The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Palace of Pleasure, Volume 1, by William Painter This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Palace of Pleasure, Volume 1 Author: William Painter Release Date: January 1, 2007 [EBook #20241] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PALACE OF PLEASURE *** Produced by Louise Hope, Carlo Traverso and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF/Gallica) at http://gallica.bnf.fr and The Internet Archive at http://www.archive.org)

The first seven pages of the printed book have been moved to the end of this section of the e-text.

In the introduction, the spelling “Giovanne” (Boccaccio) is used more often than “Giovanni”. Unless otherwise noted, brackets [ ] and question marks (?) are in the original.

Note that “Tome I” refers to the two-volume editions of Painter and Haslewood, while “Volume I” refers to Jacobs’s three-volume edition (the present text). Tome I goes up to Novel LXVI (i.66); Volume I ends at Novel XLVI (i.46).

Indented or italicized items were added by the transcriber. Italicized terms do not appear in the printed text. The “Tome I” link leads to a separate file containing novels I - XLVI.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | ix |

| INTRODUCTION | xi |

| PRELIMINARY MATTER (FROM HASLEWOOD) | xxxvii |

| Bibliographical Notices | xlv |

| liii | |

| lxiii | |

| The Second Tome | lxxxi |

| INDEX OF NOVELS | xcii |

| Footnotes | end |

TOME I. |

separate file |

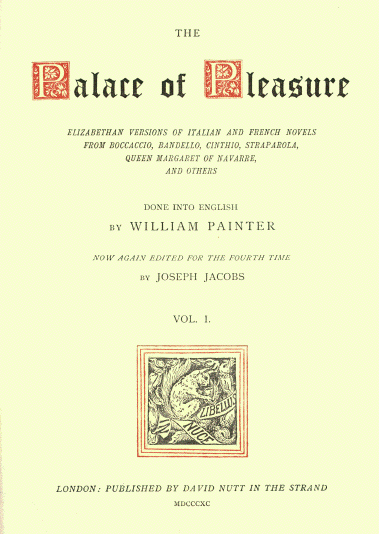

The present edition of Painter’s “Palace of Pleasure,” the storehouse of Elizabethan plot, follows page for page and line for line the privately printed and very limited edition made by Joseph Haslewood in 1813. One of the 172 copies then printed by him has been used as “copy” for the printer, but this has been revised in proof from the British Museum examples of the second edition of 1575. The collation has for the most part only served to confirm Haslewood’s reputation for careful editing. Though the present edition can claim to come nearer the original in many thousands of passages, it is chiefly in the mint and cummin of capitals and italics that we have been able to improve on Haslewood: in all the weightier matters of editing he shows only the minimum of fallibility. We have however divided his two tomes, for greater convenience, into three volumes of as nearly as possible equal size. This arrangement has enabled us to give the title pages of both editions of the two tomes, those of the first edition in facsimile, those of the second (at the beginning of vols. ii. and iii.) with as near an approach to the original as modern founts of type will permit.

I have also reprinted Haslewood’s “Preliminary Matter,” which give the Dryasdust details about the biography of Painter and the bibliography of his book in a manner not too Dryasdust. With regard to the literary apparatus of the book, I have x perhaps been able to add something to Haslewood’s work. From the Record Office and British Museum I have given a number of documents about Painter, and have recovered the only extant letter of our author. I have also gone more thoroughly into the literary history of each of the stories in the “Palace of Pleasure” than Haslewood thought it necessary to do. I have found Oesterley’s edition of Kirchhof and Landau’s Quellen des Dekameron useful for this purpose. I have to thank Dr. F. J. Furnivall for lending me his copies of Bandello and Belleforest.

I trust it will be found that the present issue is worthy of a work which, with North’s “Plutarch” and Holinshed’s “Chronicle,” was the main source of Shakespeare’s Plays. It had also, as early as 1580, been ransacked to furnish plots for the stage, and was used by almost all the great masters of the Elizabethan drama. Quite apart from this source of interest, the “Palace of Pleasure” contains the first English translations from the Decameron, the Heptameron, from Bandello, Cinthio and Straparola, and thus forms a link between Italy and England. Indeed as the Italian novelle form part of that continuous stream of literary tradition and influence which is common to all the great nations of Europe, Painter’s book may be termed a link connecting England with European literature. Such a book as this is surely one of the landmarks of English literature.

xiA young man, trained in the strictest sect of the Pharisees, is awakened one morning, and told that he has come into the absolute possession of a very great fortune in lands and wealth. The time may come when he may know himself and his powers more thoroughly, but never again, as on that morn, will he feel such an exultant sense of mastery over the world and his fortunes. That image1 seems to me to explain better than any other that remarkable outburst of literary activity which makes the Elizabethan Period unique in English literature, and only paralleled in the world’s literature by the century after Marathon, when Athens first knew herself. With Elizabeth England came of age, and at the same time entered into possession of immense spiritual treasures, which were as novel as they were extensive. A New World promised adventures to the adventurous, untold wealth to the enterprising. The Orient had become newly known. The Old World of literature had been born anew. The Bible spoke for the first time in a tongue understanded of the people. Man faced his God and his fate without any intervention of Pope or priest. Even the very earth beneath his feet began to move. Instead of a universe with dimensions known and circumscribed with Dantesque minuteness, the mystic glow of the unknown had settled down on the whole face of Nature, who offered her secrets to the first comer. No wonder the Elizabethans were filled with an exulting sense of man’s capabilities, when they had all these realms of thought and action suddenly and at once thrown open before them. There is a confidence in the future and all it had xii to bring which can never recur, for while man may come into even greater treasures of wealth or thought than the Elizabethans dreamed of, they can never be as new to us as they were to them. The sublime confidence of Bacon in the future of science, of which he knew so little, and that little wrongly, is thus eminently and characteristically Elizabethan.2

The department of Elizabethan literature in which this exuberant energy found its most characteristic expression was the Drama, and that for a very simple though strange reason. To be truly great a literature must be addressed to the nation as a whole. The subtle influence of audience on author is shown equally though conversely in works written only for sections of a nation. Now in the sixteenth century any literature that should address the English nation as a whole—not necessarily all Englishmen, but all classes of Englishmen—could not be in any literary form intended to be merely read. For the majority of Englishmen could not read. Hence they could only be approached by literature when read or recited to them in church or theatre. The latter form was already familiar to them in the Miracle Plays and Mysteries, which had been adopted by the Church as the best means of acquainting the populace with Sacred History. The audiences of the Miracle Plays were prepared for the representation of human action on the stage. Meanwhile, from translation and imitation, young scholars at the universities had become familiar with some of the masterpieces of Ancient Drama, and with the laws of dramatic form. But where were they to seek for matter to fill out these forms? Where were they, in short, to get their plots?

Plot, we know, is pattern as applied to human action. A story, whether told or acted, must tend in some definite direction if it is to be a story at all. And the directions in which stories can go are singularly few. Somebody in the Athenæum—probably Mr. Theodore Watts, he has the habit of saying such things—has remarked that during the past century only two novelties in plot, xiii Undine and Monte Christo, have been produced in European literature. Be that as it may, nothing strikes the student of comparative literature so much as the paucity of plots throughout literature and the universal tendency to borrow plots rather than attempt the almost impossible task of inventing them. That tendency is shown at its highest in the Elizabethan Drama. Even Shakespeare is as much a plagiarist or as wise an artist, call it which you will, as the meanest of his fellows.

Not alone is it difficult to invent a plot; it is even difficult to see one in real life. When the denouement comes, indeed—when the wife flees or commits suicide—when bosom friends part, or brothers speak no more—we may know that there has been the conflict of character or the clash of temperaments which go to make the tragedies of life. But to recognise these opposing forces before they come to the critical point requires somewhat rarer qualities. There must be a quasi-scientific interest in life quâ life, a dispassionate detachment from the events observed, and at the same time an artistic capacity for selecting the cardinal points in the action. Such an attitude can only be attained in an older civilisation, when individuality has emerged out of nationalism. In Europe of the sixteenth century the only country which had reached this stage was Italy.

