obtain a report from the Cape, as it was not possible without more precise information to form any opinion as to whether the British authorities would have it in their power to give the protection asked for in case of need.

This answer Bismarck probably expected and welcomed, as it left him free to proceed with his own arrangements, while the British Foreign Office pigeonholed the subject until the matter might be reopened.

In the beginning of 1883, owing to representations from British firms interested in South West Africa as to German activity in that part, the British Foreign Office obtained a report from their Chargé d'Affaires in Berlin, and were again lulled into complaisant inactivity by being assured that the amount of "protection" intended to be afforded by the German Government to Luderitz's "commercial Colony" was precisely what would be granted to any other subject of the Empire who had settled abroad and acquired property.

It would be a mistake, the Foreign Office was notified, to suppose that the German Government had any intention of establishing crown Colonies [Pg 59] or of assuming a Protectorate over a territory acquired by a traveller or explorer.

In September the German inquiries of the Foreign Office assumed a more pertinent nature, and to the uncultured mind would carry an alarming significance.

The British Foreign Office was asked "quite unofficially" and for the private information of the German Government, whether Great Britain claimed suzerainty rights over Angra Pequena and the adjacent territory; and if so, to explain upon what grounds the claim was based.

This necessitated another reference to the Cape of Good Hope; but in the meantime a party of English traders, disgusted at the delay at home in annexing the south-west coast, resolved to take action on their own account, and set off for Angra Pequena with the fixed determination—of which they gave the Government due notice—of expelling the Germans.

Instructions were immediately sent out for a gunboat to proceed to the spot to prevent a collision between the British and Germans, as the whole question of jurisdiction was still the "subject of inquiry."

H.M.S. Boadicea proceeded on instructions to Angra Pequena, and her Commander was able to report, on her return to Simon's Bay on the Cape station, that no collision had taken place.

In November, 1883, the British Foreign Office [Pg 60] intimated to the German Government that a report on South West Africa was in course of preparation, but that while British sovereignty had not been proclaimed excepting over Walfisch Bay and the islands, the Government considered that any claim to sovereignty or jurisdiction by a foreign Power between the Portuguese border and the frontier of the Cape Colony (the Orange River) would infringe Great Britain's legitimate rights.

Early in 1884 the German Government, in a dispatch to the British Foreign Office, pointed out that the fact that British sovereignty had not been proclaimed over South West Africa permitted of doubt as to the legal claim of the British Government, as well as to the practical application of the same; the German Government having clearly in mind the avowal of a fixed intention on the part of the British Government not to extend jurisdiction over the coast territory excepting in so far as Walfisch Bay and the islands were concerned.

The dispatch argued that events had shown that the British Government did not claim sovereignty in the territory, but as a matter of fact the Government had emphatically declined to assume that responsibility.

The German dispatch concluded by asking our Government for a statement of the title upon which any claim for sovereignty over the territory was based, and what provision existed for securing legal protection for German subjects in their commercial [Pg 61] enterprises and property, in order that the German Government might be relieved of the duty of providing direct protection for its subjects in that territory.

Here, again, was a deprecation on the part of Germany of any other ambition than to secure protection for life and property of German subjects.

Lord Derby, Secretary of State for the Colonies, was aware of the possibility of Germany assuming jurisdiction over Angra Pequena in the absence of an assurance that the British Government was prepared to undertake the protection of German subjects; but the British Government shrank from the idea of annexing the territory, and endeavoured to saddle the Cape Government with the responsibility of giving the undertaking asked for by Germany.

The Cape Government was in no position to assume such a responsibility, though they did not hesitate to offer to do so as soon as a cabinet meeting could be called to decide on the matter—but when it was too late.

On the 30th January, 1884, the Cape Government, in a minute signed by John X. Merriman, recommended the annexation to the British Empire of the whole of Great Namaqualand and Damaraland from the Orange River to the Portuguese border, the interests of the Cape Colony being chiefly in the arming of natives by gun-running through the port at Angra Pequena.

Official and private notifications were sent to the British Foreign Offices of the intention of Germany to take over the suzerainty of South West Africa in defiance of Great Britain's claims; but our Government, fondly embracing the idea that Germany had no intention of acquiring the territory but was only solicitous for legal protection of private property, still declined to act until the Cape Government expressed their readiness to accept the responsibility and cost.

On the 24th April, 1884, the day which has recently been described in German publications as "the Birthday of the German Colonial Empire," Bismarck telegraphed to the German Consul at Cape Town as follows:

"According to statements of Mr Luderitz, Colonial authorities doubt as to his acquisitions north of Orange River being entitled to German protection. You will declare officially that he and his establishments are under protection of the Empire."

