The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Spook Ballads, by William Theodore Parkes

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Spook Ballads

Author: William Theodore Parkes

Release Date: April 20, 2013 [EBook #42566]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SPOOK BALLADS ***

Produced by Irma Spehar, Eleni Christofaki and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note

Minor punctuation inconsistencies have been silently corrected.

Variable, archaic and

unusual spelling as well as apparent printer's errors have been

retained as they appear in the original.

The poems "Bohemians, hail!" and

"Sonnet on shares" do not appear in the table of contents.

SPOOK BALLADS

BY

W. THEODORE PARKES.

Crown 8vo, Cloth gilt, 5s.

Popular Edition 2s.

LONDON:

Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, & Co., Limited.

And all Booksellers.

CHEERS OF THE PRESS!

"Ingoldsby, Thomas Hood, W. S. Gilbert,—these are the names that

occur to one in trying to 'place' Mr. Parkes after reading this volume of

rollicking, verbal and pictorial fun. The Spook Ballads are in no sense imitations

of any of those classics of the comic muse, yet we find in them the same

thorough abandonment to 'the humour of the thing.'"—The Publisher's Circular.

"A substantial volume introducing a Comic Poet, who in the future

may give us a modern Ingoldsby. Mr. Parkes has an intellectual touch to

his drollery and his sense of the possible humours of versification is

pleasantly keen, the Spook Ballads is far above the contemporary average

of the lighter rhymesters. Mr. Parkes wields a sprightly pencil, and he

has illustrated his verses lavishly and with effect."—The Stage.

"Not only are the literary merit of these fantastic ballads of a high

order, but the illustrations by the author are of such a humorous nature

as to give a unique pleasure to the reader."—The Morning Leader.

"Well written, well illustrated, and funny is a combination of good

qualities not often met with even in the Spook world, so Messrs. Simpkin,

Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, and Co., ought to be well pleased with their

publication."—The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.

"Dealing largely with ghosts and legends embracing a dash of diablerie

such as would have been dear to the heart of Ingoldsby. There is a rugged

force in 'The Girl of Castlebar' that will always make it tell in recitation; and

even greater success in this direction has attended 'The Fairy Queen,' a story

unveiling the seamy side, with quaint humour and stern realism. It is specially

worthy of note that Mr. Parkes's skill in versification has received the warmest

acknowledgment from those best qualified to appreciate the bright local coloring

as well as the blending of fancy and fun."—Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper.

"A cheery and spirited production, and full of fun; the style reminds

one of 'Bon Gaultier,' the style and illustrations combined inevitably

recall the famous 'Bab Ballads.' Indeed it is hard to say which is the

most felicitous, the draughtsman or the poet."—The Bookseller.

"In the attractive Spook Ballads, the talented Irish artist has

displayed qualities to a remarkable degree. There are many pieces reciters

will be glad to lay hold of, while the Ballads and Illustrations are full of

the pleasing humour which characterises all Mr. Parkes' work, and which

will serve to cheer and to amuse many readers."—The Sun.

"As the combined production of a clever pencil and a clever pen, this

volume may be said to be unique. These poems are pure fun of the most

entirely frolicsome kind, hung upon the peg of a quaint idea. 'The

German Band' rises to a really tragic pathos. The illustrations are either

quaint, droll, or dainty, or partake of broad caricature."—The Citizen.

"It contains a store of humour that will delight and amuse the reader,

who will be sure to re-read the many capital lays. Just the thing for

reciters. The Artist, his own Illustrator, shines here as conspicuously as

in the kindred branch of Authorship."—British and Colonial Printer and

Stationer.

"Mr. Parkes is clever and polished alike in the expression of humour

and pathos. Indescribably funny is his story of the deluge as told by

'Antediluvian Pat O'Toole,' and a note of grim tragedy is struck in the

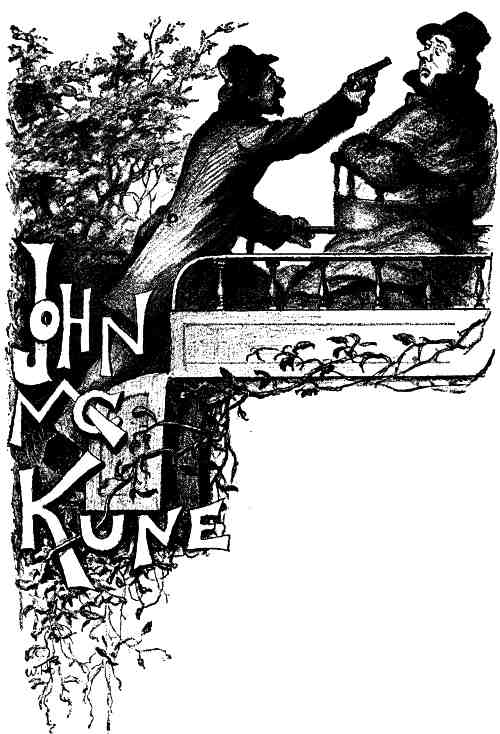

tale of 'John McKune.' Rollicking lays, many of them admirably

adapted for recitation, go to make a delightful book, which has the uncommon

merit of being well illustrated by Mr. Parkes, who is as skilful an

artist as he is an author."—Photographic Journal.

"Spook Ballads possess an amount of boisterous humour and variety

of quaint versification which make them excellent and refreshing reading.

The book owes a good deal of its charm to the author's clever and

laughable illustrations which are plentifully besprinkled in its pages."—The

Weekly Sun.

"There is a good store of pleasant humour in Spook Ballads, by

Theodore Parkes, who also has a happy gift with the pencil, as witness

the illustrations, the fare he provides certainly deserves a really grateful

'grace after meat.'"—The People.

"In his attractive volume, The Spook Ballads, Mr. Theodore Parkes

has shown himself to be not only an author but an artist of considerable

talents."—Weekly Budget.

"The fun is good humoured and light-hearted, and better than most

popular verse as to rhyme and metre. The illustrations are really clever

and range from broad farce to charming little head and tail pieces that are

graceful and suggestive."—Borderland.

"—— Ballads all of which are undeniably clever. A book which will

be gratefully turned to by all who seek occasional relaxation in the best of

good company."—The Surveyor.

"A clever collection of poems illustrated by their author and deserve

great popularity. The author is well known in London literary circles in

which he has given several of the pieces here presented as recitations."—The

Lamp.

"Irrespective of the pleasure to be derived from reading the Ballads,

the book is well worth obtaining for the author's remarkably clever

illustrations."—South London Press.

"A facile flow of versification, keen sense of humour, and a good

mastery of English as she is spoke by Irish, German and other nationalities,

as well as how she should be spoken, characterise this book of ballads.

The sketches are well adapted to the themes."—Manchester Courier.

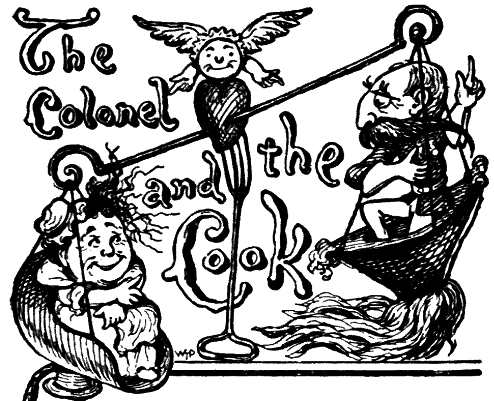

"'The Colonel and the Cook' is not only genuine farce in conception,

but felicitous anti-pathos in the execution."—Manchester Guardian.

"These Ballads are as original and racy and facetious as any I have

come across for a long time; Parkes's pencil is a lively companion for his

pen; the two of them rollick and frolic down page after page in a state of

hilarity that would dissipate and dispose of the worst attack of 'blues.'

The sun does not shine every day, and when the hour is dark and dreary

there will be found enlivement and joviality and wholesome entertainment

within the covers of this volume."—Free Lance in the Weekly Irish Times.

"If any of our readers wish to enjoy a long and pleasant life let

them ask for Spook Ballads! there is abundance of mirth, fun, wit and

merriment in this beautiful volume."—Munster Express.

"About as laugh-inspiring verse as perhaps ever issued from the

Press, the Spook Ballads are one and all conceived in a most

exuberant spirit of drollery. There is a laugh almost in every line,

fun galore bubbles through every page. Where could one find a more

touching combination of humour and pathos than the dedication lines

'Bohemians Hail!' There are lines in it worthy of some of the best touches

of Poe. The book is a book for bon vivants. It is a veritable ode to conviviality,

and its pages teeming with most artistic illustrations. Alive with

ever-recurring flashes of wit and drollery, will afford many a pleasant hour

to all to whom a laugh is welcome."—United Ireland.

"A delightful diverting volume, from cover to cover, of the sixty-one

ballads before us; not one halts, they are all boisterous with bubbling mirth

and frolic. Happy the man who in a moment of ill humour, lights on a copy

of Spook Ballads. Fun of this kind is contagious, and before he has

dipped far into Mr. Parkes' pages he will have forgotten his temper or

his ennui. The book is full too of social satire, with touches of biting

realism."—The Freeman's Journal.

"Most amusingly humorous verses cleverly and quaintly illustrated,

and, like all genuine humour, teaches many a needed and important lesson

in morals and the conduct of life, and hits sharp blows at hypocrisy and

current shams and humbugs. Surely the author must have had Jabez

Balfour and the Liberator swindle in his mind when he composed the scathing

ballad entitled 'The Devil in Richmond Park.'"—The Christian Age.