The literary and spiritual development of Italy has always been conditioned by its historic position as the heir of Rome. Great nations, as M. Renan has remarked, work themselves out in effecting their greatness. The reason is that their great products overshadow all later production, and prevent all competition by their very greatness. When once a nation has worked up its mythic element into an epos, it contains in itself no further materials out of which an epos can be elaborated. So Italian literature has always been overshadowed by Latin literature. Italian writers, especially in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, were always conscious of their past, and dared not compete with the great names of Virgil, Ovid, Horace, and the rest. At the same time, with this consciousness of the past, they had evolved a special interest in the problems and arts of the present. The split-up of the peninsula into so many small states, many of xiv them republics, had developed individual life just as the city-states of Hellas had done in ancient times. The main interest shifted from the state and the nation to the life and development of the individual.3 And with this interest arose in the literary sphere the dramatic narrative of human action—the Novella.

The genealogy of the Novella is short but curious. The first known collection of tales in modern European literature dealing with the tragic and comic aspects of daily life was that made by Petrus Alphonsi, a baptized Spanish Jew, who knew some Arabic.4 His book, the Disciplina Clericalis, was originally intended as seasoning for sermons, and very strong seasoning they must have been found. The stories were translated into French, and thus gave rise to the Fabliau, which allowed full expression to the esprit Gaulois. From France the Fabliau passed to Italy, and came ultimately into the hands of Boccaccio, under whose influence it became transformed into the Novella.5

It is an elementary mistake to associate Boccaccio’s name with the tales of gayer tone traceable to the Fabliaux. He initiated the custom of mixing tragic with the comic tales. Nearly all the novelle of the Fourth Day, for example, deal with tragic topics. And the example he set in this way was followed by the whole school of Novellieri. As Painter’s book is so largely due to them, a few words on the Novellieri used by him seem desirable, reserving for the present the question of his treatment of their text.

Of Giovanne Boccaccio himself it is difficult for any one with a love of letters to speak in few or measured words. He may have been a Philistine, as Mr. Symonds calls him, but he was surely a Philistine of genius. He has the supreme virtue of style. In fact, it may be roughly said that in Europe for nearly two centuries there is no such thing as a prose style but Boccaccio’s. xv Even when dealing with his grosser topics—and these he derived from others—he half disarms disgust by the lightness of his touch. And he could tell a tale, one of the most difficult of literary tasks. When he deals with graver actions, if he does not always rise to the occasion, he never fails to give the due impression of seriousness and dignity. It is not for nothing that the Decamerone has been the storehouse of poetic inspiration for nearly five centuries. In this country alone, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dryden, Keats, Tennyson, have each in turn gone to Boccaccio for material.

In his own country he is the fountainhead of a wide stream of literary influences that has ever broadened as it flowed. Between the fifteenth and the eighteenth centuries the Italian presses poured forth some four thousand novelle, all avowedly tracing from Boccaccio.6 Many of these, it is true, were imitations of the gayer strains of Boccaccio’s genius. But a considerable proportion of them have a sterner tone, and deal with the weightier matters of life, and in this they had none but the master for their model. The gloom of the Black Death settles down over the greater part of all this literature. Every memorable outburst of the fiercer passions of men that occurred in Italy, the land of passion, for all these years, found record in a novella of Boccaccio’s followers. The Novelle answered in some respects to our newspaper reports of trials and the earlier Last Speech and Confession. But the example of Boccaccio raised these gruesome topics into the region of art. Often these tragedies are reported of the true actors; still more often under the disguise of fictitious names, that enabled the narrator to have more of the artist’s freedom in dealing with such topics.

The other Novellieri from whom Painter drew inspiration may be dismissed very shortly. Of Ser Giovanne Fiorentino, who wrote the fifty novels of his Pecorone about 1378, little is known nor need be known; his merits of style or matter do not raise him above mediocrity. Straparola’s Piacevole Notti were composed in Venice in the earlier half of the sixteenth century, and are chiefly interesting xvi for the fact that some dozen or so of his seventy-four stories are folk-tales taken from the mouth of the people, and were the first thus collected: Straparola was the earliest Grimm. His contemporary Giraldi, known as Cinthio (or Cinzio), intended his Ecatomithi to include one hundred novelle, but they never reached beyond seventy; he has the grace to cause the ladies to retire when the men relate their smoking-room anecdotes of feminine impudiche. Owing to Dryden’s statement “Shakespeare’s plots are in the one hundred novels of Cinthio” (Preface to Astrologer), his name has been generally fixed upon as the representative Italian novelist from whom the Elizabethans drew their plots. As a matter of fact only “Othello” (Ecat. iii. 7), and “Measure for Measure” (ib. viii. 5), can be clearly traced to him, though “Twelfth Night” has some similarity with Cinthio’s “Gravina” (v. 8): both come from a common source, Bandello.

Bandello is indeed the next greatest name among the Novellieri after that of Boccaccio, and has perhaps had even a greater influence on dramatic literature than his master. Matteo Bandello was born at the end of the fifteenth century at Castelnuovo di Scrivia near Tortona. He lived mainly in Milan, at the Dominican monastery of Sta. Maria delle Grazie, where Leonardo painted his “Last Supper.” As he belonged to the French party, he had to leave Milan when it was taken by the Spaniards in 1525, and after some wanderings settled in France near Agen. About 1550 he was appointed Bishop of Agen by Henri II., and he died some time after 1561. To do him justice, he only received the revenues of his see, the episcopal functions of which were performed by the Bishop of Grasse. His novelle are nothing less than episcopal in tone and he had the grace to omit his dignity from his title-pages.

Indeed Bandello’s novels7 reflect as in a mirror all the worst sides of Italian Renaissance life. The complete collapse of all the older sanctions of right conduct, the execrable example given by the petty courts, the heads of which were reckless because their position was so insecure, the great growth of wealth and xvii luxury, all combined to make Italy one huge hot-bed of unblushing vice. The very interest in individuality, the spectator-attitude towards life, made men ready to treat life as one large experiment, and for such purposes vice is as important as right living even though it ultimately turns out to be as humdrum as virtue. The Italian nobles treated life in this experimental way and the novels of Bandello and others give us the results of their experiments. The Novellieri were thus the “realists” of their day and of them all Bandello was the most realistic. He claims to give only incidents that really happened and makes this his excuse for telling many incidents that should never have happened. It is but fair to add that his most vicious tales are his dullest.

That cannot be said of Queen Margaret of Navarre, who carries on the tradition of the Novellieri, and is represented in Painter by some of her best stories. She intended to give a Decameron of one hundred stories—the number comes from the Cento novelle antichi, before Boccaccio—but only got so far as the second novel of the eighth day. As she had finished seven days her collection is known as the Heptameron. How much of it she wrote herself is a point on which the doctors dispute. She had in her court men like Clement Marot, and Bonaventure des Périers, who probably wrote some of the stories. Bonaventure des Périers in particular, had done much in the same line under his own name, notably the collection known as Cymbalum Mundi. Marguerite’s other works hardly prepare us for the narrative skill, the easy grace of style and the knowledge of certain aspects of life shown in the Heptameron. On the other hand the framework, which is more elaborate than in Boccaccio or any of his school, is certainly from one hand, and the book does not seem one that could have been connected with the Queen’s name unless she had really had much to do with it. Much of its piquancy comes from the thought of the association of one whose life was on the whole quite blameless with anecdotes of a most blameworthy style. Unlike the lady in the French novel who liked to play at innocent games with persons who were not innocent, Margaret seems to have liked to talk and write of things xviii not innocent while remaining unspotted herself. Her case is not a solitary one.

The whole literature of the Novella has the attraction of graceful naughtiness in which vice, as Burke put it, loses half its evil by losing all its grossness. At all times, and for all time probably, similar tales, more broad than long, will form favourite talk or reading of adolescent males. They are, so to speak, pimples of the soul which synchronise with similar excrescences of the skin. Some men have the art of never growing old in this respect, but I cannot say I envy them their eternal youth. However, we are not much concerned with tales of this class on the present occasion. Very few of the novelle selected by Painter for translation depend for their attraction on mere naughtiness. In matters of sex the sublime and the ridiculous are more than usually close neighbours. It is the tragic side of such relations that attracted Painter, and it was this fact that gave his book its importance for the history of English literature, both in its connection with Italian letters and in its own internal development.