This meant the annexation to Germany of the whole territory; but communications continued between the Home and the Cape Colonial Governments.

In the Reichstag on the 23rd June, 1884, Bismarck showed his hand for the first time; and on the point of infringement of Great Britain's "legitimate [Pg 63] rights," stated that no such infringement could be pleaded inasmuch as in English official documents the Orange River had repeatedly been declared to be the north-western border of the Cape Colony.

Bismarck further announced that it was the intention of the Government to afford the Empire's protection to any "settlements" similar to that of Luderitz which might be established by Germans. He added in his address to the Reichstag that "if the question were asked what means the Empire had to afford effective protection to German enterprises in distant parts, the first consideration would be the influence of the Empire and the wish and interests of other Powers to remain in friendly relations with it."

There was nothing left but for our Government to bow at the triumph of superior diplomacy, and the position was accepted with a good grace—Lord Granville declaring that in view of the definitions which had been publicly given by the British Government of the limits of Cape Colony, the claim of the German Government could not be contested, and that the British Government was therefore prepared to recognise the rights of the Germans.

There were some very violent expressions of opinion on the part of Britishers who had vested interests in this, the first of Germany's Colonies, for there were many private rights concerned, and it was decided that an Anglo-German Commission [Pg 64] should be appointed to inquire into and settle all conflicting claims; but it is not of record that, excepting in regard to the islands, the decisions of the Commission were in favour of the British traders who had for many years been established along the coast of South West Africa.

The result of Luderitz's enterprise, supported by Prussian diplomacy, was, therefore, that the German flag waved over the whole extent of South West Africa from the Orange River to the border of Portuguese Angola, and Angra Pequena assumed the responsibility of the name "Luderitzbucht."

In the meantime Herr Luderitz had established his trading stations at St Lucia Bay on the coast of Zululand, and proceeded to repeat the stratagem he had followed in Angra Pequena by founding trade stations at points inland while he opened negotiations with Dinizulu.

The annexation of South West Africa had, however, caused the British Government to throw off some of their lethargy, and a British warship was dispatched to St Lucia Bay, over which, by virtue of a treaty made with the Zulu King Panda some forty years previously, the British flag was hoisted on the 18th December, 1884.

Danger of the Cape being cut off from the north was, however, still extant in Bechuanaland, where the Boers had annexed the territories known as Stellaland, Goshen, and Rooigrond; but this [Pg 65] was eventually saved to Great Britain by vigorous individual action on the part of Cecil Rhodes, who had himself appointed a Commissioner to visit Bechuanaland, where he strenuously opposed the claims of the Transvaal Republic.

These claims were, however, only withdrawn in the following year after an expedition under Sir Charles Warren had proceeded to the disputed areas and persuaded the Boers that Great Britain was this time in real and eager earnest.

Bechuanaland became a British "Protectorate," and the well-laid scheme for a German transcontinental Empire was frustrated.

The boundaries of the territory brought under German sway in South West Africa were defined by what is known as the Caprivi Treaty of the 1st July, 1890, between Germany and Great Britain, and by an agreement between Germany and Portugal. Under the terms of the latter the northern boundary of German South West Africa, between that Colony and Portuguese Angola, was fixed at the Cunene River; while under the Caprivi Treaty the boundary between the Cape Colony and German South West Africa was declared to be the Orange River.

Great Britain retained Walfisch Bay, which became a "district" of the Cape Colony and was placed under the Colonial administration in 1884, and also kept the territory round Lake 'Ngami in northern Bechuanaland.

The lake district was neglected, however, until Cecil Rhodes, fearing the loss of more territory unless it was beneficially occupied, sent, at his own expense, an expedition of Boer trekkers to settle on the land.

Article III of the Caprivi Treaty was an important one, for thereunder it was provided that Germany should "have free access from her Protectorate (South West Africa) to the Zambezi River by a strip which shall at no point be less than twenty English miles in width."

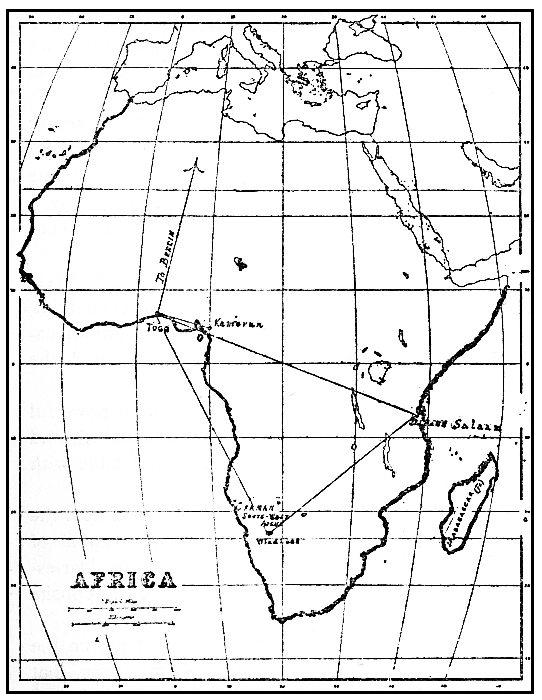

The acquisition by Germany of South West Africa was of great strategical importance, enabling them to establish in time a system of communication by wireless telegraphy which covered the whole continent.