"This is a very charming and winning volume. Everything about

the book is an incentive to make a prompt acquaintance with its literary

merits. Mr. Parkes is a consummate artist in verse, and through all runs

the same vein of drollery, of pungency, of real humour difficult to resist,

and which makes us wish for more, and much more from so entertaining a

pen."—The Carlow Sentinel.

"A collection of humorous verses quaintly and cleverly illustrated by

his own pencil. The author has a broad vein of humour."—Evening News

(London).

"When parties perusing this volume have completed its 250 pages

they will only regret that it is not double its size."—The Irish Times.

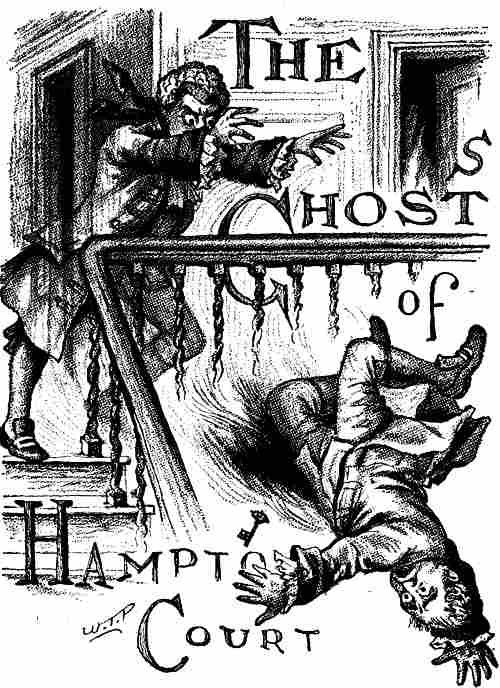

"The naivete of the wit is most irresistible, and the humour most

amusing. 'The Ghost of Hampton Court' and 'The spirit that held him

down' are both decidedly clever, but it is to 'The Girl of Castlebar,' 'The

Fairy Queen' and 'Why did ye die?" we turn for all that is most original

and sparkling. The volume itself is as tastefully finished outside as it is

wittily furnished and illustrated inside."—King's County Chronicle.

"The Spook Ballads will greatly amuse the class of readers who

prefer a good hearty laugh to the emotions produced by 'Paradise lost'

or 'Hamlet.' The book is crammed with fun of the funniest sort, though

it contains many passages which possess a value above mere jollity."—Glasgow

Herald.

"There is no lack of rollicking fun in The Spook Ballads. The pieces

are always amusing in idea, and the free sweep of the verse has a certain

buoyancy which carries a reader pleasantly along."—The Scotsman.

"The humourous drawings are charming, and the figure subjects and

decorative designs show great versatility and skill. Mr. Parkes has a

wonderful way of introducing odd expressions, quaint conceits, and grotesque

imagery. Many a hearty laugh will be got out of the Spook Ballads."—The

Aberdeen Journal.

"The illustrations by the Author copiously strewn throughout the

work are exceedingly clever, and are in themselves enough to commend the

book, and will appeal to readers endowed with a particle of humour.

Altogether the book is the kind to cheer the winter fireside or make the

summer holiday slide joyously into autumn."—Kirkudbrightshire Advertiser.

"The pages abound in illustrations and marginal etchings, and these

display rare artistic skill and a genuine spirit of comicality."—The Derry

Journal.

"John M'Kune is racy of the soil, and rests on something stranger

than fiction."—The Tyrone Constitution.

THE SPOOK BALLADS.

THE

SPOOK BALLADS

BY

WM. THEODORE PARKES

Author of "THE BARNEY BRADEY BROCHURES"

ILLUSTRATED BY THE AUTHOR

LONDON:

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & Co., LIMITED.

1895

BOHEMIANS, HAIL!

The

daylight dreams of many a time,

When song, and rhythmic story,

Were tuned, and voiced for Bigot, and in gay Bohemian ears,

Bring welcome wraiths of joyous nights, thro' whirling clouds of glory;

The incense of the social weed, o'er spirit cup that cheers.

With hail! to Cycle speedmen, and the boaters of Dunleary,

Clontarf, and the Harmonic, where we sang with midnight chimes,

The smokers of Conservatives, and Liberal Unions cheery,

I weave regretful tribute to their jovial social times;

For autumn gales of life have blown those festal hours asunder,

And scattered far by land and sea, the steps of many a one,

And some alas! beneath the sod, for evermore gone under,

Have left a rainbow thro' the mist of grief that they have won.

But slantha! to the hearts, and hands, of those who yet remaining,

Do carry down traditions of that bright Bohemian throng,

And slantha! to the soulful sheen, of life-light never waning

From Old Eblana's heaven of her social art, and song.

And here's to all Bohemians, of whatever rank, or station,

Whatever tint, or black or tan, or creed you are by birth,

Sweet voices of the earth's romance, of every land, or nation,

Hail! brothers, in the carnival of music, song, and mirth:

So fill we tankards, or the glass, for draught with lusty cheering,

Of honor to a crowning toast, with greeting heart and hand,

As everlasting goal, for letters, art, and song, and beering,

Hip, hip, hurrah! vive! hoc! and skoal! to Fleet Street and the Strand!

THE following verses, a remarkable supernatural

interview is narrated. It is now for the first time

launched into publicity, on the authority, and with the approbation of a

quaint old friend of mine, Professor Simon Chuffkrust, a savant who has

daringly groped his way through certain gloomy mysteries of occult science.

THE following verses, a remarkable supernatural

interview is narrated. It is now for the first time

launched into publicity, on the authority, and with the approbation of a

quaint old friend of mine, Professor Simon Chuffkrust, a savant who has

daringly groped his way through certain gloomy mysteries of occult science.

The confidential and impressive manner of Chuffkrust, is jewelled with

eyes of sparkling jet, semitoned behind a screen of moonblue spectacles.

2

His voice is of such convincing suasion, that it is a novel and interesting

experience to hear him relate with circumstantial enthusiasm, the ghostly

interview afforded him by a fortuitous chance within the interesting

grounds of Hampton Court. His is a testimony most reliable, and

calculated to establish as a fact the actual presence of supernatural

shadows in that historic locality.

It also hints at the necessity, and use, of making the ghost a more

familiar study, whereby the belated world would rid itself of much

unnecessary fright, consequent on the invariable habit of spasmodically

avoiding the familiar advances of the common or bedroom spook.

I

N Hampton Court I wandered on a twilight evening grey,

Amidst its mazy precincts I had lost my tourist way,

And while I cogitated, on a seat of carven stone,

I heard beneath an orange tree, an elongated groan!

I crinkled with astonishment, 'twas not a fit of fright,

For loud elastic wailings, I have heard at twelve at night,

The midnight peace disturbing in the lamplit streets below,

But this was uttered in an unfamiliar groan of woe,

And Hampton Court I wot had got some questionable nooks,

In which it harboured spectres, and disreputable spooks,

In which it shrouded headless Queens, and shades of evil Kings

With ill-conditioned titled knaves, in lemans leading strings.

I listened! 'twas a voice that cried as 'twere from out the dust

Of time, that clogged its music, with a husk of mould and rust,

A voice that once as tenor, might have won a slight repute,

But combination now of asthma, whooping cough, and flute.

I sauntered towards the orange tree, and lo! the gloaming thro'

I saw a man in trunk and hose, and silver buckled shoe,

With ruffles and embroidered vest, in wig without a hat,

Inclining to the contour, which is designated fat.

Just then the waxing moonlight bloomed behind, and lifed the stain

3

Of color thro' him, like a Saint upon a window pane,

I could not spare such noted chance; so stepping from the gloom,

I bowed politely and exclaimed

"A Spectre I presume?"

With glad pathetic wondered look, but still in tones of woe,

He answered thus, "Alack! ah me I am exactly so"

And confidential gleam of hope across his features grew,

Which gave me courage thus to start a social interview.

"I pray of thee to speak, alas! why grims it so with thee?

Some evil canker nips thy peace, divulge thy wrongs to me,

That I may give thee hope, for I am one to sympathize

With manhood's lamentation, as with womanhood, her sighs,

But ha! Mayhap it fits your jest, with elongated groan,

To seek to fright me, as I'm here in Hampton Court alone,

To wreck my spirits as of old has been the game of spook,"

The spectre turned upon me with a sad reproachful look.

And cried, "Alack! that living men, so long have held it good,

4

To flee from Ghosts, and hence the Ghost is not yet understood,

Now as for me, I moan it not, for jest of idle sport,

My task, it is as murdered Ghost, to haunt in Hampton Court!

I play the victim to a spook, who chucked me down a stair,

Thro' being caught too near my lady's bedroom unaware."

"Poor shade of ill mischance!" I sobbed, the while a wayward tear,

Tricked out along my nose, and lodged upon my tunic here,

"I pray that thou would'st tell me all, withholding ne'er a jot,

For I might do thee service, in some most unlikely spot,"

"O blessed chance!" the Ghost exclaimed, "Thou art the only one

Of all men else, who spoke me so, they always turn and run!

Thou art the first, that I have seen drop sympathetic tears,

Responsive to my moanings, aye for full one hundred years!