The relations of Italy and England in matters literary are due to the revivers of the New Learning. Italy was, and still is, the repository of all the chief MSS. of the Greek and Latin classics. Thither, therefore, went all the young Englishmen, whom the influence of Erasmus had bitten with a desire for the New Learning which was the Old Learning born anew. But in Italy itself, the New Learning had even by the early years of the sixteenth century produced its natural result of giving birth to a national literature (Ariosto, Trissino). Thus in their search for the New Learning, Englishmen of culture who went to Italy came back with a tincture of what may be called the Newest Learning, the revival of Italian Literature.

Sir Thomas Wyatt and the Earl of Surrey “The Dioscuri of the Dawn” as they have been called, are the representatives of this new movement in English thought and literature, which came close on the heels of the New Learning represented by Colet, More, Henry VIII. himself and Roger Ascham. The adherents of the New Learning did not look with too favourable eyes on xix the favourers of the Newest Learning. They took their ground not only on literary lines, but with distinct reference to manners and morals. The corruption of the Papal Court which had been the chief motive cause of the Reformation—men judge creeds by the character they produce, not by the logical consistency of their tenets—had spread throughout Italian society. The Englishmen who came to know Italian society could not avoid being contaminated by the contact. The Italians themselves observed the effect and summed it up in their proverb, Inglese italianato è un diabolo incarnato. What struck the Italians must have been still more noticeable to Englishmen. We have a remarkable proof of this in an interpolation made by Roger Ascham at the end of the first part of his Schoolmaster, which from internal evidence must have been written about 1568, the year after the appearance of Painter’s Second Tome.8 The whole passage is so significant of the relations of the chief living exponent of the New Learning to the appearance of what I have called the Newest Learning that it deserves to be quoted in full in any introduction to the book in which the Newest Learning found its most characteristic embodiment. I think too I shall be able to prove that there is a distinct and significant reference to Painter in the passage (pp. 77-85 of Arber’s edition, slightly abridged).

But I am affraide, that ouer many of our trauelers into Italie, do not exchewe the way to Circes Court: but go, and ryde, and runne, and flie thether, they make great hast to cum to her: they make great sute to serue her: yea, I could point out some with my finger, that neuer had gone out of England, but onelie to serue Circes, in Italie. Vanitie and vice, and any licence to ill liuyng in England was counted stale and rude vnto them. And so, beyng Mules and Horses before they went, returned verie Swyne and Asses home agayne; yet euerie where verie Foxes with as suttle and busie heades; and where they may, verie Woolues, with cruell malicious hartes. A trewe Picture of a knight of Circes Court. A maruelous monster, which, for filthines of liuyng, for dulnes to learning him selfe, for wilinesse in dealing with others, for malice in hurting without cause, should carie at once in one bodie, the belie of a Swyne, the head of an Asse, the brayne of a Foxe, the wombe of a xx wolfe. If you thinke, we iudge amisse, and write to sore against you, heare, The Italians iudgement of Englishmen brought vp in Italie. what the Italian sayth of the English Man, what the master reporteth of the scholer: who vttereth playnlie, what is taught by him, and what learned by you, saying Englese Italianato, e vn diabolo incarnato, that is to say, you remaine men in shape and facion, but becum deuils in life and condition. This is not, the opinion of one, for some priuate spite, but the iudgement of all, in a common Prouerbe, which riseth, of that learnyng, and those maners, which you gather in Italie: The Italian diffameth them selfe, to shame the Englishe man. a good Scholehouse of wholesome doctrine, and worthy Masters of commendable Scholers, where the Master had rather diffame hym selfe for hys teachyng, than not shame his Scholer for his learnyng. A good nature of the maister, and faire conditions of the scholers. And now chose you, you Italian Englishe men, whether you will be angrie with vs, for calling you monsters, or with the Italianes, for callyng you deuils, or else with your owne selues, that take so much paines, and go so farre, to make your selues both. If some yet do not well vnderstand, An English man Italianated. what is an English man Italianated, I will plainlie tell him. He, that by liuing, and traueling in Italie, bringeth home into England out of Italie, the Religion, the learning, the policie, the experience, the maners of Italie.... These be the inchantements of Circes, brought out of Italie, to marre mens maners in England; much, by example of ill life, but more by preceptes of fonde bookes, Italian bokes translated into English. of late translated out of Italian into English, sold in euery shop in London, commended by honest titles the soner to corrupt honest maners: dedicated ouer boldlie to vertuous and honourable personages, the easielier to begile simple and innocent wittes. It is pitie, that those, which haue authoritie and charge, to allow and dissalow bookes to be printed, be no more circumspect herein, than they are. Ten Sermons at Paules Crosse do not so moch good for mouyng men to trewe doctrine, as one of those bookes do harme, with inticing men to ill liuing. Yea, I say farder, those bookes, tend not so moch to corrupt honest liuing, as they do, to subuert trewe Religion. Mo Papistes be made, by your mery bookes of Italie, than by your earnest bookes of Louain....

Therfore, when the busie and open Papistes abroad, could not, by their contentious bookes, turne men in England fast enough, from troth and right iudgement in doctrine, than the sutle and secrete Papistes at home, procured bawdie bookes to be translated out of the Italian tonge, whereby ouer many yong willes and wittes xxi allured to wantonnes, do now boldly contemne all seuere bookes that founde to honestie and godlines. In our forefathers tyme, whan Papistrie, as a standyng poole, couered and ouerflowed all England, fewe bookes were read in our tong, sauyng certaine bookes of Cheualrie, as they sayd, for pastime and pleasure, which, as some say, were made in Monasteries, by idle Monkes, or wanton Chanons: as one for example, Morte Arthur. Morte Arthure: the whole pleasure of which booke standeth in two speciall poyntes, in open mans slaughter, and bold bawdrye: In which booke those be counted the noblest Knightes, that do kill most men without any quarrell, and commit fowlest aduoulteres by subtlest shiftes: as Sir Launcelote, with the wife of king Arthure his master: Syr Tristram with the wife of king Marke his vncle: Syr Lamerocke with the wife of king Lote, that was his owne aunte. This is good stuffe, for wise men to laughe att or honest men to take pleasure at. Yet I know, when Gods Bible was banished the Court, and Morte Arthure receiued into the Princes chamber. What toyes, the dayly readyng of such a booke, may worke in the will of a yong ientleman, or a yong mayde, that liueth welthelie and idlelie, wise men can iudge, and honest men do pitie. And yet ten Morte Arthures do not the tenth part so much harme, as one of these bookes, made in Italie, and translated in England. They open, not fond and common ways to vice, but such subtle, cunnyng, new, and diuerse shiftes, to cary yong willes to vanitie, and yong wittes to mischief, to teach old bawdes new schole poyntes, as the simple head of an Englishman is not hable to inuent, nor neuer was hard of in England before, yea when Papistrie ouerflowed all. Suffer these bookes to be read, and they shall soone displace all bookes of godly learnyng. For they, carying the will to vanitie and marryng good maners, shall easily corrupt the mynde with ill opinions, and false iudgement in doctrine: first, to thinke nothyng of God hym selfe, one speciall pointe that is to be learned in Italie, and Italian bookes. And that which is most to be lamented, and therfore more nedefull to be looked to, there be moe of these vngratious bookes set out in Printe within these fewe monethes, than haue bene sene in England many score yeare before. And bicause our English men made Italians can not hurt, but certaine persons, and in certaine places, therfore these Italian bookes are made English, to bryng mischief enough openly and boldly, to all states great and meane, yong and old, euery where.

And thus yow see, how will intised to wantonnes, doth easelie allure the mynde to false opinions: and how corrupt maners in liuinge, breede xxii false iudgement in doctrine: how sinne and fleshlines, bring forth sectes and heresies: And therefore suffer not vaine bookes to breede vanitie in mens wills, if yow would haue Goddes trothe take roote in mens myndes....