In Togoland on the west coast the most powerful wireless apparatus in the world was installed, and this was in touch both by wireless and cable with Berlin.

The Togoland station was also in touch with the wireless installation at Windhoek, the capital of German South West Africa, and with Dar-es-Salaam, the German port on the east coast opposite Zanzibar.

It is a matter for congratulation, but not on the statesmanship displayed by British ministers, that the fruit of the German essay at the establishment of a "new Empire" in Southern Africa was no more than the annexation of South West Africa, for it is by no means unthinkable that there was a possibility that in addition to the south-west the Germans might have drawn a wide belt right across the continent from west to east, taking in Bechuanaland, the Transvaal, Tongaland, and that portion of Zululand giving the Transvaal an outlet to the east coast at St Lucia Bay.

ILLUSTRATING GERMANY'S WIRELESS SYSTEM EMBRACING AFRICA.

ILLUSTRATING GERMANY'S WIRELESS SYSTEM EMBRACING AFRICA.

The territory hitherto known as German South West Africa covers an area of nearly 323,000 square miles, and has a coastline of 930 miles from the mouth of the Orange River, which separates it from the Cape Colony in the south, to the mouth of the Cunene River, which divides the territory from Portuguese Angola in the north. The southern boundary runs along the Orange River into the interior for some 300 miles.

The German population is stated to be about 15,000, and the natives are estimated at 200,000; but this latter is probably a high calculation, in view of the number who have fled into Bechuanaland and Cape Colony to escape from German tyranny.

One of the first acts of the German Government after their annexation of Damaraland and Great Namaqualand was to declare the claims of British concessionaires invalid.

The "rights" of Herr Luderitz were taken over by a chartered company, incorporated by the Government, which set itself to investigate the resources of the country.

The islands off the coast remained British, and there the huge deposits of guano have been worked for years.

A form of military government was established, who proceeded to impress the natives with the might of Germany; but the Hereros who occupied Damaraland never acknowledged even a German suzerainty, and in 1904 a "rebellion" broke out.

Utterly unaccustomed as they were to warfare of the description they were now called upon to undertake, the Germans found great difficulty in dealing with the "Hottentots," as the natives were termed; and the German effort to destroy the whole tribe involved the employment of 9,000 regular troops and an expenditure of £ 20,000,000.

The Herero War was carried on for nearly three years, and in 1907 was brought to an end by Major Elliott of the Cape Police; for the principal Herero chiefs crossed the borders of the Cape Colony, where they were routed by Major Elliott's force of police and their leaders captured. They were detained for a time by the Cape Government, and finally handed over to the German authorities, by whom they were executed.

Major Elliott was thanked and duly decorated by the Kaiser.

The Germans did not find tribes of natives on whose industry they could batten, and the inhabitants of Great Namaqualand and Damaraland were really unpromising material for such a purpose, not [Pg 71] being pure-bred distinctive tribes, but bastard races with a strong admixture of half-castes.

For decades the territory had been the refuge of criminals and cattle thieves, who had fled from the Cape Colony, after raiding the Bechuana cattle kraals.

A great deal of the coast and part of the southern portion of the Colony is little else than an arid, waterless waste; in fact the rainfall in parts has been known to be half an inch in two years.

Even at Walfisch Bay there is no fresh water to speak of, and for years water for all purposes was brought up the coast by steamers. It is a condition prevailing all along the coast, for even at Port Nolloth in Lesser Namaqualand, south of the Orange River, the inhabitants depend upon water condensed by the sea fogs and dripped from the roofs into tanks, which are by the way kept locked to prevent theft of the precious liquid.

Powerful condensers have, however, for some time been used at various points on the coast to provide fresh water, and this is retailed at a high price.

The Kalahari Desert stretches over the border of the Cape Colony and into Bechuanaland, and contains no surface water; although good results have been obtained by drilling to comparatively shallow depths, and the sandy soil proved highly productive on irrigation.