And so I feel that I can speak in unreserving tone,

And give thee cause for this alack! my chronic nightly groan!

When I was in my thirties, I engaged to mind the spoons,

Of Colonel Sir John Bouncer, of the Sixty-fifth Dragoons,

And tho' of lowly stature, I am proud I was by half,

More manly than the footman, by step, and chest, and calf.

With frontispiece well favored, in a frame of powdered wig,

I wot amongst the female sex, I joyed a game of tig,

I played the captivating spark, till Colonel Bouncer caught

Me jesting with my Mistress, and he spake with furious haught,

5

Expressed him his disfavor loud, unto my Lady thus,

"An' thou do not discharge the knave, 'twill cause some future fuss,

The cock-a-dandy bantam, pillory graduate, and scoff

On manhood, give him notice!" but no, she begged me off.

It was not long thereafter, an early postman bore

A warrant for the Colonel, to start for Singapore,

He sailed, and in the August, 'twas just ten months away

He stayed, and he was due in town, upon the first of May,

Twas on that ninth of August at twelve o'clock at night,

'Thro Bouncer Hall I wandered, to see that all was right;

And in my course of searching, to check the silver stock,

I chanced upon the key, with which my Lady wound the clock,

A Louis clock she valued, it was on the mantel shelf

In her boudoir, her habit was to wind it up herself,

I brought it to her bedroom, and scratched a single knock,

And asked her through the keyhole, if she had wound the clock.

My words were scarcely uttered, when from another door,

I heard a foot, that should have been that night in Singapore!

I saw an eye, that should have seen that night a foreign shore,

"Ha! Caitiff knave!!" He shouted,

'Twas all I heard, no more,

6

He collared me by neck, and breech, and swept me off the floor,

And bore me down the corridor,

And hoisting me as light as cork, an act I could not check,

He flung me down the oaken stair, and wanton cracked my neck!

For that he paid the penalty, one day on Tyburn tree,

Alack! it was the sorest deed, the Law could wreak for me

For when it made a Ghost of him, he came, and sought me out,

Where haunting at my Lady's door, I heard the self-same shout,

Of "Caitiff knave!!"

The pity on't! he took me unaware,

Once more by gripping of my breech, and tossed me down the stair!

Night after night he compassed it, nor recked he who was there

But by my crop, and grip of trunks, he bumped me down the stair!

Thus mortified by evil fate, his widow nightly wept,

To hear the periodic row, and scarce a wink she slept;

She daily sought to lay his ghost by penance and by prayer,

And got a brace of saintly monks, to exorcise the scare

7

With holy water sprinked about, a jot he did not care!

But seized me with a fiercer grip, and jocked me down the stair!

And mocked the frightened monks, who flew, with fringe of standing hair.

At last his widow could not reck his evil conduct there,

She moved to otherwhere.

The only tenants that remained in Bouncer Hall, were rats,

Until 'twas taken down, to build some fashionable flats,

And when the workmen moved the stair, I wot he was cut up,

To see its broken banisters, upon a cart put up.

But vengeance of his hate for me, remained a danger yet,

To find a suitable resort, to work it out he set,

And tapped the telephone, until he heard of that resort;

It is an antient oaken stair, that's here in Hampton Court,

'Twas vacant of a Ghost, I faith, a lobby to be let,

And with some Royal Spook, he had a ghostly compact set,

And then he brought me here to work, his midnight murder yet.

An hour ago, accosting me, says he to me, "Prepare!

Be ready! for once more to-night, I'll crock thee down the stair!

To-night, a cousin German of the noble house of Teck

Will occupy the bedroom, and I'll have to crack thy neck!"

In yonder wing, and up the stairs as high as thou canst go,

There is the bedroom, with a door, of casement rather low,

8

And if thou stay a night therein, thy sleep might wake for shock,

Of scratching on the door, and keyhole cry, to wind your clock,

And then the shout of

"Caitiff knave!"

And if thou'rt bold and dare,

To peer out on that lobby then, he crocks me down the stair!

And leaves thee shivering in thy shirt, with fright and besomed hair!

I've heard the County Council, for the City weal is rife,

I'd hold it as a favor, if thou'ds't intimate that life

Is perilled on that lobby, and suggest in thy report,

That lifts would be more suitable, than stairs in Hampton Court.

Then with a comprehensive wail of anguish at his fate,

He gradually vanished thro' the grating of a gate,

And left me sorely puzzled, in a sad reflective state,

Then up a creeping tree, and spout, with stern resolve of hate

Compressed within my breast for Bouncer's evil ghost I clomb,

And slipping thro' the window frame with feline caution dumb,

9

I slid behind a folding screen, and with a craning neck,

I listened for the snoring of the Colonel Van der Teck,

But not a soul had come that night into the room to rest,

There was no cousin German, and the bed was yet unpressed;

A knavish and mendacious trick it was of Bouncer's Ghost,

To crack his butler's neck again, but with some beans and toast,

I picketed behind the door, on eager ear to catch,

The slightest human murmur, thro' the keyhole of the latch,

At last it came! the midnight yet, was booming from a clock,

When lo! a scratching on the door, and half-way thro' the lock,

I heard the question, and with shout, I gave the ghosts a shock,

By springing to the lobby, like a chip of blasting rock!

And bounded twixt the spectres, with the rage of fighting cock,

Then facing Colonel Bouncer's Ghost, "Thou caitiff spook" I cried,

"Was it for this, that Shakespeare wrote, and Colonel Hampden died?

For this! that Cromwell lopped a royal head as traitor knave?

10

For this! that all his cuirassiers were sworn to pray and shave?

Was it for this we lost a world! when George the Third was king?

For this! that laureates have lived of royal deeds to sing?

For this! the printing press was made, torpedoes, dynamite?

The iron ships, and bullet proof cuirass to scape the fight?

Was it for this! we've wove around the world a social net

Of speaking steel, that thou should'st perpetrate thy murder yet?

Out! out on thee! as traitor of thine oath unto the crown!

By gripping of thy butler, by his breech to jock him down,

Was it for this! that justice wrung thy neck on Tyburn tree,

To expiate the direful debt to justice due by thee?

For this! did Lord Macaulay write "The Lays of Antient Rome?"

For this! did Government send out to bring us Jabez home?

Have we been privileged to pay our swollen rates and tax?

And legislative rights imposed upon the noble's backs?

For this! was England parcelled out amongst the Norman few,

That thou should'st haunt in Hampton Court thy noisome work to do?

For this! is London soaring up, to Babel flights of flats

11

As cross between a poorhouse, and a prison?—are top hats

Still worn by busmen, beadles, undertakers, men of prayer!

That thou should'st cause the lieges to irradiate their hair,

With horror at thy felon work? paugh! out upon thee! there!

Thou misbegotten sprite! was it for this! we fought and flew,

On many a bloody battle field, right on to Peterloo?

Thou gall embittered martinet! What boots it if thou crack

Thy butler's neck? Unto that lock, he'll still be harking back,

And grow envigorated, by thy ghastly midnight work,

Like shooting of the chutes, or breezing down the switchback jerk!

"Psha! that unto thee!" and I snapped my finger at him "bosh!

Go, give thy vengeful spirit to contrition, for the wash,

And with the soap of keen remorse, erase the stain of blood,

From out thy soul, and straight atone, with deeds of useful good,

Go, croak behind the Marble Arch, or take a flag and stand

In Grosvenor Square, as captain of a hallelujah band,

Do anything, but mockery of murder, in the dark,

Ay even spout in windy speech, from wagons in the park,

Thou thing of misty cobwebine! thou woman frighter go!

And never more be seen again, to make thyself a show.

For children's fears, or if thou would'st a manly vengeance dare,

Pick up this fourteen stone of mine, and jock me down the stair

Thou idiot spook, thou ill-conditioned cloud concocted sprite

With the immortal bard I cry, Avaunt! and quit my sight!"

12

So fiercely did I thus denounce, his evil midnight trick,

The vigour of the vengeful scowl upon his brow grew sick

With quail of deep abasement, to behold a mortal's blood

On fire, to beard a felon spook, and ghosts were understood,

A transposition of remorse, upon his features came,

Until he shook before me, in an abject wreck of shame,

And cried with tones of keen reproach,

"Adzooks! Alack! Ah me!

Oddsbodikins, well well! heigho! that I should die to see,

My ghost derided, with contempt of scoffing stock from thee!

But of thy clacking caustic tongue, I prithee give no more,

I'll take my passage by a breeze, to-night for Singapore,

Or anywhere the wind may blow, Japan! or Timbuctoo!

To rid me of thy clapper jaw, a flout on thee! Adieu!"

He then evaporated, and with some pride embued,

I turned, for an expression of the butler's gratitude,

But he was gone! and from his place, with india rubber shoe,

A lamp was flashed upon my face, by number 90, Q,

They're never where they're wanted, and that blue, belted elf,

Did hail me up for trespass, and for shouting to myself!

H

E was ye wrothful widowere,

Unto his child spak he,

"Thou art not wise in this my son,

To court with Susan Lee,

A Mayde, ye least that's prattled of,

Ye safer for her fame,

Bethink thee, thou art Jabez Gray,

Respect thy Sire, his name!

14

"Ye reputation of ye Mayde,

Is dewdrop to ye root

Of wedded life, that canks ye blight,

Or ripes ye wholesome fruit,

Then part thee boy, from Susan Lee,

Her ways and lightsome game,

As Jabez Gray, behave thee well,

Respect thy Sire, his name!"