They geuing themselues vp to vanitie, shakinge of the motions of Grace, driuing from them the feare of God, and running headlong into all sinne, first, lustelie contemne God, than scornefullie mocke his worde, and also spitefullie hate and hurte all well willers thereof. Then they haue in more reuerence the triumphes of Petrarche: than the Genesis of Moses: They make more account of Tullies offices, than S. Paules epistles: of a tale in Bocace, than a storie of the Bible. Than they counte as Fables, the holie misteries of Christian Religion. They make Christ and his Gospell, onelie serue Ciuill pollicie: Than neyther Religion cummeth amisse to them....

For where they dare, in cumpanie where they like, they boldlie laughe to scorne both protestant and Papist. They care for no scripture: They make no counte of generall councels: they contemne the consent of the Chirch: They passe for no Doctores: They mocke the Pope: They raile on Luther: They allow neyther side: They like none, but onelie themselues: The marke they shote at, the ende they looke for, the heauen they desire, is onelie, their owne present pleasure, and priuate proffit: whereby, they plainlie declare, of whose schole, of what Religion they be: that is, Epicures in liuing, and ἄθεοι in doctrine: this last worde, is no more vnknowne now to plaine Englishe men, than the Person was vnknown somtyme in England, vntill som Englishe man tooke peines to fetch that deuelish opinin out of Italie....

I was once in Italie my selfe: but I thanke God, my abode there, was but ix. dayes: Venice. And yet I sawe in that litle time, in one Citie, more libertie to sinne, than euer I hard tell of in our noble London. Citie of London in ix. yeare. I sawe, it was there, as free to sinne, not onelie without all punishment, but also without any mans marking, as it is free in the Citie of London, to chose, without all blame, whether a man lust to weare Shoo or Pantocle....

Our Italians bring home with them other faultes from Italie, though not so great as this of Religion, yet a great deale greater, than many good men will beare. Contempt of mariage. For commonlie they cum home, common contemners of mariage and readie persuaders of all other to the same: not because they loue virginitie, nor yet because they hate prettie yong virgines, but, being free in Italie, to go whither so euer lust will cary them, they do not like, that lawe and honestie should be soche a barre to their like libertie at home in England. And xxiii yet they be, the greatest makers of loue, the daylie daliers, with such pleasant wordes, with such smilyng and secret countenances, with such signes, tokens, wagers, purposed to be lost, before they were purposed to be made, with bargaines of wearing colours, floures and herbes, to breede occasion of ofter meeting of him and her, and bolder talking of this and that, etc. And although I haue seene some, innocent of ill, and stayde in all honestie, that haue vsed these thinges without all harme, without all suspicion of harme, yet these knackes were brought first into England by them, that learned them before in Italie in Circes Court: and how Courtlie curtesses so euer they be counted now, yet, if the meaning and maners of some that do vse them, were somewhat amended, it were no great hurt, neither to them selues, nor to others....

An other propertie of this our English Italians is, to be meruelous singular in all their matters: Singular in knowledge, ignorant in nothyng: So singular in wisedome (in their owne opinion) as scarse they counte the best Counsellor the Prince hath, comparable with them: Common discoursers of all matters: busie searchers of most secret affaires: open flatterers of great men: priuie mislikers of good men: Faire speakers, with smiling countenances, and much curtessie openlie to all men. Ready bakbiters, sore nippers, and spitefull reporters priuily of good men. And beyng brought vp in Italie, in some free Citie, as all Cities be there: where a man may freelie discourse against what he will, against whom he lust: against any Prince, agaynst any gouernement, yea against God him selfe, and his whole Religion: where he must be, either Guelphe or Gibiline, either French or Spanish: and alwayes compelled to be of some partie, of some faction, he shall neuer be compelled to be of any Religion: And if he medle not ouer much with Christes true Religion, he shall haue free libertie to embrace all Religions, and becum, if he lust at once, without any let or punishment, Iewish, Turkish, Papish, and Deuilish.

It is the old quarrel of classicists and Romanticists, of the ancien régime and the new school in literature, which runs nearly through every age. It might be Victor Cousin reproving Victor Hugo, or, say, M. Renan protesting, if he could protest, against M. Zola. Nor is the diatribe against the evil communication that had corrupted good manners any novelty in the quarrel. Critics have practically recognised that letters are a reflex of life long before Matthew Arnold formulated the relation. And in the disputing between Classicists and Romanticists it has invariably happened xxiv that the Classicists were the earlier generation, and therefore more given to convention, while the Romanticists were likely to be experimental in life as in literature. Altogether then, we must discount somewhat Ascham’s fierce denunciation, of the Italianate Englishman, and of the Englishing of Italian books.

There can be little doubt, I think, that in the denunciation of the “bawdie stories” introduced from Italy, Ascham was thinking mainly and chiefly of Painter’s “Palace of Pleasure.” The whole passage is later than the death of Sir Thomas Sackville in 1566, and necessarily before the death of Ascham in December 1568. Painter’s First Tome appeared in 1566, and his Second Tome in 1567. Of its immediate and striking success there can be no doubt. A second edition of the first Tome appeared in 1569, the year after Ascham’s death, and a second edition of the whole work in 1575, the first Tome thus going through three editions in nine years. It is therefore practically certain that Ascham had Painter’s book in his mind9 in the above passage, which may be taken as a contemporary criticism of Painter, from the point of view of an adherent of the New-Old Learning, who conveniently forgot that scarcely a single one of the Latin classics is free from somewhat similar blemishes to those he found in Painter and his fellow-translators from the Italian.

But it is time to turn to the book which roused Ascham’s ire so greatly, and to learn something of it and its author.10 William Painter was probably a Kentishman, born somewhere about 1525.11 He seems to have taken his degree at one of the Universities, as we find him head master of Sevenoaks’ school about 1560, and the head master had to be a Bachelor of Arts. In the next year, however, he left the pædagogic toga for some connection with arms, for on 9 Feb. 1561, he was appointed xxv Clerk of the Ordnance, with a stipend of eightpence per diem, and it is in that character that he figures on his title page. He soon after married Dorothy Bonham of Dowling (born about 1537, died 1617), and had a family of at least five children. He acquired two important manors in Gillingham, co. Kent, East Court and Twidall. Haslewood is somewhat at a loss to account for these possessions. From documents I have discovered and printed in an Appendix, it becomes only too clear, I fear, that Painter’s fortune had the same origin as too many private fortunes, in peculation of public funds.

So far as we can judge from the materials at our disposal, it would seem that Painter obtained his money by a very barefaced procedure. He seems to have moved powder and other materials of war from Windsor to the Tower, charged for them on delivery at the latter place as if they had been freshly bought, and pocketed the proceeds. On the other hand, it is fair to Painter to say that we only have the word of his accusers for the statement, though both he and his son own to certain undefined irregularities. It is, at any rate, something in his favour that he remained in office till his death, unless he was kept there on the principle of setting a peculator to catch a peculator. I fancy, too, that the Earl of Warwick was implicated in his misdeeds, and saved him from their consequences.

His works are but few. A translation from the Latin account, by Nicholas Moffan, of the death of the Sultan Solyman,12 was made by him in 1557. In 1560 an address in prose, prefixed to Dr. W. Fulke’s Antiprognosticon, was signed “Your familiar friend, William Paynter,”13 and dated “From Sevenoke xxii. of Octobre;” and the same volume contains Latin verses entitled “Gulielmi Painteri, ludimagistri Seuenochensis Tetrastichon.” It is perhaps worth while remarking that this Antiprognosticon was directed against Anthony Ascham, Roger’s brother, which may perhaps account for some of the bitterness in the above passage from the Scholemaster. These slight productions, however, xxvi sink into insignificance in comparison with his chief work, “The Palace of Pleasure.”

He seems to have started work on this before he left Seven Oaks in 1561. For as early as 1562 he got a licence for a work to be entitled “The Citye of Cyuelite,” as we know from the following entry in the Stationers’ Registers:—

W. Jonnes—Receyued of Wylliam Jonnes for his lycense for pryntinge of a boke intituled The Cytie of Cyuelitie translated into englisshe by William Paynter.