The desert itself was occupied by nomad bushmen [Pg 72] armed with bows and arrows poisoned by being laid in putrid human flesh, and who kept secret the places where they obtained water. Many of these are pools hidden beneath the earth's surface and from which the water can only be drawn up through a narrow channel by suction through a bamboo reed.

A good substitute for water is found in the wild melons which grow in patches in the driest parts of the Kalahari, and on these police patrols in Bechuanaland have often to rely for water for themselves and animals.

The arid zone is limited, however, and towards the north-east the land gradually rises to an elevated tableland, possessing a dry and one of the most perfect climates in the world.

Approaching Angola again farther north the country becomes almost tropical.

The majority of the veld is of the karoo type, covered with the remarkable karoo bush on the leafless twigs of which sheep thrive and fatten. The salt bush, similar to that valued in Australia for sheep, is found in abundance, but towards the north and coming under the influence of a rainfall the land, while there is no marked geological difference, produces grass instead of the salt bush, and there are belts of rich grass country as fine as any to be found in Southern Africa.

Damaraland is in reality one of the finest cattle countries in Africa, while nearly the whole country [Pg 73] is suitable for sheep and goats. With energetic development there is a big future for it as a producer of hides, wool, and mohair.

Horses do well in many parts of South West Africa; in fact in Namaqualand, along the Orange River, a breed of hardy ponies exists in a semi-wild state. In the drier parts camels are extensively used both by British and German patrols.

The most waterless area near the coast produces a shrub known by the Boers as melk bosch (milk-bush), which carries a plentiful supply of a milky sap which has been manufactured into a fair quality of rubber; but the difficulty of its collection militates against the prospects of its development into a prosperous industry.

The number of head of cattle, the property of the natives but transferred to the Germans by conquest, was, in 1913, estimated at 240,000, wool-bearing sheep 660,000, and other sheep, including Persians, at over 500,000. There were approximately the same number of goats, 20,000 horses, and 3000 ostriches.

In the northerly portion, suitable for agriculture, this was carried on by natives; but their land was confiscated by the Germans, and, as Dr Bönn stated in a reading upon the Colony, "the framework of society is European; very little land is in the hands of natives."

The land was parcelled out into farms and allocated [Pg 74] to companies and Boer settlers, the average size of a farm being about 28,000 acres.

Ostriches are found in many parts in a wild state, and a great number have been domesticated; but the German traders preferred as a rule to rely for their supply of feathers upon the plumes of wild birds killed by the bushmen of the Kalahari.

Of other industries mention might be made of the collection, besides guano, of penguin eggs and seal skins on the islands off the coast, while a few degrees north whalers, operating from Port Alexander, last year accounted for some 3000 whales.

As at the Cape of Good Hope, the whales met with are of the less valuable "hump-backed" variety, but an occasional "right" or sperm whale is captured.

Of ordinary trade there was practically none, as the natives had little or nothing to give in exchange for imported goods; and as for the Boer settler, beyond a little coffee and sugar, he has learned to rely only upon the resources of his farm for his requirement. The natives' only asset of value to the German, his labour, he was not disposed to trade in.

Investigation has revealed the existence of mountains of marble, varied in colour and of a quality equal to Carara; while enormous deposits of gypsum exist.

The whole country is highly mineralised. Silver [Pg 75] first attracted the attention of prospectors but has never been found in payable quantities, although large veins of galena have been traced.

The development of the mineral resources is almost entirely British, and Johannesburg financiers have opened up copper and gold mines.

Enormous deposits of haematite iron and asbestos are known to exist, but so far have not been worked.

Copper, gold, silver, tin, and lead have been worked profitably; but the principal mining industry is diamond washing, and this is mainly in Government hands.

No mine or pipe has been discovered, but the diamonds are found in the loose sand on the foreshore under conditions similar to those prevailing at Diamantina in Brazil.

The diamonds are "dolleyed," and picked out by natives under supervision; but there are a few individual diggers upon whose net production the Government levied a tax.

The output of diamonds in 1913 was valued at £3,000,000, the stones being disposed of under State agency, who occupy the same relative position to the industry as the De Beers Diamond Buying Syndicate to the Kimberley mines.

Diamonds and their concomitants such as olivine, rubies, garnets, etc., have also been discovered on the islands, and in 1906 the discovery of a true pipe was reported on Plum Pudding Island.

A syndicate was formed in England, and an [Pg 76] expedition, fitted out with great secrecy, was sent out in the S.S. Xema; but on arriving at Plum Pudding Island they not only discovered that a tug, dispatched by a Cape Town firm, had visited the island and claimed discoverers' rights, but that by order of the Cape Government no landing was permitted for fear of disturbing the sea-birds, on whom the guano industry depended.