Ah! well a day, for Jabez Gray,

O wallow was his woe,

It stung his heart with pain and rue,

That Mayden Lee should go,

Alack! Ah! me, that such should be,

But compensation came,

For he was true, as Jabez Gray,

Unto his Sire, his name.

15

He gave unto ye Mayde, ye sore,

And sorry last farewell,

Ye pang unto his crinkled heart,

Was gall of woe to tell!

But from his conscience, filial faith,

With healing balsam came

His heart unto, for he was true,

Unto his Sire, his name.

O then 'twas his, 'twas Jabez Gray's

Reward and recompense,

To hear his Sire bespeake ye Mayde,

In fond and future tense,

He pry'd it in ye dark of night,

Beyond ye garden gate,

"I'll wed thee Sue, myself, to save

Thy name from evil prate."

16

He heard ye Sire bespeak ye Mayde,

In tender guise, ye same,

As he did plead, before ye split,

To save ye Sire, his name.

He heard ye Parent, tell to Sue,

Ye lack of manly sense,

Of him, ye son, and with ye kiss,

He spake in future tense.

Ye little month did pass, and then,

Ye Parent wed ye Mayde,

And this, ye counsel to ye son,

In confidence he say'd,

"Ye Spinster Sue is now ye Wife,

Of fair and goodly fame,

Be duteous to her, as ye son

Respect thy Sire, his name!"

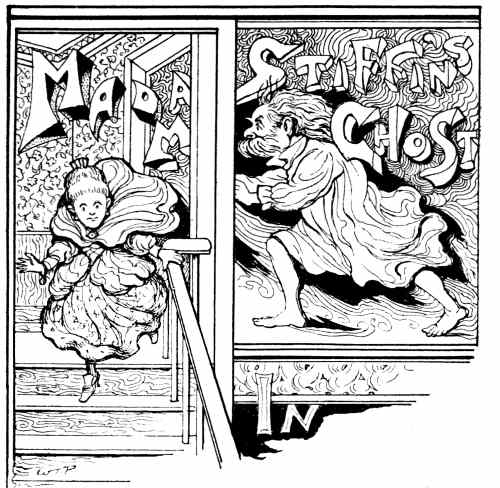

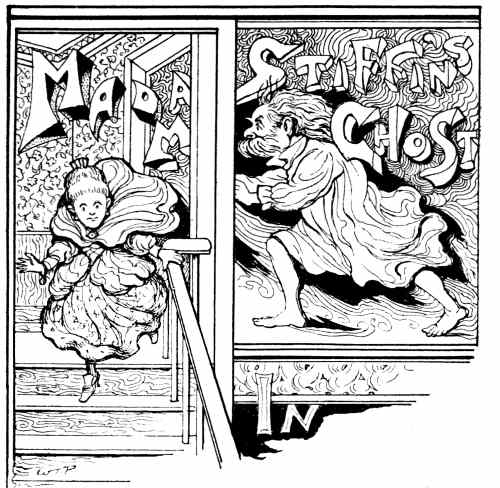

IN

BURTON Crescent, on the semi-circle apex there,

I lodged some little period up a six flight four foot stair,

It came about by freak of chance, 'twas in a cul-de-sac,

I found myself one morning, and compelled to tramp it back,

Whilst blessing gates of London town that bar the traffic yet,

I saw a window label, lettered, "lodgings to be let,"

A gloomy habitation 'twas, to give the nerves the creep!

But possibly a comfortable roosting place to sleep,

Of knockers on its oaken door, it bore a double stock,

I took those knockers, and I struck duet of double knock,

And just as I was rounding off my rallantando din,

The door was gently opened and a lady cried "Come in!"

18I must confess, I fluttered with a flick of some surprise,

To see a lady so petite, and with such piercing eyes,

An artificial bloom was on her cheek, and nose, and neck,

Her gown was of a quaint brocade in antique floral check.

By transmutating hand of time, and his assistant care,

The golden sheen to silver light was paling thro' her hair,

And from the dentistry of art, that crowned her rippled chin,

She greeted me with pearly smile, the moment I stepped in.

I noted on her fingers small, some antique diamond rings,

And in her slippers russet brown, she tripped as 'twere on springs,

A dainty wrap, completed her little quaintly self,

She seemed a living Watteau, that stepped from off a shelf.

She seemed a living Watteau, from out a canvas sprung,

She wasn't—no, she wasn't—well you could not call her young.

She greeted me upsmiling, with business kindled fire,

And volunteered the question,

"What rooms do you require?"

It wasn't my intention, to move upon that day,

My humor was to dawdle, in idle sort of way,

So left it to her option, if twenty rooms or one,

In earth upon the basement, or garret near the sun.

She showed her approbation of my eccentric style,

And greeted me politely, with confidential smile,

"I have a room, the lodger is yet remaining there,

But leaving soon—I'll show it, if you will step the stair.—

She mounted up before me, her little cloak, like wings,

Did supplement her flexor, and her extensor springs,

She paused upon each lobby, to note the pleasing scene,

Of leaves amongst the chimneys, that lent a tint of green.

The sanitary question, she settled with some pains,

Explained, the County Council had just been down the drains,

19

And thus discussing features, and questions to be met,

We landed on the landing of lodging to be let.

Upon the door with knuckle she struck a low rum-tin,

And tardily was answered by husky voice "Come in."

To purpose of her visit, he gave a mild assent,

Which somewhat indicated a debt of backward rent.

We entered the apartment, and gaunt, and wan, and scared!

From tangle of the blankets, blear-eyed, and towsel-haired,

A moment rose the lodger, then underneath the clothes,

He snapped himself like oyster, and only left his nose.

I took a swift synopsis, again we stepped the stair,

She bowed me to her parlour, and all around me there,

Were virtue objects, suited for curioso sale,

Art of the reign of Louis, and good old Chippendale,

Cameo ware of Wedgewood, and Worcester bric-a-brac,

Miniatures of beauties, and oriental lac,

A cabinet and tables, in marquetry of buhl,

And feminine arrangements, of bombazine and tulle.

20

Old mezzotint engravings of Regent, buck and lord,

Between the window curtains, an agèd harpsichord.—

The instrument she fingered, and sang an olden rune,

She sang with taste, but slightly, the strings were out of tune,

She warbled of the Regent, of Sheridan and Burke,

Buck Nash, and of Beau Brummel, and of the fatal work,

Enacted in a duel, then struck a broken string,

And with a sigh she faltered, and then she ceased to sing.

I told her, composition of song, was in my line,

Then, with a look intended as tender and divine,

And mode of days of Brummel, in manner and in style,

She lauded up the bedroom with captivating smile,

Electro-biologic, magnetic in her glance,

She fixed me like a medium, as tenant in advance!

I entered occupation, as soon as I could get,

And everything in order, was for my comfort set,

The room was daily garnished, and swept, my bed was made,

In this was comprehended the lot for which I paid,

My daily mastication, in public grill was frayed,

Monotonous, and easy, with quiet self-content,

I went and came in silence, in silence came and went,

Was no domestic welcome when I came in, not one!

And in the morning ditto, till I was up and gone.

No sound of brush or bucket! no jar of door, or delph!

No foot upon the stairs, except the pair I have myself!

No smutty wench to greet me with cloud of dusty mat!

No snarl of vicious lap dog, or hiss of humping cat!

No slavey whiting up the steps, did ever strike my sight!

Yet everything was fixed for me, when I came home at night!

21

But often on my pillow, when darkness was my ward,

I heard the muffled numbers of distant harpsichord!

I heard a plaintive ballad, to measured cadence set,

Of long ago, that sounded for lordly minuet!

In wierdly notes it fluttered and lingered on the wing,

With wailing for the duel! the sigh! and broken string!

22

But once when I was taking a smoking circumflex,

Around the Burton Crescent, and just at its apex,

I heard a voice behind me, that put me on some toast,

"Look! there's the man, that's living with Madame Stiffin's Ghost!"

I turned, and in the lamplight, distinctly I could see,

A woman's dexter finger, was indicating me!

"He's living as a lodger, above the second floor

Of yonder house, that's haunted, with double-knockered door,

Look! isn't he a cough-drop? it's only such a scare,

Would live in such a lodging, with Madam Stiffin there!"

I never felt so worried at anything before!

Could scarcely find the keyhole of double-knockered door,

And up the stairs I tottered, as in a walking trance,

Next morning, she'd be coming for payment in advance,

Next morning, at the striking of twelve upon the clock,

I started from my slumber, it was her double knock!

I jumped up at the summons, and leaping out of bed,

I answered, and she entered, and unto her I said,

"I'm here thro' false pretences; I understand you're dead!"

A peal of mocking laughter, the little Watteau shook,

And with her arms akimbo, an attitude she struck,

23She made an accusation of drink, and with a glance

Of keen reproach, demanded, her payment in advance!

I had already promised myself, that none should boast,

Of knowing me in future, as tenant of a ghost,

So got my cash, pretending to settle there, and then,

And just as she was lifting my eagle pointed pen,

Said I "Perhaps you'll give me receipt for also this?"

With that I would have tested her presence with a kiss!