From his own history of the work given in the dedication of the first Tome to his patron, the Earl of Warwick, it is probable that this was originally intended to include only tales from Livy and the Latin historians. He seems later to have determined on adding certain of Boccaccio’s novels, and the opportune appearance of a French translation of Bandello in 1559 caused him to add half a dozen or so from the Bishop of Agen. Thus a book which was originally intended to be another contribution to the New Learning of classical antiquity turned out to be the most important representative in English of the Newest Learning of Italy. With the change of plan came a change of title, and the “City of Civility,” which was to have appeared in 1562, was replaced by the “Palace of Pleasure” in 1566.14

The success of the book seems to have been immediate. We have seen above Ascham’s indignant testimony to this, and the appearance of the Second Tome, half as large again as the other, within about eighteen months of the First, confirms his account. This Second Tome was practically the Bandello volume; more than half of the tales, and those by far the longest, were taken from him, through the medium of his French translators, Boaistuau and Belleforest. Within a couple of years another edition was called for of the First Tome, which appeared in 1569, with the addition of five more stories from the Heptameron, from which eleven were already in the first edition. Thus the First Tome might be called the Heptameron volume, and the second, that of Bandello. Boccaccio is pretty xxvii evenly divided between the two, and the remainder is made up of classic tales and anecdotes and a few novelle of Ser Giovanni and Straparola. Both Tomes were reprinted in what may be called the definitive edition of the work in 1575.

Quite apart from its popularity and its influence on the English stage, on which we shall have more to say shortly, Painter’s book deserves a larger place in the history of English Literature than has as yet been given to it. It introduced to England some of the best novels of Boccaccio, Bandello, and Queen Margaret, three of the best raconteurs of short stories the world has ever had. It is besides the largest work in English prose that appeared between the Morte Darthur and North’s Plutarch.15 Painter’s style bears the impress of French models. Though professing to be from Italian novellieri, it is mainly derived from French translations of them. Indeed, but for the presence of translations from Ser Giovanni and Straparola, it might be doubtful whether Painter translated from the Italian at all. He claims however to do this from Boccaccio, and as he owns the aid of a French “crib” in the case of Bandello, the claim may be admitted. His translations from the French are very accurate, and only err in the way of too much literalness.16 From a former dominie one would have expected a far larger proportion of Latinisms than we actually find. As a rule, his sentences are relatively short, and he is tolerably free from the vice of the long periods that were brought into vogue by “Ciceronianism.” He is naturally free from Euphuism and for a very good reason, since Euphues and his Englande was not published for another dozen years or so. The recent suggestion of Dr. Landmann and others that Euphuism came from the influence of Guevara would seem to be negatived by the fact that the “Letters of Trajan” in the Second Tome of Painter are taken from Guevara and are no more Euphuistic than the rest of the volume.

Painter’s volume is practically the earliest volume of prose translations xxviii from a modern language into English in the true Elizabethan period after the influence of Caxton in literary importation had died away with Bourchier the translator of Froissart and of Huon of Bordeaux. It set the ball rolling in this direction, and found many followers, some of whom may be referred to as having had an influence only second to that of Painter in providing plots for the Elizabethan Drama. There can be little doubt that it was Painter set the fashion, and one of his chief followers recognised this, as we shall see, on his title page.

The year in which Painter’s Second Tome appeared saw George (afterwards Sir George) Fenton’s Certaine Tragicall Discourses writtene oute of Frenche and Latine containing fourteen “histories.” As four of these are identical with tales contained in Painter’s Second Tome it is probable that Fenton worked independently, though it was doubtless the success of the “Palace of Pleasure” that induced Thomas Marshe, Painter’s printer, to undertake a similar volume from Fenton. The Tragicall Discourses ran into a second edition in 1569. T. Fortescue’s Foreste or Collection of Histories ... dooen oute of Frenche appeared in 1571 and reached a second edition in 1576. In the latter year appeared a work of G. Pettie that bore on its title page—A Petite Palace of Pettie his Pleasure—a clear reference to Painter’s book. Notwithstanding Anthony à Wood’s contemptuous judgment of his great-uncle’s book it ran through no less than six editions between 1576 and 1613.17 The year after Pettie’s first edition appeared R. Smyth’s Stravnge and Tragicall histories Translated out of French. In 1576 was also published the first of George Whetstone’s collections of tales, the four parts of The Rocke of Regard, in which he told over again in verse several stories already better told by Painter. In the same year, 1576, appeared G. Turberville’s Tragical Tales, translated out of sundrie Italians—ten tales in verse, chiefly from Boccaccio. Whetstone’s Heptameron of Ciuill Discourses in 1582 was however a more important contribution to the English Novella, xxix and it ran through two further editions by 1593.18 Thus in the quarter of a century 1565-1590 no less than eight collections, most of them running into a second edition, made their appearance in England. Painter’s work contains more than all the rest put together, and its success was the cause of the whole movement. It clearly answered a want and thus created a demand. It remains to consider the want which was thus satisfied by Painter and his school.

The quarter of a century from 1565 to 1590 was the seed-time of the Elizabethan Drama, which blossomed out in the latter year in Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great. The only play which precedes that period, Gordobuc or Ferrex and Porrex, first played in 1561, indicates what direction the English Drama would naturally have taken if nothing had intervened to take it out of its course. Gordobuc is severely classical in its unities; it is of the Senecan species. Now throughout Western Europe this was the type of the modern drama,19 and it dominated the more serious side of the French stage down to the time of Victor Hugo. There can be little doubt that the English Drama would have followed the classical models but for one thing. The flood of Italian novelle introduced into England by Painter and his school, imported a new condition into the problem. It is essential to the Classical Drama that the plot should be already known to the audience, that there should be but one main action, and but one tone, tragic or comic. In Painter’s work and those of his followers, the would-be dramatists of Elizabeth’s time had offered to them a super-abundance of actions quite novel to their audience, and alternating between grave and gay, often within the same story.20 The very fact of their foreignness was a further attraction. At a time when all things were new, and intellectual curiosity had become a passion, the opportunity xxx of studying the varied life of an historic country like Italy lent an additional charm to the translated novelle. In an interesting essay on the “Italy of the Elizabethan Dramatists,”21 Vernon Lee remarks that it was the very strangeness and horror of Italian life as compared with the dull decorum of English households that had its attraction for the Elizabethans. She writes as if the dramatists were themselves acquainted with the life they depicted. As a matter of fact, not a single one of the Elizabethan dramatists, as far as I know, was personally acquainted with Italy.22 This knowledge of Italian life and crime was almost entirely derived from the works of Painter and his school. If there had been anything corresponding to them dealing with the tragic aspects of English life, the Elizabethan dramatists would have been equally ready to tell of English vice and criminality. They used Holinshed and Fabyan readily enough for their “Histories.” They would have used an English Bandello with equal readiness had he existed. But an English Bandello could not have existed at a time when the English folk had not arrived at self-consciousness, and had besides no regular school of tale-tellers like the Italians. It was then only from the Italians that the Elizabethan dramatists could have got a sufficient stock of plots to allow for that interweaving of many actions into one which is the characteristic of the Romantic Drama of Marlowe and his compeers.

That Painter was the main source of plot for the dramatists before Marlowe, we have explicit evidence. Of the very few extant dramas before Marlowe, Appius and Virginia, Tancred and Gismunda, and Cyrus and Panthea are derived from Painter.23 We have also references in contemporary literature showing the great impression made by Painter’s book on the opponents of the stage. In 1572 E. Dering, in the Epistle prefixed to A briefe Instruction, says: “To this purpose we have gotten our Songs and Sonnets, our Palaces of Pleasure, our unchaste Fables and Tragedies, and such like sorceries.... xxxi O that there were among us some zealous Ephesian, that books of so great vanity might be burned up.” As early as 1579 Gosson began in his School of Abuse the crusade against stage-plays, which culminated in Prynne’s Histriomastix. He was answered by Lodge in his Defence of Stage Plays. Gosson demurred to Lodge in 1580 with his Playes Confuted in Five Actions, and in this he expressly mentions Painter’s Palace of Pleasure among the “bawdie comedies” that had been “ransacked” to supply the plots of plays. Unfortunately very few even of the titles of these early plays are extant: they probably only existed as prompt-books for stage-managers, and were not of sufficient literary value to be printed when the marriage of Drama and Literature occurred with Marlowe.

But we have one convincing proof of the predominating influence of the plots of Painter and his imitators on the Elizabethan Drama. Shakespeare’s works in the first folio, and the editions derived from it, are, as is well known, divided into three parts—Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. The division is founded on a right instinct, and applies to the whole Elizabethan Drama.24 Putting aside the Histories, which derive from Holinshed, North, and the other historians, the dramatis personæ of the Tragedies and Comedies are, in nineteen cases out of twenty, provided with Italian names, and the scene is placed in Italy. It had become a regular convention with the Elizabethans to give an Italian habitation and name to the whole of their dramas. This convention must have arisen in the pre-Marlowe days, and there is no other reason to be given for it but the fact that the majority of plots are taken from the “Palace of Pleasure” or its followers. A striking instance is mentioned by Charles Lamb of the tyranny of this convention. In the first draught of his Every Man in his Humour Ben Jonson gave Italian names to all his dramatis personæ. Mistress Kitely appeared as Biancha, Master Stephen as Stephano, and even the immortal Captain Bobabil as Bobadilla. Imagine Dame Quickly as Putana, and Sir John as Corporoso, and we can see what a profound xxxii influence such a seemingly superficial thing as the names of the dramatis personæ has had on the Elizabethan Drama through the influence of Painter and his men.

But the effect of this Italianisation of the Elizabethan Drama due to Painter goes far deeper than mere externalities. It has been said that after Lamb’s sign-post criticisms, and we may add, after Mr. Swinburne’s dithyrambs, it is easy enough to discover the Elizabethan dramatists over again. But is there not the danger that we may discover too much in them? However we may explain the fact, it remains true that outside Shakespeare none of the Elizabethans has really reached the heart of the nation. There is not a single Elizabethan drama, always of course with the exception of Shakespeare’s, which belongs to English literature in the sense in which Samson Agonistes, Absalom and Achitophel, Gulliver’s Travels, The Rape of the Lock, Tom Jones, She Stoops to Conquer, The School for Scandal, belong to it. The dramas have not that direct appeal to us which the works I have mentioned have continued to exercise after the generation for whom they were written has passed away. To an inner circle of students, to the 500 or so who really care for English literature, the Elizabethan dramas may appeal with a power greater than any of these literary products I have mentioned. We recognise in them a wealth of imaginative power, an ease in dealing with the higher issues of life, which is not shown even in those masterpieces. But the fact remains, and remains to be explained, that the Elizabethans do not appeal to the half a million or so among English folk who are capable of being touched at all by literature, who respond to the later masterpieces, and cannot be brought into rapport with the earlier masters. Why is this?

Partly, I think, because owing to the Italianisation of the Elizabethan Drama the figures whom the dramatists drew are unreal, and live in an unreal world. They are neither Englishmen nor Italians, nor even Italianate Englishmen. I can only think of four tragedies in the whole range of the Elizabethan drama where the characters are English: Wilkins’ Miseries of Enforced Marriage, and A Yorkshire Tragedy, both founded on a recent cause celèbre of one Calverly, who was executed 5 August xxxiii 1605; Arden of Faversham, also founded on a cause celèbre of the reign of Edward VI.; and Heywood’s Woman Killed by Kindness. These are, so far as I remember, the only English tragedies out of some hundred and fifty extant dramas deserving that name.25 As a result of all this, the impression of English life which we get from the Elizabethan Drama is almost entirely derived from the comedies, or rather five-act farces, which alone appear to hold the mirror up to English nature. Judged by the drama, English men and English women under good Queen Bess would seem incapable of deep emotion and lofty endeavour. We know this to be untrue, but that the fact appears to be so is due to the Italianising of the more serious drama due to Painter and his school.

In fact the Italian drapery of the Elizabethan Drama disguises from us the significant light it throws upon the social history of the time. Plot can be borrowed from abroad, but characterisation must be drawn from observation of men and women around the dramatist. Whence, then comes the problem, did Webster and the rest derive their portraits of their White Devils, those imperious women who had broken free from all the conventional bonds? At first sight it might seem impossible for the gay roysterers of Alsatia to have come into personal contact with such lofty dames. But the dramatists, though Bohemians, were mostly of gentle birth, or at any rate were from the Universities, and had come in contact with the best blood of England. It is clear too from their dedications that the young noblemen of England admitted them to familiar intercourse with their families, which would include many of the grande dames of Elizabeth’s Court. Elizabeth’s own character, recent revelations about Mistress Fitton, Shakespeare’s relations with his Dark Lady, all prepare for the belief that the Elizabethan dramatists had sufficient material from their own observation to fill up the outlines given by the Italian novelists.26 The Great Oyer of Poisoning—the case of Sir Thomas xxxiv Overbury and the Somersets—in James the First’s reign could vie with any Italian tale of lust and cruelty.

Thus in some sort the Romantic Drama was an extraneous product in English literature. Even the magnificent medium in which it is composed, the decasyllabic blank verse which the genius of Marlowe adapted to the needs of the drama, is ultimately due to the Italian Trissino, and has never kept a firm hold on English poetry. Thus both the formal elements of the Drama, plot and verse, were importations from Italy. But style and characterisation were both English of the English, and after all is said it is in style and characterisation that the greatness of the Elizabethan Drama consists. It must however be repeated that in its highest flights in the tragedies, a sense of unreality is produced by the pouring of English metal into Italian moulds.

It cannot be said that even Shakespeare escapes altogether from the ill effects of this Italianisation of all the externalities of the drama. It might plausibly be urged that by pushing unreality to its extreme you get idealisation. A still more forcible objection is that the only English play of Shakespeare’s, apart from his histories, is the one that leaves the least vivid impression on us, The Merry Wives of Windsor. But one cannot help feeling regret that the great master did not express more directly in his immortal verse the finer issues and deeper passions of the men and women around him. Charles Lamb, who seems to have said all that is worth saying about the dramatists in the dozen pages or so to which his notes extend, has also expressed his regret. “I am sometimes jealous,” he says, “that Shakespere laid so few of his scenes at home.” But every art has it conventions, and by the time Shakespeare began to write it was a convention of English drama that the scene of its most serious productions should be laid abroad. The convention was indeed a necessary one, for there did not exist in English any other store of plots but that offered by the inexhaustible treasury of the Italian Novellieri.

Having mentioned Shakespeare, it seems desirable to make an exception in his case,27 and discuss briefly the use he made of xxxv Painter’s book and its influence on his work. On the young Shakespeare it seems to have had very great influence indeed. The second heir of his invention, The Rape of Lucrece, is from Painter. So too is Romeo and Juliet,28 his earliest tragedy, and All’s Well, which under the title Love’s Labour Won, was his second comedy, is Painter’s Giletta of Narbonne (i. 38) from Bandello.29 I suspect too that there are two plays associated with Shakespeare’s name which contain only rough drafts left unfinished in his youthful period, and finished by another writer. At any rate it is a tolerably easy task to eliminate the Shakespearian parts of Timon of Athens and Edward III., by ascertaining those portions which are directly due to Painter.30 In this early period indeed it is somewhat remarkable with what closeness he followed his model. Thus some gushing critics have pointed out the subtle significance of making Romeo at first in love with Rosalind before he meets with Juliet. If it is a subtlety, it is Bandello’s, not Shakespeare’s. Again, others have attempted to defend the indefensible age of Juliet at fourteen years old, by remarking on the precocity of Italian maidens. As a matter of fact Bandello makes her eighteen years old. It is banalities like these that cause one sometimes to feel tempted to turn and rend the criticasters by some violent outburst against Shakespeare himself. There is indeed a tradition, that Matthew Arnold had things to say about Shakespeare which he dared not utter, because the British public would not stand them. But the British public has stood some very severe things about the Bible, which is even yet reckoned of higher sanctity than Shakespeare. And certainly there is as much cant about Shakespeare to be cleared away as about the Bible. However this is scarcely the place to do it. It is clear enough, however, xxxvi from his usage of Painter, that Shakespeare was no more original in plot than any of his fellows, and it is only the unwise and rash who could ask for originality in plot from a dramatic artist.