I think my arm went thro' her, of that I can't be sure,

But with the table circuit, she took the bedroom door,

I took it quite as quick, and abreviated sight,

I caught of her next landing, and on her hasty flight,

From lobby down to lobby I chased her like a hare,

I tracked her to the kitchen, but lo! she wasn't there!

I flew into the area, back up the stairs I flew,

In drawing-room and parlour, in every bedroom too,

To overtake and seize her, with skidding foot I sped,

And under every sofa, and under every bed,

I searched,—it was a marvel!—exploited every flue,

Unlocked a couple of wardrobes and looked them thro' and thro',

Until in all its horror, the grim conviction grew,

I had in fact been lodging unconscious with a spook!

I rushed to get my waistcoat, pants, traps, and took my hook!

24

H

E travelled by the mail,

On incognito scale,

With cautious care, and reck,

Of varied tricks of art.

For he had made a bag,

Of most extensive swag,

From bank where he was sec.,

And didn't want to part.

But story of his trick,

By telegraphic tick,

Brought him to book, and check,

It gave him quite a start,

He had it by a neck,

'Twas rough to have to part!

HAS been proved by more

than one observant social

Philosopher, that the impressionable star

gazer of the Music Halls is one who often

scatters rose leaves, and harvests thorns;

let us hear what Muffkin Moonhead has to

sing, concerning his own experience.

HAS been proved by more

than one observant social

Philosopher, that the impressionable star

gazer of the Music Halls is one who often

scatters rose leaves, and harvests thorns;

let us hear what Muffkin Moonhead has to

sing, concerning his own experience.

Her photo I declare,

To wear,

With care

Of uttermost esteem,

In pocket of my breast,

That picture lay at rest,

And blest,

With zest,

That fluttered thro' my dream;

26

My dream of love, where she

Was posed, in extacy,

Of gay phantasmagoria,

Of beauty unto me.

Ten other bobs, I pay,

For hothouse plant bouquet,

When she,

On tree,

Of pantomimic treat

In semi-raiment stood,

As geni of the good,

I could,

And would,

Down cast them at her feet.

The feet of love where she

Was posed, in extacy,

Of bright phantasmagoria,

Of beauty unto me!

I took a numbered seat,

In stall select, and neat,

To treat

My sweet!

And when she did appear,

I flung the flow'rs I wis,

She took them, and with this,

O bliss

A kiss!

That thrilled me, while the cheer

Of gods applaudingly,

27

Did greet with storm of glee,

The loved phantasmagoria

Of beauty unto me!

Sweet osculating scene

Of bouquet, and my queen,

And smug

Chaste hug,

Of posies to her nose,

As poising on her toe,

And then subsiding low,

A glow

Flushed so,

On my cheek, like a rose,

The while she bowed the knee,

Then skipped away O.P.,

That lithe phantasmagoria,

Of beauty unto me!

I waited by the door,

Classic door! out they pour,

A score,

Or more,

Escorting her, I say!

And ha! may I be blest,

Upon each jerkin breast,

Confest,

Were drest,

The buds of my bouquet!

28

Said she to me "ta ta!

Go home to your mamma!"

It wrought the rude evanishment

Of love of her from me!

The moral it is this,

Don't dally with such bliss,

A miss,

Is kiss

Unto thee from the play,

A kiss for gods, and stall,

The pit, and tier, on all

To fall

And small

The fig, for your bouquet,

When it has brought the balm,

Of the applauding palm,

She shares it with the supers, and

She gives the chill to thee!

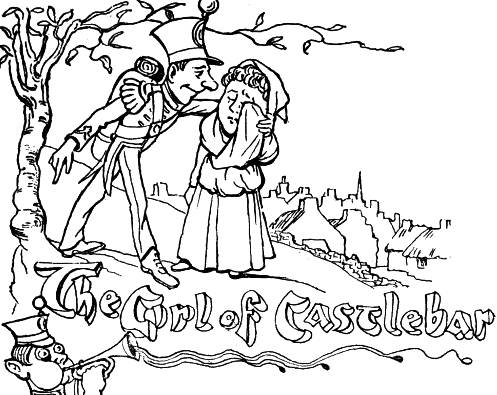

T

HE sun was setting in a gloam of

purple and gold, as I basked in the

grass on the Staball hill one

autumn evening, the stirring tuck

of the tattoo rolled up the slope

from the adjacent barracks; it

affected me like a tonic, my blood

circulated quicker, the spirit of an

amateur ghostly seer took possession

of me! I felt as one inspired.

A scene of early days of Anglo-foreign

strife rose before me like a wraith of second sight. The tramp of

sea-bound red coats, fifes and drums, the woe-mongering cries of parting

wives. I saw two lovers on the Staball hill, heard their vows.

A rhyming fever tingled to my fingers' ends, my only manuscript

medium to hand, the stump of a lead pencil, and blank margin of the

morning paper. Upon that virgin border I jotted the sketch of the

following founded on fact ballad. The reader will perceive in it a

beautiful inverse lesson of the mutual commotion of two loving hearts.

30

T

HE bugle horn was sounding through the streets of Castlebar,

And many a gallant soldier, was bound unto the war,

And one upon the Staball hill, his sweetheart by his side

Swore many a rounded warlike oath, that she should be his bride.

"O Maggie!" cried the Corporal, "There's war across the sea,

And when I'm parted from thee, I would you'd pray for me,

And I will tell you what you'll do, when I am far away,

You'll come up to the Staball, and kneel for me, and pray."

And this to him she promised, and this to him she said,

"I'll still be ever true to thee, be thou alive, or dead!

I'll still be ever true to thee, and O if thou dost fall,

Thy soul at eve will find me here, upon the old Staball."

And then he swore a clinker oath, of what a vengeful doom,

Would him befal, who dared to win her from him, then the bloom

Came to her cheek again, "O Jim I'll never love but you,"

"I'm blowed but I'm the same!" he cried, and then they tore in two!

31

She saw her soldier leaving, she heard the music sweet,

Of "The girl I left behind me" sounding sadly up the street,

She saw the shrieking engine, that bore him far away,

Then went back to the Staball, to weep for him and pray.

And as the summer faded, and gloaming nights came round,

A maid anon was kneeling, upon that trysting ground,

And fearless of the winter, and of its falling snow,

That maiden sweet, and constant, unto her tryst would go.

Till on a certain evening, a stranger in the town,

Came sauntering up the Staball, and found her kneeling down,

He tipped her on the shoulder, and speaking soft, and low,

"O what on earth possesses you, to pray upon the snow."

She told him all her story then, and why so kneeling there,

She told him of her sorrowed heart, the object of her prayer,

She told him of her soldier lad, so far across the sea,

"I'd like to be a soldier lad, with you to love!" said he.

Said he "You're very lonely: If you have need to pray,

I'll come agrah! and help you, with 'Amens' if I may,

It's very hard acushla! to pray alone each night,"

And the colleen shyly answered, "She thought perhaps he might."

The tryst became more social for while the colleen prayed,

The stranger tooted "Amens" unto the kneeling maid,

Until at last he muttered "This pantomime must stop,

I'll buy the ring to-morrow, I've got a watch to pop!"

32

At length the war was over, she heard the beaten drum,

And up again thro' Castlebar, the scarlet men did come,

And her heart grew cold within her, to think how wroth he'd be

To learn she had been faithless, while he was o'er the sea.

Then, pleading to her husband "O hide yerself!" she said,

"Aye even up the chimbledy, or undhernate the bed!

For if he ketches howld of you, I don't know what he'll do,

It's maybe let his gun go off, an' maybe kill the two!

I'll try an' coax the grannies, to brake it to him first,

For if he's towld it sudden by me, 'twill be the worst,

They'll have to put it softly, I cannot be his bride,

So while I'm gone to tell them, do you run off an' hide."

"O break it to him, Grannies, the shocking news," she said

"That I have wed another, and him I cannot wed!

O put it to him gently, for great will be his pain,

That we'll never more be meeting on the Staball hill again."

33

They broke it to him softly, 'twas in a public bar,

A foaming pint before him, and on his brow a scar,

They broke it to him gently, and spoke it to him plain,

He needn't think to meet her, on the Staball hill again.

He swigged the pint before him, then heaved a bitter sigh,

"What? blow me, your a chaffin'!" "O divil a word o' lie!"

Then first he took his shako, and tossed it to the roof,

Then to each nervous grannie, "Here take the bloomin' loof."

"Come, wots yer shout for liquor? It's dooced well!" cried he,

"I'm buckled to a blackimoor, I met beyond the sea,

"You've taken a load from off of me! my mind is now at par,

She wouldn't have left a ribbon on the Girl of Castlebar!"

34

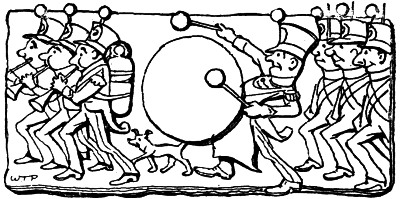

V

E are ze vhandering Shermans,

Ve cooms vrom o'er ze sea,

Ve plays ze lovely music,

Of all ze great countree,

Ve all of us have romance,

Of life, so bigs to say,

I'll sing a verse for each man,

Ze vile ze band vill play.

Vings zerring zanzeraza,

Ve cooms from o'er ze sea,

Ve plays ze lovely music,

Of all ze great countree.

Zare's Herr Von Zingerpofel,

No prouder man vos he,

Zan ven he loved ze Fraulien

Afar in Shermanie.