But if the use of Italian novelle as the basis of plots was an evil that has given an air of unreality and extraneousness to the whole of Elizabethan Tragedy, it was, as we must repeat, a necessary evil. Suppose Painter’s work and those that followed it not to have appeared, where would the dramatists have found their plots? There was nothing in English literature to have given them plot-material, and little signs that such a set of tales could be derived from the tragedies going on in daily life. But for Painter and his school the Elizabethan Drama would have been mainly historical, and its tragedies would have been either vamped-up versions of classical tales or adaptations of contemporary causes celèbres.

And so we have achieved the task set before us in this Introduction to Painter’s tales. We have given the previous history of the genre of literature to which they belong, and mentioned the chief novellieri who were their original authors. We have given some account of Painter’s life and the circumstances under which his book appeared, and the style in which he translates. We have seen how his book was greeted on its first appearance by the adherents of the New Learning and by the opponents of the stage. The many followers in the wake of Painter have been enumerated, and some account given of their works. It has been shown how great was the influence of the whole school on the Elizabethan dramatists, and even on the greatest master among them. And having touched upon all these points, we have perhaps sufficiently introduced reader and author, who may now be left to make further acquaintance with one another.

xxxviiWilliam Painter was, probably, descended from some branch of the family of that name which resided in Kent. Except a few official dates there is little else of his personal history known. Neither the time nor place of his birth has been discovered. All the heralds in their Visitations are uniformly content with making him the root of the pedigree.31 His liberal education is, in part, a testimony of the respectability of his family, and, it may be observed, he was enabled to make purchases of landed property in Kent, but whether from an hereditary fortune is uncertain.

The materials for his life are so scanty, that a chronological notice of his Writings may be admitted, without being deemed to interrupt a narrative, of which it must form the principal contents.

He himself furnishes us with a circumstance,32 from whence we may fix a date of some importance in ascertaining both the time of the publication and of his own appearance as an author. He translated from the Latin of Nicholas Moffan, (a soldier serving under Charles the Fifth, and taken prisoner by the Turks)33 the relation of the Murder which Sultan Solyman caused to be xxxviii perpetrated on his eldest Son Mustapha.34 This was first dedicated to Sir William Cobham Knight, afterwards Lord Cobham, Warden of the Cinque Ports; and it is material to remark, that that nobleman succeeded to the title Sept. the 29th, 1558;35 and from the author being a prisoner until Sept. 1555, it is not likely that the Translation was finished earlier than circa 1557-8.

In 1560 the learned William Fulke, D.D. attacked some inconsistent, though popular, opinions, in a small Latin tract called “Antiprognosticon contra invtiles astrologorvm prædictiones Nostrodami, &c.” and at the back of the title are Verses,36 by friends of the author, the first being entitled “Gulielmi Painteri ludimagistri Seuenochensis Tetrasticon.” This has been considered by Tanner as our author,37 nor does there appear any reason for attempting to controvert that opinion; and a translation of Fulke’s Tract also seems to identify our author with the master of Sevenoaks School. The title is “Antiprognosticon, that is to saye, an Inuectiue agaynst the vayne and unprofitable predictions of the Astrologians as Nostrodame, &c. Translated out of Latine into Englishe. Whereunto is added by the author a shorte Treatise in Englyshe as well for the utter subversion of that fained arte, as well for the better understandynge of the common people, unto whom the fyrst labour semeth not sufficient. Habet & musca splenem & formice sua bilis inest. 1560” 12mo. At the back of the title is a sonnet by Henry Bennet: followed in the next page by Painter’s Address. On the reverse of this last page is a prose address “to his louyng frende W. F.” dated “From Seuenoke XXII of Octobre,” and signed “Your familiar frende William Paynter.”38

xxxix By the regulations of the school, as grammar-master, he must have been a bachelor of arts, and approved by the Archbishop of Canterbury, and to the appointment was attached a house and salary of £50 per annum.39

Of the appointment to the School I have not been able to obtain any particulars. That situation40 was probably left for one under government, of less labour, as he was appointed by letters patent of the 9th of Feb. in the 2d of Eliz. (1560-1) to succeed John Rogers, deceased, as Clerk of the Ordinance in the Tower, with the official stipend of eightpence per diem, which place he retained during life.

In 1562 there was a license obtained by William Jones to print “The Cytie of Cyvelite, translated into Englesshe by william paynter.” Probably this was intended for the present work, and entered in the Stationers Register as soon as the translation was commenced, to secure an undoubted copy-right to the Publisher. Neither of the stories bear such a title, nor contain incidents in character with it. The interlocutory mode of delivery, after the manner of some of the originals, might have been at first intended, and of the conversation introducing or ending some of those taken from the collection of the Queen of Navarre, a part is even now, though incongruously, retained.41 By rejecting the gallant speeches of the courtiers and sprightly replies of the ladies, and making them unconnected stories, the idea of civility was no longer appropriate, and therefore gave place to a title equally alliterative in the adoption of the Palace of Pleasure.

Under this conjecture Painter was three years perfecting the xl Translation of the first volume of the Palace of Pleasure. He subscribes the dedicatory Epistle “nere the Tower of London the first of Januarie 1566,” using the new style, a fashion recently imported from France.42 It must be read as 1565-6 to explain a passage in another Epistle before the second volume, where he speaks of his histories “parte whereof, two yeares past (almost) wer made commune in a former boke,” concluding “from my poore house besides the Toure of London, the fourthe of November, 1567.” The two volumes were afterwards enlarged with additional novels, as will be described under a future head, and with the completion of this task ends all knowledge of his literary productions.

It no where appears in the Palace of Pleasure that Painter either travelled for information, or experienced, like many a genius of that age, the inclination to roam expressed by his contemporary, Churchyard,

“Of running leather were his shues, his feete no where could reste.”43

Had he visited the Continent, it is probable, that in the course of translating so many novels, abounding with foreign manners and scenery, there would have been some observation or allusion to vouch his knowledge of the faithfulness of the representation, as, in a few instances, he has introduced events common in our own history.

He probably escaped the military fury of the age by being appointed “Clerk to the great Ordinance,” contentedly hearing the loud peals upon days of revelry, without wishing to adventure further in “a game,” which, “were subjects wise, kings would not play at.” In the possession of some competence he might prudently adjust his pursuits, out of office, to the rational and not unimportant indulgence of literature,44 seeking in the retirement xli of the study, of the vales of Kent, and of domestic society, that equanimity of the passions and happiness which must ever flow from rational amusement, from contracted desires, and acts of virtue; and which the successive demands for his favourite work might serve to cheer and enliven.

As the founder of the family45 his money must be presumed to have been gained by himself, and not acquired by descent. It would be pleasing to believe some part of it to have been derived from the labours of his pen. But his productions were not of sufficient magnitude to command it, although he must rank as one of the first writers who introduced novels into our language, since so widely lucrative to—printers. Yet less could there accrue a saving from his office to enable him to complete the purchases of land made at Gillingham, co. Kent.

At what period he married cannot be stated. His wife was Dorothy Bonham of Cowling, born about the year 1537, and their six children were all nearly adults, and one married, at the time of his death in 1594. We may therefore conclude that event could not be later than 1565; and if he obtained any portion with his wife the same date allows of a disposition of it as now required.