But ven he found ze noders

Golds ring upon her hand,

He played on ze thriangles,

Und left ze Sherman land!

35

Zare's Blunder Bogle Fogen,

Vot bangs on ze big dhrum,

Thought all ze poor, und rich man,

Should own ze even sum;

Ze government vos differed,

But on ze prison valks,

He doubled up ze gaoler,

Und zen, he valked ze chalks!

Zare's Dreker Mandertoofel,

Ze opheclide he plays,

He'll never more see nodings,

Of all his happiest days;

He only blows ze music,

Because it brings ze cheer,

Of great big pipes of shmokin',

Und shugs of Lager Beer!

Zare's him vot puffs ze oboe,

In oder days vos he,

Of Heidelberg, a student

Ze pride of Shermanie,

But he did love der Lager,

Zoo mooch of Docter-Vien,

He killed ze man in duel!

Und he vos no more seen.

Zare's Mungen Val Tarara,

A Sherman born in Cork,

Und he vos von too many,

Because he vould not vork,

36He left his home von mornings,

Mit all his back hair curled,

He jangs upon ze cymbals,

To bring him round ze vorld.

Now you vill be imagine,

Zat I must oondherstand,

Zat I vill tell ze story

Of leader of ze band,

But if I must, I'll speaks it,

All in ze simple rune,

So I vill stop ze music,

Ze tale is out of tune!

'Twas I vos vonce a Uhlan, who rode mit all ze band,

Zat von Alsace, und Lorraine, from Vrance vor Vaterland,

Ven in ze pits at Gravelotte, I lay von night to die,

I voke! for I vos faintings to hear ze voman sigh!

Und shust vere I vas vounded, I saw ze voman's zere,

Vos bound mine arm from bleeding, mit her own golden hair!

She nursed me through ze danger, und ven zere's peace again,

I svore zat I vould ved her, ze Fraulein of Lorraine.

I kissed my love von mornings, her vite face on my heart,

Mit sobs her eyes vos veeping, ze time vos come to part.

Ze Var vas not yet ended, I heard ze thrompet blow,

Zat I must rise, und answer, und leave ze sveetheart so!

37

Mine blood run cold zat mornings, und I felt somedings here,

Vos in my throat come choking, und on my cheek ze tear,

Vor O I vould not lose her, ze glory on me now,

Zat I vos hope to bless me, mit Cosette vor mine Frau.

I marched avay to Paris, vere all around vos dire,

Mit shmoke, und blood, und thunder, und fret, und woe und fire!

Und ven ze siege vos over, mit thrumpet und mit dhrum,

Vonce more again thro' Lorraine, ze Sherman bands did come.

I vent to find ze sveetheart, but grass vos on ze slain,

Ze cruel Var had murdered ze Fraulein of Lorraine!—

Shust vere mine heart is beating, I keep ze treasure zare,

Mit mine own blood upon it, von braid of golden hair,

Und all dried up und vithered, und gone to dust again,

Von flower zat vonce vos jewelled ze grave zats in Lorraine.

Ah vot is deed of glory, ven blood is on ze vings

Of love, zat makes ze heaven on earth, und vot are kings?

Auch! I vill have no patience. Strike up ze Band again,

Or I grow mad mit dhreamings, vot happened in Lorraine!

Vings zerring zanzaraza, ve cooms from o'er ze sea,

Ve plays ze lovely music, of all ze great countree.

Ve all of us have romance of life so bigs to say,

Vings zerring zanzaraza, ze vile ze band vill play.

38

LAID out pounds, and pounds,

In entertainment rounds,

And worked a score of credit pretty thick,

For I heard she had a plumb,

So invited her to come,

To the altar at shortest notice quick,

When I asked her for my plumb,

She was all but deaf and dumb,

I found that I was married thro' a trick,

To have lifted off the shelf,

A maiden without pelf,

Was unbusiness-like, I felt it was a stick,

Of the candle, all I had was but the wick,

A moody retrospection, makes me sick!

A WARD IN THE CHANCERIE

He

WAS a cabman grey I feck,

All weird and wry to see;

His face was ribbed like the turtle's neck,

His nose like the strawberrie.

If you think he was old, to you I say,

Your thought obscures the truth—

Despite the years that had passed away,

He was still in his second youth.

"Ha! ha!" quoth he, "how fair she looks,"

One morn, as he did see,

A maiden sweet with her school-books,

A ward in the Chancerie.

"How fair she looks!" quoth he, and put

A load in his old black clay,

And he didn't care if he hadn't a fare,

The whole of the live-long day.

40

That night he looketh into the glass,

With his nose like a strawberrie,

"I know they'll say I'm a bloomin' goose

But fate is fate you see."

And he looketh into the glass once more,

Where yet was another drain.

Quoth he, "I've wedded three before,"

"The fourth I'll wed again."

Next day he was out in the open street,

And standing upon the stand,

He heard the trip of her coming feet,

'Twas sweet as a German band.

And forth he went and accosted her,

He could not brook delay,

"Hey up, look here, little gurl," said he,

"I saw you yesterday."

"I saw you yesterday. My 'eart

Went out across your feet,

And from your beauty came a dart

That fixed me all complete;

And all last night I dreamed a dream,

To my bedside you came—

You'll marvel at these words of him

Who does not know your name.

41

"I saw you yesterday. You smile."

His eyes, like burning beads,

Took root in her inmost soul the while,

As deep as the ditch-grown weeds.

"You smile. Ha, ha! to smile and laugh

Is better than aye to frown

It's fitter to whiffle away the chaff

That covers a golden crown.

"It's better to whittle away the cheat

Of mankind if you can."

And he cracked his whip. "It's a fair deceit

And I am a curious man—

Yes I am a curious man, my badge

Is seventeen seventy-seven,

But wot is a badge? It's a very small thing

To the matches wot's made in Heaven!"

"How sweet he speaks!" the maiden thought

"He's a lord in a rough disguise,

As a cabman old he's coming to woo

And give me a grand surprise;

42He seeks to hide himself in a mask,

With a nose like a strawberrie,

But I've read too many of three vol. novs.,

He couldn't disguise from me.

"The Lord of Burleigh while incog.

Did wed an humble bride,

And legend lore recounteth more

Of love like his beside.

I've heard the ballad of Huntingtower,

And some I forget by name,

And when he's got rid of his strawberrie nose

He'll maybe be one of the same!"

And she fondly looked on him, I ween,

Sweet as the hawthorn spray,

When all in bloom of white and green,

It decks the month of May.

"Oh, dearest Cabman," spoke she then,

43

"No brighter fate were mine

Than this: to be thine own laydee,

My life with thee to twine.

"But I am poor and lowly born,

And never a match for thee—

A girl a man like you would scorn,

A ward in the Chancerie,

With only a hundred thousand pounds,

It may be less or more;

But do not wreck a confiding heart,

It often was done before."

"Wo! ho!" quoth he, and in his sleeve

He grinned, "It's a big mistake.

The Chancerie is only a blind,

But, yet, I am wide awake.

44If a hundred thousand pounds wor her's,

She wouldn't be makin' free;

I'd have to court her a little bit more,

Before she'd be courtin' me.

"I haven't the smallest doubt of this—

The truth you tell," he began;

"But I think that you misunderstand me miss,

I am not a marryin' man.

I only thought if you wanted a cab

That I wouldn't be high in my fare,"

And he shuffled the nose-bag round the jaw

Of his patient, hungry mare.

She walked away, nor bade good day,

While he thought of the Probate Court.

"She's a girl, I twig, could give me a dig

Of a barrister's wig for sport.

I have only escaped the courts of law,"

Quoth he, "by a single hair!"

As he finished the knot of his canvas bag

On the nose of his hungry mare.

ANY an intelligent reader will

perceive that the following is a

pathetic plaint founded on fact.

A moral, conveyed in a polyglot sample of

weak passages from many a knowing man's

career.

In one noted instance, the writer while reciting

the ballad, closely escaped the chance of assassination,

at the hand of a member of the audience,

that he fancied it was a versification of his own

particular experience, made public, and brought

so circumstantially home to him, that he felt

the eyes of all were concentrated upon him as the

hero of the ballad. Happily he did not carry a

revolver, or it would most likely have exploded suddenly in the direction

of the platform. But mutual explanations and further enquiry elicited

the information that more than one man of that audience occupied the

same lamplit boat of retrospect misfortune.

Corney Keegan relates his adventure with the picturesque force, derived

from practical experience, and many an aching heart will go out to him

in sympathy. His story teaches a comprehensive, solemn, and beautiful

lesson.

46

M

E mother often spoke to me,

"Corney me boy," siz she,

"There's luck in store for you agra!

You've been so kind to me!

Down be the rath in Reilly's Park

They say that Larry Shawn

That's gone away across the say,

Once cotch a Leprechawn.

He grabbed him be the scruff so hard,

The little crather swore,

That if bowld Larry'd let him go,

He should be poor no more!

"Just look behind ye Larry dear,"

Screeched out the chokin' elf,

"There's hapes of goold in buckets there,

It's all for Larry's self!

If Larry lets the little man

Go free again, he'll be

No longer poor but rich an' great!"

So Larry let him free.

Some say he carried home the goold

An' hid it in the aves,

But some say when the elf was gone

'Twas turned to withered laves.

"If Larry cotch a Leprechawn,"

Me mother then 'ed cry,

"Why you may ketch a fairy queen,

Ma bouchal by an' by!"