It is certain that he purchased of Thomas and Christopher Webb the manor of East-Court in the parish of Gillingham, where his son Anthony P. resided during his father’s lifetime. He also purchased of Christopher Sampson the manor of Twidall in the same parish with its appurtenances, and a fine was levied for that purpose xlii in Easter Term 16 Eliz. Both the manors remained in the family, and passed by direct line from the above named Anthony, through William and Allington, his son and grandson, to his great grandson Robert, who resided at Westerham, in the same county, and obtained an Act of Parliament, 7 Geo. I. “to enable him to sell the manors of Twydal and East-Court.”46

xliii Not any part of the real Estate was affected by the will of William Painter, who appears, from its being nuncupative, to have deferred making it, until a speedy dissolution was expected. It is as follows:

“In the name of God, Amen. The nineteenth day of February in the Year of our Lord God one thousand five hundred ninety four, in the seven and thirtieth year of the reign of our Sovereign Lady Elizabeth, &c. William Painter then Clerk of her Maj. Great Ordinance of the Tower of London, being of perfect mind and memory, declared and enterred his mind meaning and last Will and Testament noncupative, by word of mouth in effect as followeth, viz. Being then very sick and asked by his wife who should pay his son in law John Hornbie the portion which was promised him with his wife in marriage, and who should pay to his daughter Anne Painter her portion, and to the others his children which had nothing;47 and whether his said wife should pay them the same, the said William Painter answered, Yea. And being further asked whether he would give and bequeath unto his said wife all his said goods to pay them as he in former times used to say he would, to whom he answered also, yea. In the presence of William Pettila, John Pennington, and Edward Songer. Anon after in the same day confirming the premises; the said William Painter being very sick, yet of perfect memory, William Raynolds asking the aforesaid Mr. Painter whether he had taken order for the disposing of his Goods to his wife and children, and whether he had put all in his wives hands to deal and dispose of and to pay his son Hornby his portion,48 and whether he would make his said wife to be his whole Executrix, or to that effect, to whose demand the said Testator Mr. William Painter then manifesting his will and true meaning therein willingly answered, yea, in the presence of William Raynolds, John Hornbie and Edward Songer.”48

He probably died immediately after the date of the will. Among the quarterly payments at the ordinance office at Christmas 1594 is entered to “Mr. Painter Clerke of thõdiñce xvijlb, xvs.” and upon Lady Day or New Year’s Day 1595. “To Willm̅ Painter and to Sr. Stephen Ridleston49 Clarke of Thordñce for the xliv like quarter also warranted xvijlb. xvs.” He was buried in London.50 After his death the widow retired to Gillingham, where she died Oct. 19th 1617. Æt. 80, and where she was buried.51

[For some additional points throwing light on the way in which Painter gained his fortune, see Appendix. Collier (Extr. Stat. Reg. ii. 107), attributes to Painter A moorning Ditti vpon the Deceas of Henry Earle of Arundel, which appeared in 1579, and was signed ‘Guil. P. G.’ [= Gulielmus Painter, Gent.].—J. J.]

xlvIn the following section, text in boldface was originally printed in blackletter type.

Of the first volume of THE PALACE OF PLEASURE there were three editions, but of the second only two are known. Each of these, all uncommonly fair and perfect, through the liberal indulgence of their respective owners, are now before me; a combination which has scarcely been seen by any collector, however distinguished for ardour of pursuit and extensiveness of research, since the age of Q. Elizabeth. Their rarity in a perfect state may render an accurate description, though lengthened by minuteness, of some value to the bibliographer. The account of them will be given in their chronological order.

The Palace of Pleasure | Beautified, adorned and | well furnished with Plea- | saunt Histories and excellent | Nouells, selected out of | diuers good and commen- | dable authors. | ¶ By William Painter Clarke of the | Ordinaunce and Armarie. | [Wood-cut of a Bear and ragged Staff, the crest of Ambrose Earl of Warwick, central of a garter, whereon is the usual motto | HONI: SOIT: QVI: MAL: Y: PENSE. | 1566. | JMPRINTED AT—London, by Henry Denham, | for Richard Tottell and William Iones.52—4to. Extends to sig. Nnnij. besides introduction, and is folded in fours.

This title is within a narrow fancy metal border, and on the back of the leaf are the Arms of the Earl of Warwick, which fill the page. With signature * 2 commences the dedication, and at ¶ 2 is “a recapitulacion or briefe rehersal of the Arguments of euery Nouell, with the places noted, in what author euery of the same or the effect be reade and contayned.” These articles occupy four leaues each, and five more occupy the address “to the reader,” xlvi followed by the names of the Authors from whom the “nouels be selected;” making the whole introduction, with title, 14 leaves.

The nouels being lx. in number, conclude with folio 345, but there are only 289 leaves, as a castration appears of 56.53 On the reverse of the last folio are “faultes escaped in the printing;” and besides those corrected, there are “other faultes [that] by small aduise and lesse payne may by waying the discourse be easely amended or lightly passed ouer.” A distinct leaf has the following colophon:

Imprinted at Lon | don, by Henry Denham, | for Richard Tottell and | William Jones | Anno Domini. 1566 | Ianuarij 26. |These bookes are to be solde at the long shoppe | at the Weast ende of Paules.

This volume is rarely discovered perfect. The above was purchased at the late sale of Col. Stanley’s library for 30l. by Sir Mark Masterman Sykes, Bt.

The second Tome | of the Palace of Pleasure | conteyning manifolde store of goodly | Histories, Tragicall matters and | other Morall argument, | very requisite for de- | light & profit. |Chosen and selected out of diuers good and commen- | dable Authors. | By William Painter, Clarke of the | Ordinance and Armarie. | ANNO. 1567. | Imprinted at London, in Pater Noster Rowe, by Henrie | Bynneman, for Nicholas | England.54 4to. Extends, without introduction, to signature P. P. P. P. p. iiij. and is folded in fours.

A broad metal border, of fancy pattern, adorns the title page. At signature a. ij. begins the Epistle to Sir George Howard, which the author subscribes from his “poore house besides the Toure of London, the fourthe of Nouember 1567:” and that is xlvii followed by a summary of the contents and authorities, making, with the title, 10 leaves. There are xxxiiij novels, and they end at fo. 426. Two leaves in continuation have “the conclusion,” with “divers faultes escaped in printyng,” and on the reverse of the first is the printer’s colophon.

Imprinted at London | by Henry Bynneman | for Nicholas Englande | ANNO M.D.LXVII. | Nouembris 8.

A copy of this volume was lately in the possession of Messrs. Arch, of Cornhill, Booksellers, with a genuine title, though differently arranged from the above, and varied in the spelling.55 When compared, some unimportant alterations were found, as a few inverted commas on the margin of one of the pages in the last sheet, with the correction of a fault in printing more in one copy than the other, though the same edition.56

The Pallace | of Pleasure Beautified, | adorned and wel furnished with | Pleasaunt Historyes and excellent | Nouelles, selected out of diuers | good and commendable Authours. | ¶ By William Painter Clarke | of the Ordinaunce and | Armarie. | 1569. | Jmprinted at London in | Fletestreate neare to S. Dunstones | Church by Thomas Marshe.—4to. Extends to K k. viij, & is folded in eights.

xlviii The title is in the compartment frequently used by Marsh, having the stationers’ arms at the top, his own initials at the bottom, and pedestals of a Satyr and Diana, surmounted with flowers and snakes, on the sides. It is a reprint of the first volume without alteration, except closer types. The introduction concludes on the recto of the eleventh leaf, and on the reverse of fo. 264 is the colophon. Jmprinted at London in Flete | streate neare unto Sainct Dunstones | Churche by Thomas Marshe | Anno Domini. 1569.57

THE PALACE | of Pleasure Beautified | adorned and well furnished | with pleasaunt Histories and | excellent Nouels, selected out | of diuers good and commendable Authors. By William Painter Clarke | of the Ordinaunce | and Armarie. | Eftsones perused corrected | and augmented. | 1575. | Imprinted at London | by Thomas Marshe.—4to. Extends to signature O o, iiij. and is folded in eights.58

Title in same compartment as the last. The introduction is given in nine leaves, and the novels commence the folio, and end at 279. The arguments of every novel, transposed from the beginning, continue for three leaves to reverse of O o iiij, having for colophon,

Imprinted at London by | Thomas Marshe.

Seven novels were added to the former number, and the language improved.

xlixTHE SECOND | Tome of the Palace of | Pleasure contayning store of goodlye | Histories, Tragical matters, & other | Morall argumentes, very requi- | site for delight and | profyte. | Chosē and selected out | of diuers good and commendable au- | thors, and now once agayn correc- | ted and encreased. | By Wiliam Painter, Clerke of the | Ordinance and Armarie. | Imprinted at London | In Fleatstrete by Thomas | MARSHE.—4to. Has signature Z z 4, and is folded in eights.

Title in the compartment last described. The introduction has seven leaves, and the “conclusion” is at fo. 360.59 The summary of nouels, which stand as part of the introduction in the former edition, follows, making four leaves after discontinuing the folio. There is no printer’s colophon, and the type throughout is smaller than any used before. The translator added one historic tale, and made material alterations in the text.