Near Balligarry now she sleeps,

47

Where great O'Brien bled,

And often since I took a thought,

Of what me mother said.

At last I came to Dublin town,

To thry an' sell some pigs,

And maybe then I didn't cut

A quare owld shine of rigs.

I sowld me pigs for forty pound,

For they wor clane an' fat,

An' thin we hadn't American mate,

So they wor chape at that!

"Well now," sez I, "me pocket's full,

I'll not go home just yit,

I'll take a twist up thro' the town

An' thrate meself a bit,"

I mosey'd round to Sackville Street,

When starin' round me best,

I seen a darlin' colleen there,

Most beautifully dhressed.

A posy in her leghorn hat,

An' round her neck, a ruff

Of black cock's feathers, jacket too,

Of raal expensive stuff,

A silver ferruled umberell'

In hand with yalla kid,

An' thro' a great big hairy muff

Her other hand was hid,

48

O like a sweet come-all-ye, in

A waltzin' swing, she swep'

The toepath, with the music of

Her silken skirt, an' step,

To see her turn the corner, thro'

The lamplight comin' down,

You'd think she owned the freehowld of

That part of Dublin town!

You'd think she owned the sky above,

It's moon with all the stars,

The thraffic in the streets below,

Their thrams, an' carts, an' cars!

You'd think that she was landlady,

Of all that she could see,

An' faith regardin' of meself,

She made her own of me!

49

"O Corney is it you?" siz she,

An' up to me she came,

I took a start, to hear her there,

Pronouncin' out me name;

"O Corney, there ye are!" siz she

Wid raal familiar smile,

An' thin begar she took me arm,

Most coaxingly the while;

I fluttered like a butterfly,

That's born the first of May,

Wid pride, as if I had the right

Hand side, the Judgment Day!

I felt as airy as a lark that

Skies it from the ground,

To think she'd walk wid me, poor chap,

Wid only forty pound!

She took me arm, an' thrapsed wid me,

All down be Sackville Sthreet,

An' colleens beautifully dhressed,

In two's and three's, we meet,

An' men that grinned, a greenish grin,

Of envy from their eye,

To see me wid that lady grand,

Like paycock marchin' by.

Till comin' to a lamp, I turned,

An' gazed into her eyes,

Me heart that minute took me throat

Wid lump of glad surprise,

50

Siz I, "Me jewel, thim two eyes,

Are sparklin' awful keen,

"I'm sure," siz I, "I've come across,

Me mother's Fairy Queen!"

"O Corney yis," siz she, "I am,

A Fairy Queen;" siz she,

"An' I can make yer fortune now,

If you'll just come with me."

Wid that, I ups and says "of coorse!"

As bowld as I could spake,

"An' sure I will me darlin', if

Its only for your sake."

Well, whin we passed the statutes white,

Up to O'Connell Brudge,

The Fairy Queen smiled up at me,

An' gev a knowin' nudge,

"Corney!" siz she, "I want a dhrink!"

51

"Do ye me dear?" siz I,

An' on the minute faith I felt,

Meself was shockin' dhry.

Well then she brought me coorsin off,

Down be the Liffy's walls,

An' up a narra gloomy sthreet,

Up to a Palace Halls!

An' there they wor, all splindid lit,

"Come in me love," siz she.

I thought me heart'ed brake, to hear

Her spake so kind to me!

Well in we wint, an' down we sat,

Behind a marvel schreen,

An' there we dhrank, of drink galore,

Me an' the Fairy Queen.

She spoke by alphabetic signs,

Siz she, "We'll have J.J.

An' whin we swalley'd that, siz she,

"L.L. is raal O.K."

We tossed them off like milk, siz she,

"At these we need'nt stick,

D. W. D.'s a quench you'll find,

A. I, an' up to Dick!"

Well thin she left the alphabet,

An' flying to the sky,

"The three star brand's the best" siz she,

"To sparkle up your eye,"

Thin "here!" says she "just taste Owld Tom,"

But augh! agin me grain

It wint! siz she "It's mum's the word,

52

We'll cure it, wid champagne!"

I never drank such sortin's, of

The drink, in all me life,

Signs on it, in the mornin', me

Digestion, was at strife!

At last, we qualified our drooth,

An' up she got, siz she,

"We'll just retire to private life,

So Corney, come wid me."

But just before I stood to go,

I siz quite aisy "Miss,

You might bestow poor Corney K.

One little simple kiss."

"Ah! Corney tibbey, sure," said she,

"Two if ye like, ye thrush!"

O have ye saw the blackberries,

Upon the brambly bush?

The Johnny Magory still is bright,

Whin all the flowers are dead,

Her hair, was like the blackberries!

Her dhress, Magory red!

O have you ever saunthered out

Upon a winther's night,

Whin the crispy frost, is on the ground,

An' all the stars, are bright?

Then have you bent your awe sthrick gaze,

There, up aginst the skies?

The stars are very bright, you think,

Well thim was just her eyes

53

Were you ever down at the strawberry beds,

An' seen them dhrowned in chrame?

Well that was her complexion, and

Her teeth, wor shockin' white!

An' the music of her laughin' chaff,

Was like a beggar's dhrame,

Whin he hears the silver jingle, and

His rags are out of sight!

I thought the dhrop of dhrink was free,

But throth I had to pay!

I thought it quare, but then I thought,

It was the fairy's way;

"Howld on" siz I, "she's thryin' me,

Have I an open heart,

Before she makes me fortune," so,

Begar! I took a start

Of reckless generosity,

An' flung me money round,

54

'Twas scatthered on the table! In

Her lap, an' on the ground!

I seen it glitter in the air,

Before me wondherin' eyes,

Like little yalla breasted imps,

All dhroppin from the skies!

O then I knew that it was threw,

She was a Fairy Queen,

The goold, came dhroppin'! whoppin'! hoppin'

The like was never seen!

I gave a whipping screech of joy!

Whin, wid a sudden whack,

Some hidden wizard, riz his wand,

An' sthruck me from the back,

Down came the clout upon the brain,

An' froze me senses quite,

An' over all me joy at once,

There shot the darkest night!

I knew no more, till I awoke,

An' found meself alone,

I thrust me hand, to grasp me purse,

Me forty pounds wor gone!

O then, with awful cursin', if

I didn't raise the scenes,

"Bad luck!" siz I, "to Leprechauns,

Bad scran, to Fairy Queens!

Bad luck to them, that spreads abroad,

Such shockin' lyin' tales,

Bad scran has me, that tears me hair,

55

An' forty pounds bewails!"

With that, I seen a man, come up,

A dark arch, marchin' thro',

As if he hadn't any work,

Particular to do.

He measured me, wid selfish eye,

As cat regards a rat,

An' whin he spoke, begor I found,

'Twas just his price at that!

Siz he "What's all this squealin' for?

What makes ye bawl?" siz he,

Siz he, "I'm a dissective, so,

You'll have to come wid me!"

Siz he, "Yer shouts wor almost loud

Enough, to crack the delph!

An' in the mornin' I must bring

Ye up, before himself!"

"Arrah! What for?" siz I, an' thin,

I towld him all me woe,

An' how I woke, an' found meself

Asleep, an' lyin' low.

I towld him of the whipsther, that

Had whipped me forty pound,

An' left me lyin' fast asleep,

In gutther, on the ground.

Then leerin' like, he turned, and siz,

"You're a nice boy! complate!

To go wid Fairy Queens, like that,

An' lose yer purse, so nate.

Corney!" siz he, "go home!" siz he,

"She might have sarved ye worse,

56

I'll thry me best, to ketch the Fay,

An' get you back yer purse.

But look! don't shout like that again,

It was a shockin' shout,

It sthruck me, 'twas a house a-fire!

You riz up such a rout.

I thought you'd wake me wife! she sleeps,

Down in a churchyard near!"

Wid that, the dark dissective turned,

An' bursted in a tear!

I dhribbled out a few meself,

Me brow, wid shame I bint,

An' like a lamb, from slaughter, slow,

Wid tottherin' steps I wint,

But never, never from that day,

Was any tidins' seen,

Of me owld purse, me forty pound!

Or of the Fairy Queen!

Then, whin I thought of Norah's wrath,

An' what a power she'd say,

Me fine black hair, riz on me skull,

An' grew all grizzle gray!

O never more, to Dublin town,

I'll come, to sell me pigs!

I walk a melancholy man,

Like one, that's got the jigs,

An' in the town of Limerick, if

You ever chance, to meet

A haggard man, wid batthered hat,

Come sthridin down the sthreet,

57

An' if he stops, by fits and starts,

An' stares at nothin' keen!

Say "there goes Corney, look he's mad!

He cotch a Fairy Queen."

And if you chance in Sackville Sthreet,

Or any other way,

To meet, all beautifully dhrest,

A lovely colleen gay;

An' if she chances on the name,

That you wor christened by,

An' laughs, as if she knew ye,

With a cute acquaintance eye,

An' if she takes your arm, an' siz,

That she's a Fairy Queen,

Start back in horror, shout aloud,

O woman am I green!

Am I before a doctor's shop,

Where coloured bottles be?

Is there a green light, on my face,

That you should spake to me?

Go home, O Fairy Queen, go home!

At once, an' holus bolus!

Remimber, Corney Keegan's purse,

An' think of the Dublin Polis

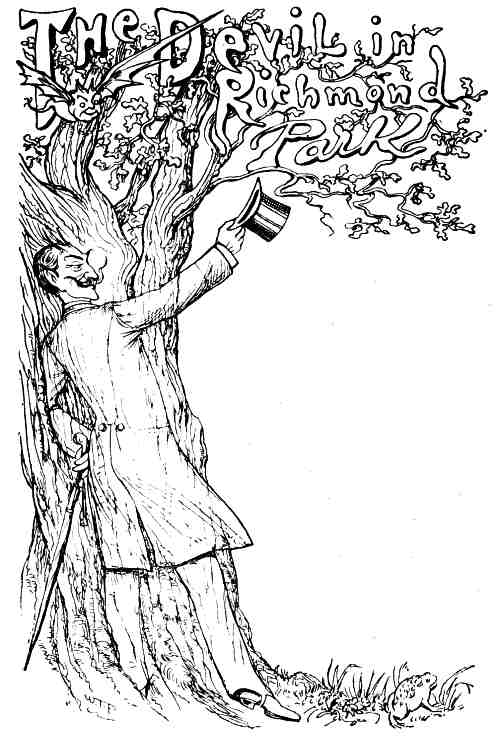

THE DEVIL IN RICHMOND PARK

I

WAS walking about, in a casual way,

Thro' the ferns, in Richmond Park,

'Twas just at the fringe of the twilight hour,

On the skirt, of the time called dark,

And the wind was rough, and I couldn't succeed,

To kindle my three-penny smoke,

When a gentleman stepped from behind a tree,

And coughed, and hemmed, and spoke:

59

"You'll pardon me, Sir, you're in want of a light,"

Said he, with a bow to me,

And straight producing a braided star,

He struck it against his knee,

And with an expression of much concern,

To see that my weed was right,

He manipulated the light himself,

With a courtesy most polite.

I am one, who is quickly impressed, and won,

By measure of courteous act,

So deeming it right, to appreciate,

In response of appropriate tact,

I spake to him thus, "It's rare that a man

In a gentleman's dress like thine,

Doth care to assist, the frivolous wants,

Of a miniature vice like mine,

So reckon it not, as a rudeness wrought,

Of an ignorant wish to know,

But I'd certainly like to learn the name,

Of the gent, who has touched me so!

Then he glittered a grin, from his cat-like eye,

Thro' a coal black lash on me,

And he bowed, with his lifted silk top hat,

"I'm the Devil himself!" quoth he.

Good gracious! yes, I was certainly struck,

So suddenly thus to be

With the Devil himself! but soon, or late,

He was bound to appear to me.

60

So screwing my nerves, to concert pitch,

To play up my soul, for wealth,

With a supplemental proviso made,

For excellent mortal health,

I offered to scribble my autograph,

In blood, old-storied style,

To deed, for a compensating line,

From his notable strong room pile.

But he looked on me, with a pitying glance,

I counted somewhat queer,

And answered me thus,—in a friendly way,

With a slight sarcastic leer.

T'S a long time, Sir, I assure you, since

I endeavoured, to so combine,

My games of spoof, for the human soul,

In the bartering oofftish line.

I suffered by many a measly cheat,

When mortals made those sales,

You'll read of their shuffling knavish tricks,

Thro' the mediæval tales,

If you think, that by selling your soul to me,

Is the way to get rich, it ain't,

You'll have to become, a Devil yourself,

In the garb, of a modern Saint.

61

"It's the fashionable way, to play the game,

Of hypocritical spoof,

You have only to tailor your saintly robe,

To cover your tell tale hoof,

You have only to hypnotise mankind,

And teach them, to gaze on high,

And while you have mesmerised them thus,

With eyes, to the upward sky,

"You can plot, exploit, and sneak, and trick,

And cram your wallet, with wares,

And earthly stocks, as you boom the run,

On the New Jerusalem shares,

You can rob the widow, and orphan child;

But reputably go to church,

And if, by the clogging of circumstance,

Your pinched, in the doomdock lurch,

The greater the pile of swag, you've made,

The fewer the blanks, you'll draw,

From the lottery wheel, of the English bench,

In the name, of the English law.

It's merely a mode, of paying yourself,

In advance, a liberal wage,

For the government work, you'll have to do,

In the broad-arrow-branded stage.

Say thirty thousands of pounds, you filch,

Five years, is the time you'll do,

Six thousand a year, in advance, you see,

To enjoy, when you've pulled it thro'.

Or, seizing your pile, by a dextrous coup,

Before they have time, to look down,

62

From the castles, in the air,

You have built for them there,

You can take a foreign ticket from town.

"And tho' you are lagged, at the ends of the earth,

You'll still find a breach, or a flaw,

Whereby you can slip, thro' the quips, that confuse,

Extradition—international law.

"Now that is how I teach, the quickest way to cure,

Your impecuniosity complaint,

You must collar the swag, as a Devil yourself,

In the garb, of a modern saint.

There's another way to pinch, whereby you may keep,

Your character, apparently sound,

Go pray, and exhort, teach the vanity of wealth,

And pay, half-a-crown in the pound!

"Now bear it in mind, if you're wanting to make,

Let this, be your measureless plaint,

The misery of wealth, get a halo, and preach,

In the garb, of a modern Saint."

Again he lifted his silk top hat,

And bowing an adieu to me,

He vanished away, with a lordly crawl,

In the trunk, of the nearest tree,

And thus, were my mediæval hopes

Of wealth, by a caustic blow,

Dispersed, and a lesson of evil taught,

By the Devil, who touched me so.

I PICTURED out my passion,

In florid fretwork fashion,

Expostulating!

Waiting!

Stating,

Mating we must be,

And subtle thought, relating,

To scheme, of emigrating,

With bride, to land of Bashan,

Was exercising me;

When, peering like a picket,

Or a cricket,

From a thicket,

Thro' the wicket,

Came another, on the scene,

And we were three!

'Twas the spinster, in a hurried

Fit of minorhood, I married,

She succoured me

From bigamy,

Said she,

"Come home to tea!"

I went, and drank it boiling,—

A mug of strong Bohea!—

I drank it, without sugar,

A tannic dose, for me!

64

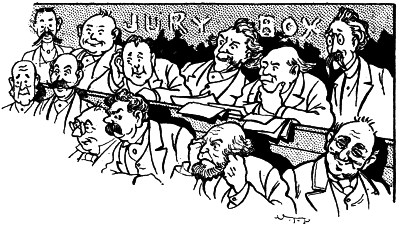

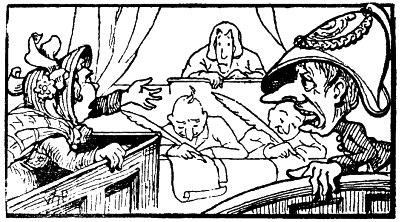

'T

WAS an incident Matrimonial, the Probate Court the place,

And 'twas for the co-respondent, a most remarkable case,

For good was the leading counsel, and moral the words spake he,

And fashionable ladies listened, to Writ MacFee, Q.C.

He rose to his feet and setting his most magniloquent frown,

He fingered his brief for a moment, a moment, and laid it down,

Then out of his golden snuffbox, he powdered his pampered nose,

And then with a pull back rustle of silk, to its wonted pose,

He heliographed to the jury, a glitter of eyeful glee,

And as he surveyed the respondent, most rep-re-hen-siv-lee,

He mounted his golden pinc-nez, and on this wise spake he.

65"Me Lud, and O gents of the Jury, it's a most remarkable case!

And I don't hesitate for a moment, my cause in your hands to place,

For O," said the counsellor, purring, with subtle seductive leer,

"I never beheld such a jury, in the length of my long career!

I assure you it makes it easy for an advocate like to me,

To open the most remarkable case ver. Tommins, L.R.C.P."

Then marking his condemnation, with voice like a double bass D.

"The co-respond' is a doctor, John Tommins, L.R.C.P.,

A leech of the muddiest water, a pill, that has given the sick,

An emetic of truth, a plaister of pitch, with a warrant to stick,

It's O when consumptive virtue, is treated by such, you see

The ruin, like that enacted by Tommins, L.R.C.P.

He was called to attend the Lady May Monica Pendigrew,

From a fit of the blues he roused her, and prettily pulled her through,

But managed her like a pilot, who getting a treacherous grip,

Sails out into deeper water, to scuttle and sink the ship!

O gents, by æsthetical fraud, he played on the lady's mind,

With Shakespeare collar and fur, a sunflower, and such kind,

He called her too utterly too, and posed in a limpish style,

And droned in a minorly key, of love, like a fretwork file.

Me Lud, and O gentlemen, gents, the co-respond' may smile,

Your sympathy thus to win, by means of trover of guile,

But no! you will give him a check, whereby you will take your place,

As the most remarkable twelve, of the most remarkable case!"

66

'Twas thus, with vigour, and vim, and verve, and casuist glee,

The raftered roof re-echoed, the shouts of Writ MacFee,

While envious briefless Bees, admired his logic, and gist,

Accentuate note, and pause, well marked by his thumping fist,

He stood on the councillor's seat, with one of his feet—the left,

And the stuffy compression of air, with whirling silk he cleft,

And this, was his winding up, "O Father, Brother, and Son,

Oh this is a case, concerning each individual one,

And confident of your verdict, now into your hands I place,